[7/10]

... while I’m a policeman I’ll never stop smoking or stop thinking that one day I’ll write a very romantic, very sweet, very squalid novel, but I’ll also plug away at routine enquiries. When I’m no longer a policeman and write my novel, I’d like to work with lunatics because I love lunatics.

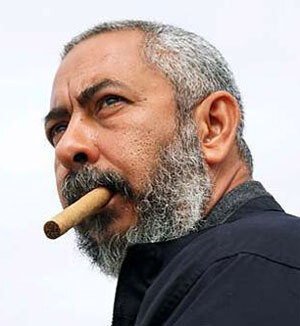

Introducing Mario Conde, a Havana investigator with a sideline in existentialist anguish and a keen eye for the beautiful shapes of women passing by. I’ve always wished I could visit Cuba, hike up in the mountains, swim in the blue Caribbean, dance late at night to popular music. It might take a while for me to actually get there, but in the meantime I was psyched when my friends over in Pulp Fiction voted for Leonardo Padura this month.

Mario Conde’s strolls down memory lane always ended in melancholy.

The novel delivered the goods, most of the time. I felt transported into the ‘squalid’ splendor of the tropical metropolis, with many details in the detective flashbacks or in his present day [1990] strolls through town evoking my own experiences behind the Iron Curtain, starting with the very first morning when Conde wakes miserably after a late drinking night, blaming his hangover on the half-shitty Rumanian plonk he drank to excess. Ironically, in my student days, we used to drink Havana Club rum and smoke cheap Populares cigarettes that Castro was sending over to Romania in exchange for oil and weapons.

The Count, as he is known at the police headquarters, is called back from weekend leave in order to investigate the disappearance of a high ranking government official. Right from the start, Mario Conde feels out of his comfort zone, despite his ten years experience in the force and his reputation as the best detective on the team. Because the missing man, Rafael Morin, is not a stranger to the Count but a former school colleague and the current husband of a girl he was in love with.

Rafael was as squeaky clean as ever, and Conde shouldn’t let his prejudices get the better of him.

His memories were scars from wounds he’d thought had healed a long time ago and a case under investigation was quite another matter, and investigations have antecedents, evidence, clues, suspicions, hunches, intuitions, certainties, comparable statistical data, fingerprints, documents and many, many coincidences but nothing as tricky and treacherous as prejudice.

I liked the way the author uses this old relationship as a catalyst for frequent flashbacks, fleshing out the characters of the policeman and of his prey, building up an entire edifice of youthful dreams and resentments, shared experiences and character traits that will eventually become clues to the reasons a man with a monumental ambition, a successful career and a beautiful wife has gone AWOL.

The focus on social issues, on a clinically depressed detective and on the minute procedural details of the investigation made me think often of parallels between this first Havana novel by Padura and his Swedish mentors Maj Sjowall and Per Wahloo. Mario Conde feels like a carbon copy of Martin Beck, with the main difference residing in the Count’s hot pursuit of anything in a skirt ( Mario Conde savoured her lusty feminity. ) and his self-destructive drinking habits. while Beck was a laid-back introvert. The disillusionment with humanity and the professionalism are shared.

He hardly read nowadays and had even forgotten the day when he’d pledged before a photo of Hemingway, the idol he most worshiped, that he’d be a writer and nothing else and that any other adventures would be valid as life experience.

Life experience.

Dead bodies, suicides, murderers, smugglers, whores, pimps, rapists and raped, thieves, sadists, twisted people of every shape, size, sex, age, colour, social and geographical origins. A load of bastards.

And fingerprints, autopsies, digging, bullets fired, scissors, knives, crowbars, hair and teeth extracted, faces disfigured.

His life experiences.

I also feel the author often identifies with his detective, a psychologist who dreams of becoming a writer and who likes to insert in the text references to Hemingway, Cortazar or Thornton Wilder. They are all appropriate in context and helpful in making a mental picture of Mario Conde and of the reasons he became such a wreck at barely thirty years of age. It’s not an easy job, dealing with the worst of humanity on a daily basis. In another oblique reference to a Sidney Pollack movie we get a possible glimpse at how the author visualizes his lead character : Al Pacino in “Bobby Deerfield” , another personal favorite from my school days.

Just imagine, man, my old dad couldn’t even give a hundred and forty pesos to buy myself a guitar!

On the plus side, Padura has a vibe of authenticity, of a genuine witness account of the problems faced by Cubans in their day to day pursuits. He is critical of the system and of those petty tyrants and small crooks who seem to thrive in totalitarian regimes. Yet I find it easier to relate to these issues, when they are not needlessly politicized or used as propaganda for a regime change. The Count and his friends are equally critical of the greed and duplicity inherent to a money driven system, one where the wolves are appointed as shepherds to the flock.

“Boss, I don’t know why you’re shocked at the lack of controls in an enterprise. Whenever and wherever they do a really surprise audit, they find dreadful things that beggar belief, that nobody can explain, but which are for real.”

I have spoken very little about the actual investigation, not so much out of a fear of spoilers, but because the whole point of the novel seems to be the psychology of the main actors, The Count and Rafael Morin, as revealed through memories and small investigation clues. Together with the side characters, the canvas is expanded to a multi-layered portrait at the city at this particular moment in time – 1990 – a time for change and for re-evaluation of the system of values. More that the expected local colour of rum and cigars, hot-blooded women and popular love songs, the key word that the author returns to time and time again is ‘squalor’ – something of an artistic credo that he builds his story around, an open question that might or might not be resolved in the following books in the series.

I am intrigued enough to follow up.

>>><<<>>><<<

Rating the novel is not easy. I liked parts of it, but my reading experience was not a thrill. It may be the case of a poor translation, but the prose itself left me cold, and the Count himself was half genuine, half a poseur. The sexual details felt gratuitous and the jokes forced, yet a few pages later I felt compelled to bookmark a particularly neat passage. Intellectually, I enjoy the proposition to depict Cuban society as ‘squalid’, but emotionally I was uninvolved in the anguish of the policeman.

The case itself was boring (a deliberate feature in most police procedurals) and the solution entirely predictable, making me think the whole novel is just a pretext for a trip down memory lane.