What do you think?

Rate this book

352 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1911

You suppose that I am a terrorist, now – a destructor of what is, but consider that the true destroyers are they who destroy the spirit of progress and truth, not the avengers who merely kill the bodies of the persecutors of human dignity. Men like me are necessary to make room for self–contained, thinking men like you.

All that means disruption. Better that thousands should suffer than that a people should become a disintegrated mass, helpless like dust in the wind. Obscurantism is better than the light of incendiary torches. The seed germinates in the night. Out of the dark soil springs the perfect plant. But a volcanic eruption is sterile, the ruin of the fertile ground.

In Russia, the land of spectral ideas and disembodied aspirations, many brave minds have turned away at last from the vain and endless conflict to the one great historical fact of the land. They turned to autocracy for the peace of their patriotic conscience as a weary unbeliever, touched by grace, turns to the faith of his fathers for the blessing of spiritual rest. Like other Russians before him, Razumov…felt the touch of grace upon his forehead.Haldin is promptly arrested and hanged without trial. But the reader comes to understand what Razumov, consciously or not, knows immediately; from the moment Haldin appeared in his apartment, his life as he understood it was over. Sheltering Haldin would have drawn him into revolutionary activity, and he’d likely have shared the same fate. But reporting to the authorities, while simultaneously receiving the confidences of Haldin’s friends and associates (who, after Haldin’s execution, believe Razumov to be one of them), also places Razumov under the authorities’ suspicion- and insures that he will serve as their well-placed vassal. Soon enough he travels to Geneva, although it’s not clear whether he is acting as that vassal or as the person Haldin believed him to be. He meets a small group of Russian political exiles living in “little Russia”- the group is led by a Madame Blavatsky-like pseudo-occultist named Eleanora Maximovna de S---- and Peter Ivanovitch, the latter supposedly a great author and brilliant revolutionary. Razumov also meets Haldin’s young sister, Natalia, who is straight out of Dostoevsky: young, beautiful, intelligent, stoic, she believes Razumov is a trusted friend of her brother’s, the last to see him alive, and is the one character in the novel who seems to suggest hope for Russia’s future. “I believe that the future will be merciful to us all”, she tells Razumov. “Revolutionist and reactionary, victim and executioner, betrayer and betrayed, they shall all be pitied together when the light breaks on our dark sky at last.”

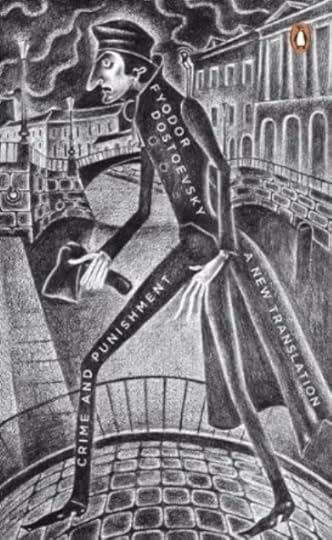

...in a real revolution the best characters do not come to the front. A violent revolution falls into the hands of narrow-minded fanatics and of tyrannical hypocrites at first...such are the chiefs and the leaders. The scrupulous and the just, the noble, humane, and devoted natures...may begin a movement- but it passes away from them. They are not the leaders of a revolution. They are its victims...The book’s introduction calls Under Western Eyes a “response” to Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. It’s true that there are aspects of the book that seem like a satire and homage to Crime and Punishment and Dostoevsky in general- the main character’s name, the insouciance of language and emotion, the unlikely meetings and coincidences, the beautiful and suffering Russian woman who helps the main character find a form of redemption, the themes of political dissidence and revolution (Dostoevsky was once a young revolutionary as well, and nearly died for it), and even the strange quality (intentional, I'll claim, having read enough of Conrad now to see how he varied his style from book to book) that it seems to have been translated from Russian.

That propensity of lifting every problem from the plane of the understandable by means of some sort of mystic expression is very Russian.It almost seems that Conrad needs the fecundity of the South Seas, or of the African Interior, to counterbalance his methods, his approach. Here in the awfully civilized central European capitals we may find him unusually soap-operatic and slightly overdone. Or maybe it is so close to home for the writer, Polish and born in the Ukraine, that every last semi-loyalty must be analyzed and parsed into oblivion.

Speech has been given to us for the purpose of concealing our thoughts...My impression is that it is part of the plan that some details will get lost in the rush, perhaps just mislaid, and some uncertainties will continue further into the mix, as we reach the inner frames of the story. All the better to play when required, on inner storylines when and where the emphasis is needed, rather than as mere introduction. Often this works as a stunning reverberation in a Conrad novel, but sometimes not, as in Under Western Eyes. The risk is a bit like telling a restrained and methodical story of a woman eating an apple, and then reframing it by saying she is in the garden of eden, and named Eve.