That this mediocre book won a Pulitzer Prize substantially diminishes for me the significance of Pulitzer Prizes.

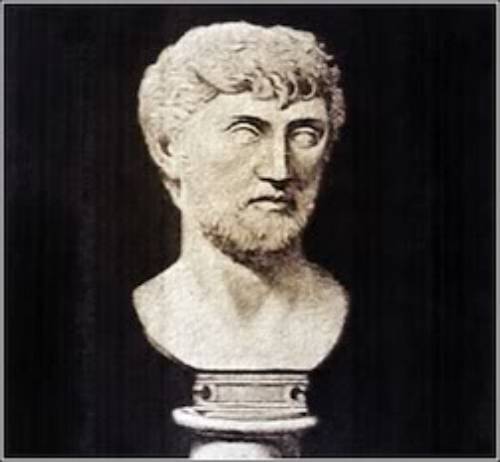

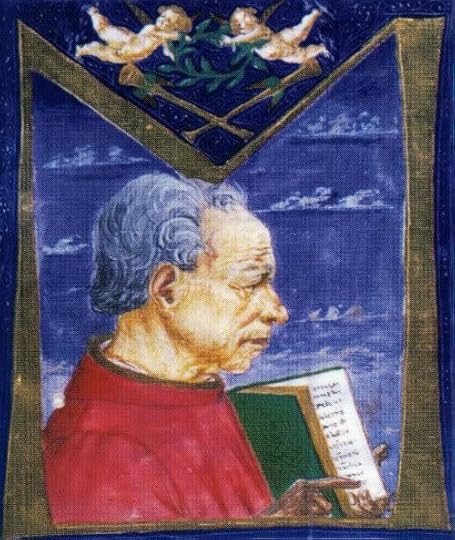

There are two tangentially connected stories here, which Greenblatt tries to weave together. One is a popular, personalized history of the medieval Florentine humanist and bookhunter, Poggio Bracciolini, who is Greenblatt's subject by virtue of being the person rediscovered the book De rerum natura, known in English as On the Nature of Things, by the Epicurean Roman philosopher-poet Lucretius, in a monastery and brought it into circulation among medieval humanists. This story is carried mainly by chapters two, five, six, seven, and nine; makes interesting reading and is generally well-written, though it suffers slightly from being over-written (see below), particularly in the early chapters.

The second "story" is the central conceit of the book that the rediscovery of De rerum natura, played a significant role in changing the world from medieval to modern, and closely tied to it Greenblatt's personal atheistic and anti-Christian theology presented in a very condescending way in which the author assumes that his theology is synonymous with "rationality", though to this observer that seems a rather absurd and ill-founded presumption by Greenblatt. This story is carried primarily in chapters three, four, eight, ten, and eleven. To this reader, there is little binding these two narratives together, despite Greenblatt's attempt to interweave them.

This is where the book fails. The claim at the heart of this story is not made sufficiently. In fact, I find it lacking credibility, not least because the story itself shows us the foundation of modernist thinking already in place prior to the rediscovery of Lucretius' poem! Greenblatt seems aware of how weak his claim is. In the preface he admits “One poem by itself was certainly not responsible for an entire, intellectual, moral, and social transformation…" but, he nevertheless he claims "this particular ancient book, suddenly returning to view, made a difference.” (p.11) and goes on to describe the effect of teh poem as “momentous”, “explosive”, and describe its discovery in terms of "unleashing” a revolutionary force. But looking around at our modern world, where do we see this?

Or looking in this book is the case made? In Chapter Eight Greenblatt provides an itemized summary of points made by Lucretius that he sees as relevant to modernity. Key among these is that Lucretius and the Epicurean's had a theory of atoms, and modern physics has a theory of atoms, but it is debatable how similar the Epicurean's theory of atoms and the modern theory of atoms really are, and the concept of atoms per se, i.e. that there must be some kind of indivisible building blocks of matter, is one logical solution to the potential problem of infinite regress in asking "if things are made of [X], what is X made of?" So the mere use of concept of atoms is not particularly revolutionary or noteworthy, IMO.

