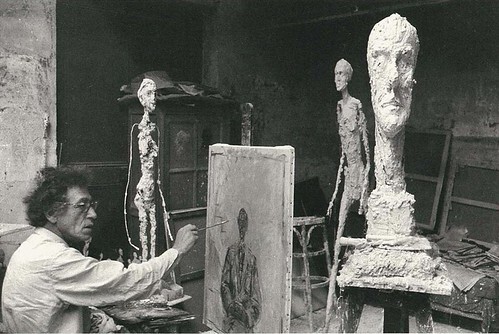

Recently I had the good fortune to attend a showing of a collection of Alberto Giacometti’s work at the Nelson-Atkins Art Museum in Kansas City; one of the finest art museums in the world. I was intrigued by his work and learned that Giacometti is considered an existential artist. Having seen “Final Portrait” starring Geoffrey Rush as Giacometti and Armie Hammer as James Lord which is based on this book, I was intrigued by this artist and his body of work.

Giacometti was one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century. His work was particularly influenced by artistic styles such as Cubism and Surrealism. Philosophical questions about the human condition, as well as existential and phenomenological debates played a significant role in his work. Around 1935 he gave up on his Surrealist influences to pursue a more deepened analysis of figurative compositions. Giacometti wrote texts for periodicals and exhibition catalogues and recorded his thoughts and memories in notebooks and diaries. His critical nature led to self-doubt about his own work and his self-perceived inability to do justice to his own artistic vision. His insecurities nevertheless remained a powerful motivating artistic force throughout his entire life as noted by James Lord in Chapter 17, which coincides with the seventeenth (17th) day he posed for Giacometti:

“I suppose there’s no use in my saying a thing,” I said when we started work together the following afternoon.

“About what?” he asked, then added at once, “Oh, about leaving the picture as it is. That’s out!”

“All right,” I said, “go ahead and demolish it.”

He began to paint. At the beginning he seemed very optimistic. He said, “It’s really rolling along today.” And a little later, “Now I’m doing something that I’ve never done before. I have a very large opening in front of me. It’s the first time in my life that I’ve ever had such an opening.”

Anyone who knows Giacometti at all well has certainly heard him say that he has just then for the first time in his life come to feel that he is on the verge of actually achieving something. And no doubt that is his sincere conviction at the moment. But to a detached observer it may seem that the particular piece of work that provokes this reaction is not radically different from those which have preceded it. Moreover, it will in all likelihood not seem radically different from those that follow, some of which will certainly provoke the same reaction. In short, the reaction is far more an expression of this total creative attitude than of his momentary relation to any single work in progress. He might deny this, but I believe that it is true. Probably, as a matter of fact, it would be vital for him to deny it, because in the earnest sincerity of the specific reaction dwells the decisive strength of all the others, past and to come. If Giacometti cannot feel that something exists true for the first time, then it will not really exist for him at all. From this almost childlike and obsessive response to the nature and the appearance of reality springs true originality of vision.

The plot to this fascinating little book is slim but chockful of insights into Giacometti’s insecurity and artistic genius. In Paris 1964, famed sculptor Alberto Giacometti bumps into his old friend James Lord, an American critic, and asks him to be a model for his latest portrait in his studio for a couple of days. Flattered by the request, Lord complies and is told that only two days are needed to do the portrait. Giacometti lives with his wife Annette and also with his brother Diego at his studio which he also uses as a home. Giacometti also has a favorite muse whom he uses as a model and part time concubine who is the source of some tension in his home.

When the two days pass, Giacometti requests that the sittings with Lord continue for another week. Lord is busy and needs to return to his work back home, though the chance to have his portrait done by Giacometti entices him to stay. He delays his departure accordingly and puts off his writing assignments. Giacometti's progress on the portrait appears to move in starts and stops. Often he is in the habit of simply blanking out the face to start over again. Lord keeps taking photos of the progress, but the progress often is stifled when Giacometti completely rethinks his approach and restarts the portrait from scratch.

The progress on the portrait continues very slowly as one week passes into a second week and a third week. Lord is becoming concerned for the long delays with the portrait and tries to recruit Giacometti's brother to assist him in getting his brother to work a little faster, though his brother completely refuses to do anything like this knowing his brother's prickly temperament. As the portrait painting enters its final stages, Lord eventually departs for his office abroad and reflects on what to him was a firsthand witnessed account of the artistic process of Giacometti's genius of artistry at work.

Giacometti achieved exquisite realism with facility when he was executing busts in his early adolescence, Giacometti's difficulty in re-approaching the figure as an adult is generally understood as a sign of existential struggle for meaning, rather than as a technical deficit.

Giacometti was a key player in the Surrealist art movement, but his work resists easy categorization. Some describe it as formalist, others argue it is expressionist or otherwise having to do with what Deleuze calls "blocs of sensation" (as in Deleuze's analysis of Francis Bacon). Even after his excommunication from the Surrealist group, while the intention of his sculpting was usually imitation, the end products were an expression of his emotional response to the subject. He attempted to create renditions of his models the way he saw them, and the way he thought they ought to be seen. He once said that he was sculpting not the human figure but "the shadow that is cast".

Scholar William Barrett in "Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy" (1962), argues that the attenuated forms of Giacometti’s figures reflect the view of 20th century modernism and existentialism that modern life is increasingly empty and devoid of meaning. "All the sculptures of today, like those of the past, will end one day in pieces...So it is important to fashion one's work carefully in its smallest recess and charge every particle of matter with life."

Read this book and then see the movie "Final Portrait" and then get your bad ol' self to Kansas City and the Nelson-Atkins Art Museum to see one of the finest collections of this mad genius' work before it leaves. You'll be glad you did. Rock on mes Amigas & mes Amigos. 'Tis a rollicking GREAT reading life!