The Táin Bó Cúailnge is known as maybe the greatest epic in Irish heroic age mythology. It’s been called the Irish Iliad, and is considered Ireland’s national epic. It deserves all these accolades, and then some. This is a furious, bloody, grand heroic saga, a celebration of the Ulaid people, one of them in particular, the pinnacle of the Ulster cycle, and an all around intensely inspired legend that floored me with its inventiveness and imagination.

It is a myth that was carried through the ages orally and then written down in a few different recensions, starting in the eighth century, until its final written form sometime in the 12th. It has all the ancient charm and style and mystical otherworldly beauty of the medieval Irish sagas. In the form it appears in here it is breathtaking. The saga is told in a blend of prose, verse, and vivid, grand motifs that I have seen nowhere else, except in the other old Irish tales.

Because this is a story that is part of a larger tradition of myths, many of the canonical rulers and warriors and people from the Ulster cycle are here, including Fergus Mac Roich, former king of the Ulaid, now in exile at the court of the rulers of Connacht in the west, king Ailill and queen Medb. The story that explains how he ended up in their army is found elsewhere in the Ulster cycle, in a story called “The Exile of the Sons of Uisliu.” Also here are various legendary warriors who appear in other sagas, too numerous to mention by name, and Conchobar Mac Nessa, current king of the Ulaid, and then the seemingly invincible Cu Chulainn. There is quite a bit of necessary backstory to the Tain, and most of it is told in other Irish sagas and tales. The translator’s notes do a great job summarizing the relevant ones, but many of the most important ones can be found in Early Irish Myths and Sagas.

After Ailill and Medb get into a competition about who has the better collection of treasures, and Medb’s is found comparatively lacking because of Ailill’s prize bull, they decide to go raiding for a massive and magnificent mystical bull in Cuailnge, in the Ulaid region.

The Ulaid men are, at this time, cursed with labor pains, as detailed in the myth “The Labor Pains of the Ulaid”. In this story, Macha, the euhemerized Irish horse goddess, outraged after no one steps forward to help her when she is made to race a chariot on foot and goes into labor at the finish line, curses the men of Ulster for nine generations to experience labor pains and to become as weak as a woman in labor. So the Ulaid are helpless to defend against the armies of Connacht, and eventually the armies of the rest of Ireland. The only Ulaid man unaffected by this curse is the indomitable, peerless hero Cu Chulainn.

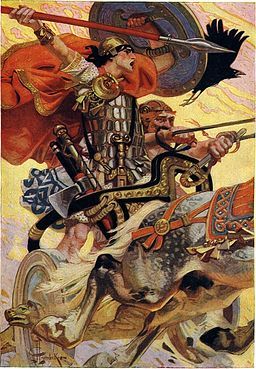

Thus begins Cu Chulainn’s brilliant one-man counterstrike against all the armies of Ireland, holding them off from pushing deeper into Ulaid territory, avenging against their murder and rape of the Ulaid people, and the theft of their cattle.

For pages and pages the story is an evocative symphony of guerrilla warfare and brute strength and immaculate fighting and weapon mastery and graceful yet vicious Celtic combat in all its gory, extraordinary, poetic glory. Cu Chulainn is an endearing but formidable hero, a youth whose beardless face and age make veteran warriors underestimate him, to their own misfortune. There is much more to the story than these battles and warfare, but the continuous thread of combat and the theme of a single heroic warrior against thousands is prevalent.

The adventures and exploits of Cu Chulainn’s childhood are related by storytellers among the Connacht army, warning Ailill and Medb of who they are up against. Through these small tales we see a natural born vanquisher, inclined toward heroism and daring deeds from the beginning, taking on numerous foes far beyond his size and performing feats thought impossible. Despite this, the armies go hard against Cu Chulainn. He is only one man, and they are legion.

