What do you think?

Rate this book

154 pages, Paperback

First published October 1, 2009

But as you can see this cover states; Ru a novel by Kim Thuy. For me the ideal novel has development, a plot and conclusion. This slim volume doesn't. These are literary fragments beautifully written and no doubt at least partly autobiographical but they are still fragments. My interest was high at the start but went downhill faster than an Olympic gold medal skier.

But as you can see this cover states; Ru a novel by Kim Thuy. For me the ideal novel has development, a plot and conclusion. This slim volume doesn't. These are literary fragments beautifully written and no doubt at least partly autobiographical but they are still fragments. My interest was high at the start but went downhill faster than an Olympic gold medal skier.I like the red leather of the sofa in the cigar lounge where I dare to strip naked in front of friends and sometimes strangers, without their knowledge. I recount bits of my past as if they were anecdotes or comedy routines or amusing tales from far-off lands featuring exotic landscapes, odd sound effects and exaggerated characterizations.

Absolutely no one will know the true story of the pink bracelet once the acrylic has decomposed into dust, once the years have accumulated in the thousands, in hundreds of strata, because after only thirty years I already recognize our old selves only through fragments, through scars, through glimmers of light.

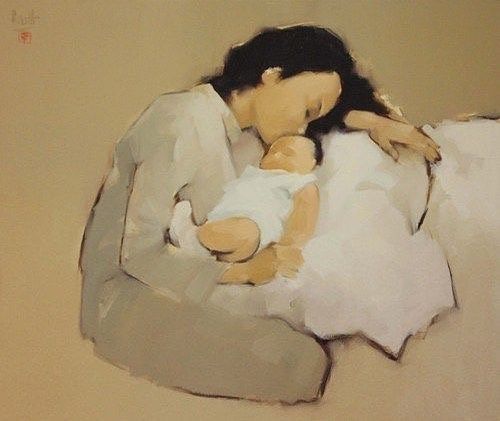

I had completely forgotten that gesture, which I’d performed a thousand times when I was small. I’d forgotten that love comes from the head and not the heart. Of the entire body, only the head matters. Merely touching the head of a Vietnamese person insults not just him but his entire family tree.

...

When I meet young girls in Montreal or elsewhere who injure their bodies intentionally, deliberately, who want permanent scars to be drawn on their skin, I can’t help secretly wishing they could meet other young girls whose permanent scars are so deep they’re invisible to the naked eye.