“Parts of the feud remain shrouded in mystery and probably always will. Still, this powerful true saga of love, lust, greed, and rage that ensnared three generations of two families on what was then an isolated and relatively lawless American mountain frontier is graphic enough. Its lessons are about what happens when society’s safeguards are absent or fall apart, when men – armed as they please – are left to their own devices to enforce ‘justice,’ and when family ties determine right and wrong and tribalism prevails. Our self-reliant, wilderness-dwelling forbears often had to grapple with a foe more potent and more relentless than external enemies: their own demons…”

- Dean King, The Feud: The Hatfields & McCoys, The True Story

History is full of feuding families.

Shakespeare used the tale of the 13th century Montagues and Capulets of Italy as the backdrop for his famous love story, Romeo and Juliet. In 17th century Scotland, Clan MacDonald offered hospitality to Clan Campbell at Glencoe, whereupon the Campbells proceeded to butcher the MacDonalds in their sleep. At this very moment, the United Kingdom’s House of Windsor is embroiled in a very public, very tedious intrafamily dispute between rival princes.

Here in the United States, we have the Hatfields and the McCoys.

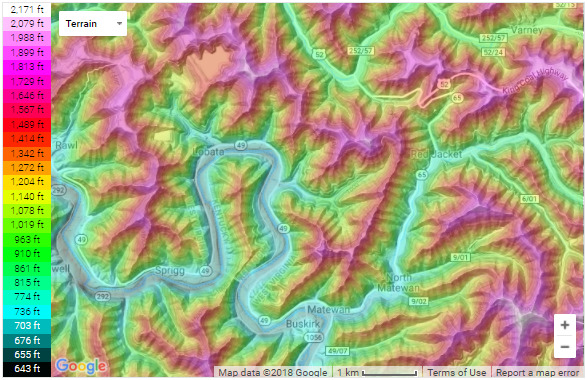

For decades the families of Devil Anse Hatfield and Randall McCoy bludgeoned each other along the rugged border between Kentucky and West Virginia. As described by Dean King in The Feud, the Hatfields and McCoys presented a distinctly American take on the ancient tradition of warring tribes.

In this version, the participants wore their Sunday suits and grew long beards and posed for pictures with bandoliers of ammunition slung over their shoulders. There were gunfights, executions, kidnappings, and – of course – some star-crossed love affairs. Heavily armed and fueled by moonshine, the feud put a dozen family members into the boneyard, wounded others, and proved to be an enduring display of the nation’s most unfortunate values.

***

The Feud begins with an attempt to tease out the causes of the Hatfield-McCoy enmity. King notes at the outset that there was no single triggering event, but rather an accumulation of grievances, some big, some rather petty.

There was, of course, the divisions caused by the Civil War, between those who’d been Unionists and those who’d been secessionists. The whole of the feud played out against the backdrop of an unreconstructed country, still raw from its costliest war.

Stolen hogs also played a role, with Floyd Hatfield and Randolph McCoy arguing about the provenance of notch-eared pigs. When the matter went to trial, a Hatfield Justice of the Peace ruled for the Hatfields based on the testimony of a witness related to both families. Two McCoy brothers later killed that witness, but were acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

The most obvious inflection point came in August 1882, on Kentucky’s Election Day. Rather than casting ballots, three McCoys fought a drunken Hatfield, killing him. Devil Anse organized a party of vigilantes who intercepted and murdered the three McCoys.

From there, it just got uglier.

***

The early going of The Feud is pretty slow. King has a lot of work to do in introducing us to these squabbling broods, and attempting to disentangle the intertwined family trees. There are a lot of characters involved, some with similar names, some with divided loyalties, some who have married their first cousins, and even though King provides genealogical charts and a running tally of the casualties, it can be hard to keep everyone straight. These initial chapters also cover a lot of ground in a hurry, carrying us from the 1860s to the 1880s.

Once King reaches the Election Day fight and its gory aftermath, The Feud really takes off. From there, the timeline is more condensed, there is a lot more action, and the pacing really improves.

***

Unsurprisingly, given the non-academic, non-world-historical nature of the Hatfields and the McCoys, The Feud is purely a narrative history. Having never read any of King’s books before, I found him to be a pretty good storyteller. The prose sometimes gets away from him, veering into overheated descriptions, but for the most part, it suits the material, which is inherently pulpy.

King also does a fine job with the characters, including ambitious patriarch Devil Anse, his exceptionally lethal son Cap, dubious lawman “Bad” Frank Phillips, and Deputy U.S. Marshal Dan Cunningham, who somehow lived to his nineties.

For all that, King’s chief achievement is in navigating a supremely convoluted, often poorly memorialized sequence of events with a measure of coherence. Unlike fiction, which – it is said – has to make sense, real life plotlines often unspool without any logic whatsoever. King has to deal with unfathomable decision-making, inexplicable twists, and a bit of anticlimax. Somehow, he manages to make sense of most of it, even the part where a Hatfield-McCoy legal case ended up before the United States Supreme Court.

***

The Feud’s best attribute is in the balance it achieves between its seedy, dime-store novel subject matter and its undeniable historicity. King clearly researched the heck out of this, and you can check his work by perusing 51-pages of annotated endnotes. Beyond the old letters, diaries, court transcripts, and newspaper stories, King talked to present-day family members to get their perspectives and oral histories. He also walked the grounds, which allows him to accurately evoke the geography, and even clear up an unlikely legend.

***

Most of the books I read are history books. Oftentimes, I choose titles that help me make sense of the world, by looking at how we got here, and why things are the way they are. But sometimes I just want to be entertained, or inspired, or thrilled, or scared. That’s why I have a dozen titles on the Titanic, and a like number about D-Day.

No intellectual imperatives drove me to pick up The Feud. I was simply in the mood for a hillbilly opera peopled by a cast of memorably unsavory figures willing to kill, maim, and terrify in defense of their hardscrabble kingdoms.

I certainly got what I wanted. Or what I thought I wanted.

It is a testament to King’s abilities that by the end of The Feud, I was more than ready to leave the bloody hollows behind. King achieves everything he set out to do, and the result is incredibly dispiriting to the soul. The men – and some of the women – in these pages are violent, unempathetic, and tempestuous. They are drunks; they are adulterers; they carry weapons without any sense of responsibility, and use them without any notion of consequences. They are driven by irresistible impulses to hurt at the slightest provocation.

Mostly, the Hatfields and McCoys were imbued with a ferocious, inchoate rage, one that fed on itself, becoming its own form of reasoning, its own impetus. Long after the original insults were forgotten, this red-faced, neck-veined, shrill-voiced anger kept the feud going.

It’s the same anger that surrounds us today.