I cannot bring myself to assign stars to this book because I honestly don't know what I'd be rating. The story OF the book (as opposed to the story IN the book) is remarkable. This novel, which is about the experiences of an established German-Jewish family as the Nazis came to power in the early 1930s, was written in 1932 and published in 1933. To put this date in perspective, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany in January of that year; in February he used the burning of the Reichstag (i.e., parliament) as an excuse to seize absolute power. In other words, Feuchtwanger wrote the book as the events he describes were taking place. "In real time," as every review of the book puts it.

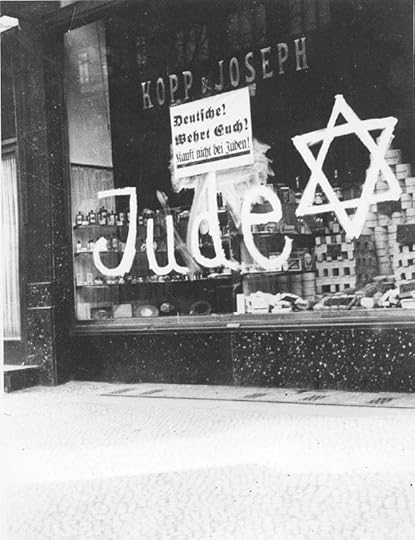

The novel begins with a well-off, respectable German Jewish family celebrating a milestone birthday. Over the course of the chapters that follow we see the deterioration of their status in Germany as the power of the Nazis grows: the business decisions they wrestle with as people become more and more unwilling to buy from Jewish stores or accept treatment from Jewish doctors or representation by Jewish lawyers; how individual members (adults and teens) react to the violent Brown Shirts in the streets, the rumors they hear of torture and death, the appointment of a Nazi official as head of the school attended by the family kids. They debate: such things can't be happening in modern Germany ("A few rowdies wanted to throw a Jew out of a subway train. Well, what of it? They were arrested and would get the punishment they deserved"), or they're temporary and surely civilized Germans will never allow it to continue; do they leave Germany? Where can they go? Stay? Protest? What should people of reason and integrity do in these circumstances? Fight? Be willing to die as a martyr to Reason and Decency?

In short, it's a story we've encountered before. The language too is familiar in it its tone, and we've met this kind of bourgeois German family before. ("The Oppermann's" was originally conceived as a screenplay. It became a novel when the funders of the film backed out under the weight of political pressure. Remnants of that earlier incarnation are clearly evident in the book in the pacing and set pieces.)

Familiar, yes. But never have we encountered a novel like this, on this subject, written precisely as it was happening. Knowing this fact makes reading the book a chilling experience. The author obviously could not, in 1932/3, know what horrors lay ahead. But we do. Questions the characters wrestle with -- "Was it not an impossible undertaking to make a law of anti-Semitism? How was one to know was who was a Jew and who was not?" -- become quite something else to the modern reader who knows that the Nazis made themselves quite adept at sorting out these kinds of questions. And the German people buy into it -- slowly at first, and then in great numbers.

We read passages like this, a meditation by an educator, a man of principle for whom the Nazi propaganda, the rallies and parades with their enthusiastic crowds, beggar belief. Surely people can't believe what the "Leader" and his followers are saying. Why, Hitler is a fool, nearly illiterate! Even the German he used in writing Mein Kampf was terrible: ("The greatest living German, the Leader of the German movement, was not familiar with the rudiments of the German language."

But disdain for something so effete as this is swept away effortlessly by a fist. Does one dare voice a criticism, even softly to a neighbor? No. "If one dared openly to espouse the cause of reason, then the whole herd of Nationalist newspapers would begin to bellow."

So the characters argue and hold their thoughts close, make jokes about "the probable fate of the Leader, whether he would end up as a barker at a fair or as an insurance agent," rationalize ("Do you really believe that, because a few thousand young armed ruffians roam about in the streets, there is an end of Germany?"), keep a low profile. And yet, as one character -- a teenage girl, one of the few characters who sees things clearly -- observes, "It is easy to let the barbarians loose but difficult to get them back into their box."

We know where all this is leading. We know how terrifyingly prescient the author of this book was.

But we also shudder with baleful recognition. I was shaken by how familiar it sounds now to my American ears and eyes: "For months the most eminent experts in the art of lying had been scattering billions of lies throughout the country by means of the most modern devices."

And: "The new authorities were crafty and foolish, but they did do something. That was what the people wanted, and they were impressed by it. Even the Leader, just because of that crafty simplicity of his, untainted by the slightest critical faculty, and on account of his unbending, cast-iron beliefs, was the right man for the people -- the necessary antithesis to the men of yesterday."

I find that I have no lens through which I can look at "the Oppermanns" dispassionately. How can I experience a book like this on its own terms? Do I read the book as historical fiction? As an eyewitness report written "in real time" by a man preternaturally alert to what might (and did) happen?

Or as a warning?