An interesting little book with a misleading title. Appiah by no means explains fully how the moral revolutions of the end of British slavery, the end of Chinese footbinding, and the end of European duelling came about; instead, he shows the role of shifting conceptions of honor in that process.

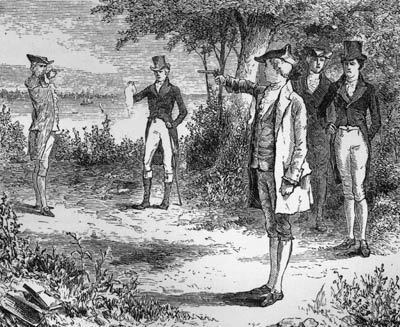

The argument in 3 case studies is that honor can be repurposed from something that encourages violence or oppression to something that ameliorates those things. Honor, for Appiah, is the right to be respected within one's honor community, which can be as small as the English aristocracy or as large as humanity itself. Honor also deals with not just the desire for respect but the desire to be worthy of respect, which means living up to a certain standard. In the case of dueling, honor required maintaining one's standing within the small community of noble males, but it evolved from a way to restrain violence to a destructive practice that was killing off elites and undermining the rule of law. Honor started to be repurposed against dueling because of the rise of bourgeois and working class politics/values, especially the mass press, which mocked dueling as a silly and archaic practice. Also, non-nobles were doing it as well. Both of these things undermined dueling as a marker of elite status, and in a couple of decades the practice virtually disappeared.

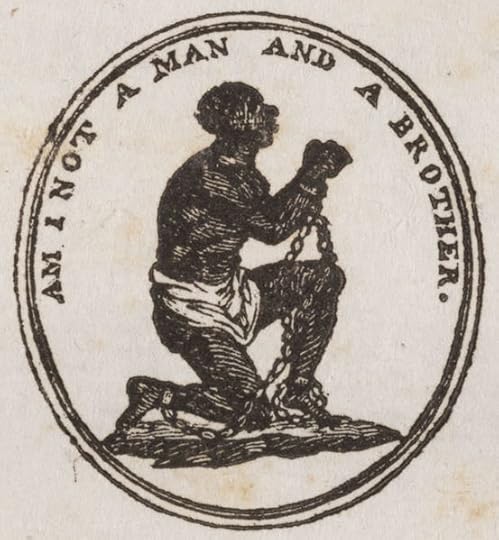

Appiah's argument is even clearer in the case of footbinding, a method both of elite family honor and control of women. As China was being bullied by European powers and JP in the 19th century, some Chinese elites and middle class people started to argue that practices like footbinding brought shame to CHina in the eyes of the world, making them look barbaric and reflecting their overall failure to modernize. As China shifted from monarchy to republic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, footbinding fell out of failure as the country made the first steps toward modernization. Lastly, Appiah shows that the desire for honor and decency in the British middle and upper-middle classes, along with Enlightenment values and changes in Christianity, drove Britain to quite rapidly abolish the slave trade first and slavery second. For the British working class, which turned hard against slavery although not against racism, the driving motivation was to preserve the honor of labor, which they believe slavery degraded by associating the working class with black slaves.

The key to Appiah's argument, which I mostly buy, is that human beings usually don't do what is right just because of abstract moral arguments, a la Kant. They need motivation to do right, and ideally those motives will point in the same direction as morality. Honor can be a powerful motive to pursue the right thing, whether that's restoring one's personal reputation or that of one's class, nation, or creed. This argument appeals to the fact that we are social creatures who care immensely about our personal status in the group and our group's status among other groups. We are not going to get rid of honor, reputation, and other social forces/emotions any time soon, so we need to find ways to change how it operates.

I think this is a wise and valuable argument, but I do have a few small beefs with the book. First, in classic philosopher fashion, APpiah teases the argument out over the course of the book, giving you a little bit here and a little bit there. I kind of prefer the more straightforward argument where the core claims/reasoning are outlined in detail in the intro. Second, I think he goes too far in downplaying the moral shift of the Enlightenment era and of the French, Haitian, American revolutions, all of which shook up the thinking of the time and boosted anti-slavery activism. These small issues aside, this is an interesting book that, at 200 pages, can be processed pretty quickly, and it makes an important contribution to our understanding of why people do the right things, sometimes rapidly transforming longstanding social practices.