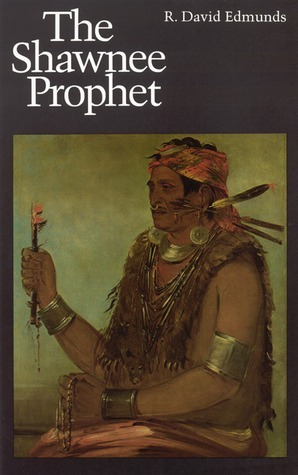

In his biography of the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa, R. David Edmunds convincingly argues that the prophet, not his more famous brother Tecumseh, was the principal leader of the Northwest Indian resistance movement in the early nineteenth century. An alcoholic beggar in his earlier life, Lalewethika (the Prophet's given name) journeyed into the spirit world following near-fatal seizures in 1804-05. There the Master of Life, the philosopher-deity of the eighteenth-century Indian “nativist” movement,” instructed him and other Native Americans to embrace their separate racial identity, live communally with one another, eschew the trappings of white civilization, and renounce the teachings of shamans and sorcerers. The Master's message, as the now-renamed Tenskwatawa (“The Open Door”) conveyed it, proved appealing to the Delawares, Ho-Chunks, Odawas, and other Indian peoples of the Great Lakes region, who were then enduring population decline and great cultural stress. The Prophet recruited hundreds of followers over the next few years, so many that his home base of Greenville (Ohio) became overcrowded and he and his disciples had to build a new one, “Prophetstown,” in western Indiana.

Tenskwatawa's movement was initially a peaceful one – he even traded with nearby Shaker communities – but his followers never gave up their firearms. In 1809, after the controversial Fort Wayne land cession, the men of Prophetstown began to advocate violence against interloping whites and compliant chiefs. Tenskwatawa and his brother Tecumseh began to convert their previously-peaceful religious movement into a military confederacy, and in 1811, when Governor William Harrison moved to destroy Prophetstown, Tenskwatawa sent his young men out to fight, assuring them that his spiritual power would protect them. The ensuing Battle of Tippecanoe was a Pyrrhic victory for Harrison but a fatal blow to Tenskwatawa's prestige. Tecumseh assumed full control of the Northwest Indians' confederacy until his death in battle in late 1813, whereupon the insurgency collapsed. In his later years, Tenskwatawa allied himself with Lewis Cass to promote Shawnee removal to Kansas, where he died in 1836. The Prophet was forgotten for most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries because he did not fit the stereotype of the doomed and noble savage, but his career still raises important questions about the relative usefulness of nonviolent cultural resistance and violent military insurgency. “All unarmed prophets have failed,” Machiavelli famously said, but the armed ones usually don't do very well either.