What do you think?

Rate this book

One of Publishers Weekly’s Top Ten Spring 2013 Science Books

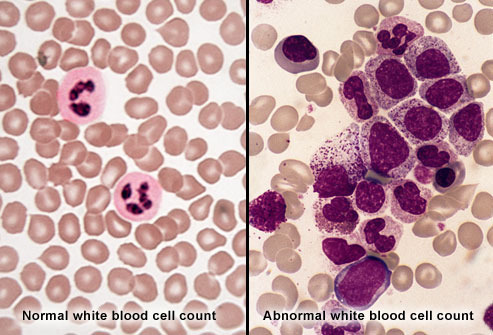

Philadelphia, 1959: A scientist scrutinizing a single human cell under a microscope detects a missing piece of DNA. That scientist, David Hungerford, had no way of knowing that he had stumbled upon the starting point of modern cancer research—the Philadelphia chromosome. This book charts not only that landmark discovery, but also—for the first time, all in one place—the full sequence of scientific and medical discoveries that brought about the first-ever successful treatment of a lethal cancer at the genetic level.

The significance of this mutant chromosome would take more than three decades to unravel; in 1990, it was recognized as the sole cause of a deadly blood cancer, chronic myeloid leukemia, or CML. This dramatic discovery launched a race involving doctors and researchers around the world, who recognized that in principle it might be possible to target CML at its genetic source.

Science journalist Jessica Wapner brings extensive original reporting to this book, including interviews with more than thirty-five people with a direct role in this story. Wapner reconstructs more than forty years of crucial breakthroughs, clearly explains the science behind them, and pays tribute to the dozens of researchers, doctors, and patients whose curiosity and determination restored the promise of a future to the more than 70,000 people worldwide who are diagnosed with CML each year. Chief among them is researcher and oncologist Dr. Brian Druker, whose dedication to his patients fueled his quest to do everything within his power to save them.

The Philadelphia Chromosome helps us to fully understand and appreciate just how pathbreaking, hard-won, and consequential are the achievements it recounts—and to understand the principles behind much of today’s most important cancer research, as doctors and scientists race to uncover and treat the genetic roots of a wide range of cancers.

320 pages, Hardcover

First published May 1, 2013

“Until we stumbled over this Philadelphia chromosome, there was really no evidence that cancer might be due to genetic change,” Nowell, now 79, said decades later. This photograph would become the lasting portrayal of a moment when everything changed for cancer and medicine as a whole. It was the as-yet unrecognized starting point for the modern era of targeting cancer at its root cause.

The genetic basis of cancer was recognised in 1902 by the German zoologist Theodor Boveri, professor of zoology at Munich and later in Würzburg. He discovered a method to generate cells with multiple copies of the centrosome, a structure he discovered and named. He postulated that chromosomes were distinct and transmitted different inheritance factors. He suggested that mutations of the chromosomes could generate a cell with unlimited growth potential which could be passed on to its descendants. He proposed the existence of cell cycle checkpoints, tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes. He speculated that cancers might be caused or promoted by radiation, physical or chemical injuries, or by pathogenic microorganisms.

If the cell is like a house, then identifying src’s product was like pointing to a single part of the house and declaring it important.

If cancer is like a gun, then the kinase is like the finger behind the trigger.

In the hunt for cancer’s underlying mechanism, finding tyrosine was like a tracker finding an animal’s footprint or a broken branch.

Like pieces on a chessboard assembling for checkmate, discoveries and researchers were slowly coming together.

Like an impressionable child, these embryonic cells proved susceptible to the virus outside of the protective shield of the womb.

like a metal detector scanning for gold lost underneath the sand.

It was like moving from the broad strokes of Matisse to the pointillism of Seurat.

It’s like a chef who has used the first knife she bought for cooking school to make ever more complicated dishes; that knife is highly conserved.

like a relay race in which the gene shoots the gun and the kinase is the first runner.

It was like finding the leaky faucet responsible for a persistent dripping noise.

like a mountain climber finding a jutting rock for his next step.

Like a gloved hand fitting perfectly over a mouth to block the next breath, the drug would stop the runaway kinase in its tracks, thereby halting cancer progression.

The amount of phosphotyrosine revealed by the antibody reflected the amount of active kinase. It was like counting the number of sand castles to estimate how many children had been at the beach.

The flag methyl group forced the compound into one immovable arrangement, like a host finalizing the seating for a dinner party.

It was like stopping a car by removing the gas pedal instead of the motor.

The first few days of treatment [Gleevec] were pure hell. Eichner vomited several times a day, often through the night, and the nausea kept him from sleeping.

The STI-571 [Gleevec] experience wasn’t normal. This wasn’t how cancer treatment worked. Patients were supposed to be doubled over in agony, vomiting into waste bins at the side of their bed

corticosteroids (synthetically manufactured versions of hormones produced by our adrenal glands)

further confirming the central role of the Abl

Every attempt was a failure. Finally, the lab contracted the work out, and it soon had its antibody, called 4G10, to phosphorylated tyrosine. From there, Druker could grow the clone, purify it, and experiment with it. But the primary mission had already been accomplished: He had acquired the skill.

The understanding that Matter brought to Zimmermann, isolated in the lab as he was, were enough to sustain his determination to do what Matter was asking them to do.

The persistent pleading from clinicians on the outside gave Matter the confidence to keep fighting. The letter from Druker and all the other voices in support of the drug gave Matter the boost he needed. [...] “Without [everyone] covering my back, I don’t know whether I would have had the stamina to see this through,” Matter said.

As the [clinical] trial finally got under way, Druker remembered Bud Romine’s letter from two years earlier [...] When it was time to start enrolling patients, Druker remembered the bold request.

Every known kinase placed phosphates onto either serine or threonine.

every other kinase known at that time brought phosphate only to either serine or threonine.

The other 900-plus proteins use serine, threonine, or a combination of both.

Of the several kinases known at that point, all stuck their phosphates onto serine or threonine.

When people take interferon, they often develop a fever, chills, and a paralyzing fatigue, like having a flu that lasts for months or even years at a time. The drug can also cause severe depression.

they would remember the decimation wrought by the drug: the tiredness, the persistent flu-like symptoms, the depression.

For the first time, he allowed himself to believe in what was happening. As he watched the tears roll down their cheeks, Druker shed his own as he finally allowed himself to believe what was happening.

Every large company has a kinase inhibitor pipeline: Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca [emphasis mine]