The body count of those he slays is incalculable. Despite his fearless warrior ethic, despite his sureness of his capabilities and his power, he is a modest, fair, and balanced man. A motif that appeared in other Irish sagas is repeated here. Each time Cu Chulainn’s camp is approached by a warrior to who seeks to face him in single combat, his charioteer Laeg describes, in illustrious detail and heroic fashion the man approaching, and Cu Chulainn explains who it is, also in a manner befitting the wild spirit of warriors, what each is known for. And they face each other. And Cu Chulainn always destroys his opponent.

This same motif appears toward the end, after the curse has left the Ulaid and the kings and heroes of the Ulaid come together in a united front against all the armies of Ireland. Medb sends a scout out to see what is going on, and the scout reports back what he sees, often surreal and poetic visions, or beautifully decorated powerful kings and warriors and armies, and Fergus explains who or what he is seeing.

Also in keeping with tradition from Irish myth is the place-name lore, known formally as Dindsenchas. Every few pages it seems there is a brief aside or tiny vignette to explain how some ancient place in Ireland got its name, whether town or region or river or geographical feature, often from someone being killed there or some (pseudo)historically significant event of legendary proportions occurring nearby.

Cu Chulainn is visited, aided, and impaired by Tuatha de Danan in his struggle for supremacy over the Irish armies. Eventually he is helped by his fellow Ulaidmen as they begin to recover from the curse, some proving to be nearly as formidable as Cu Chulainn himself. So too does his father appear, the god Lugh, who heals his son over many days so that he may fight again. While is recovering, some of his fellow Ulaidmen attempt to fight off Medb’s army, and are crushed. Cu Chulainn’s vengeance is one of the most Herculean feats I’ve seen in an epic. But then again, many of the things he does here stand toward the top of the tower of heroic exploits I’ve witnessed in epics and sagas.

He is eventually laid low by grueling four day combat with his foster brother, Fer Diad, his final adversary in single-combat, a battle that is moving and timeless.

The fight starts enthusiastically and they recite poetry at one another, reminisce about their days together, and every night sees them retreat wounded, first close and friendly, but each night growing further apart, more injured, less friendly, until their final tragic conflict.

There’s a point in the story where Ailill discovers Fergus is sleeping with Medb. In a strange confrontation, Ailill asks Fergus to play fidchell with him, an ancient game thought to be sort of like chess, and they begin speaking to each other in a somewhat metaphorical, verse-like style, called roscada.

According to the translator, these parts are written in a distinct way in the original manuscripts, but they are hard to make sense of. This method of speaking recurs throughout the Tain when things reach a fevered pitch and the tone becomes dramatic, vibrant, almost musical. And although they resemble poetry, they are distinct from the parts in which the characters clearly speak in verse, with more traditional and understandable poetic structure. I don’t know if anyone has the answers to why these parts were written as they were, but they appear to be an ancient element of the language or literature whose purpose and understanding has been somewhat lost over the ages.

What’s most interesting to me about these roscada, aside from the engrossing aspect they present to the storytelling and how they heighten the sense of art and drama, is something the translator points out in the notes.

The Ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote about early encounters with the Gauls (early Celts), and he described their manner of speaking to one another in exactly this way — taking on the form of riddle or metaphor, where the words might have multiple meanings, and those meanings would only be clear to those speaking, all but indecipherable to an outside listener. That this characteristic of the Celts is corroborated by historical evidence and mythological literature is satisfying in a way I can’t quite give words to. It lends an extra dimension to the myths, as though they have life in them that is distant and far removed from our experience, but very true to the world from which they come.

The Tain is full of stuff like this, captivating, magical power, rich layers of meaning and imagery and activity bleeding through history and through morphing shapes of language that contort our interpretations for better or worse. Its excellence as a story of monumental and legendary events and figures is unquestionable. It’s the kind of epic that demands many rereads and long pauses to take in all its wonders. Many times I reread entire passages or pages of the Tain because of their immense beauty or power or oddness or because the way with words was so dominating it demanded repeated visits.