What do you think?

Rate this book

Paperback Bunko

First published November 11, 2012

By editing this series, I stand for the wide dissemination of insightful writings that touch on any aspect related to mathematics. I aim to diminish the gap between mathematics professionals and the general public and to give exposure to a substantial literature that is not currently used systematically in scholarly settings. Along the way, I hope to weaken or even to undermine some of the barriers that stand between mathematics and its pedagogy, history, and philosophy, thus alleviating the strains of hyperspecialization and offering opportunities for connection and collaboration among people involved with different aspects of mathematics.

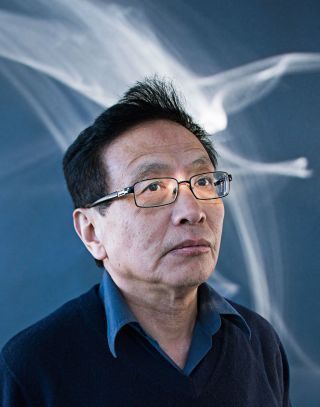

“Sometimes, if it was busy at the store, I helped with the cash register. Even I knew how to make the sandwiches, but I didn’t do it so much.” When Zhang wasn't working, he would go to the library at the University of Kentucky and read journals in algebraic geometry and number theory “For years, I didn’t really keep up my dream in mathematics”, he said.

[Wilkinson:] “You must have been unhappy.”

He shrugged. “My life is not always easy,” he said.

After a few weeks [the readers wrote] “We have completed our study of the paper ‘Bounded Gaps Between Primes’ by Yitang Zhang … The main results are of the first rank. The author has succeeded to prove a landmark theorem in the distribution of prime numbers … Although we studied the arguments very thoroughly, we found it very difficult to spot even the smallest slip … We are very happy to strongly recommend the acceptance of the paper for publication …”