Many of the other points in this chapter are fundamentally theological or ontological: "Everything comes into being as a result of a swerve", that is, by randomness in the motion of atoms; this randomness is ultimately the source of "free will"; "The universe was not created for or about humans"; "Humans are not unique"; "The soul dies" with the body; "There is no afterlife"; "All organized religions are superstitious delusions"; "The highest goal of human life is the enhancement of pleasure and the reduction of pain". There is not anything close to consensus in modernity about these claims, nor can they be demonstrated to be true. The claim that all religions are superstitious delusions is highly ironic when one recognizes that the Lucretius' beliefs themselves constitute an organized religion, which incidentally also offers an alternate explanation to that offered by Greenblatt about why the medieval church took exception to them.

In Chapters nine and ten Greenblatt tries to show the influence of Lucretius on Thomas More, Giordano Bruno, and to the founding political ideals of the United States via Thomas Jefferson. Clearly On the Nature of Things enjoyed a well-educated audience with whose views it resonated to greater or lesser degree, but that hardly makes the case for the claims that this work was a foundation of modernist thinking.

I note a number of excerpts from the book that strike me as either presumptious or peculiar:

“Ancient Greeks and Romans did not share our [sic] idealization of isolated geniuses, working alone through the knottiest problems. Such scenes… would eventually become our [sic] dominant emblem of the life of the mind…” (p. 68) This one actually made me laugh out loud at its absurdity and wonder that an author who would write this could win a Pulitzer Prize.

“Why should anyone with any sense credit the idea of Providence, a childish idea contradicted by any [sic] rational adult’s experience and observation? Christians are like a council of frogs in a pond, croaking at the top of their lungs, ‘For our sakes was the world created.’” (p. 98) The latter sentence seems to me based on a deeply flawed stereotype about Christian beliefs, though perhaps that stereotype had greater validity in medieval times. The first sentence is where, IMO, the real problem lies. Providence is, IMO, one of just a few possible explanations for things that I have experienced and observed in my lifetime, and which I assume many other people experience, and while there could certainly be other explanations for those experiences, I fail to see any basis for concluding that a belief in Providence is irrational. Indeed, it seems to me that there have been a great many generally rational people who have believed in Providence. But then again, the model of "Providence" that Greenblatt offers later in his book bears scant resemblance to what that concept means to me. It feels to me like a straw argument of an atheist who wishes to discount it. Unfortunately or fortunately, depending on which side of the debate one stands on, what would be needed to dispel the idea is beyond the possibility of empirical evidence. Which again makes me wonder how the Pulitzer Prize would be awarded to such obviously flawed logic.

Another example of logic flaws are the various teleologies that the author articulates e.g. “What had to be done was…” (p.101), “Centuries were required to accomplish this grand design [sic]…”

Greenblatt writes “Though early Christians… found certain features in Epicureanism admirable…" but then writes "Christians particularly found Epicureanism a noxious threat.” (p. 101) These seems almost self-contradictory. How noxious a threat could it have been if some portions of it were admirable?

Similarly Greenblatt writes "Lucretius was not in fact an atheist…" but then "It is possible to argue that… Lucretius was some sort of atheist…” (p.183) and then again “the set of convictions articulated… in Lucretius’ poem was virtually a textbook… definition of atheism” (p. 221). ?!?

“As every pious reader of Luke’s Gospel knew, Jesus wept, but there were no verses that described him laughing or smiling, let alone pursuing pleasure.” [p.105] There may be no versus that specifically mention Jesus laughing or smiling, but there are a number of scenes mention in the gospels that seem, to this observer, to defy the claim here that Jesus rejects pleasure altogether, including the wedding at Cana, Jesus eating with sinners, Martha annointing him, and especially the observation of some of his contemporaries that he did not affect the mourning/fasting countenance of John the Baptist, and his reply “Can you make the guests mourn while they are with the bridegroom? (Luke 5:34)

Throughout the book, and especially in Chapter four, Greenblatt portrays Christians, at least ardent medieval Christians, as superstitious, irrational, and enemies to mankind. In the context of medieval Christianity, some of that is warranted, but I think the effort to extend it to Christianity generally across time is to conflate the thinking of medieval religious institutions with Christian theology generally.

Greenblatt also has an elitist, derisive view toward less educated, common people, e.g. peasants, artisans, farmers, etc, which is evident at various points in his writing.

The book, especially the early chapters, suffers somewhat from over-writing, by which I mean: (1) some paragraphs are redundant of prior paragraphs, belaboring the point or assuming that the audience is deficient in attention span, as in the manner of a contemporary TV shows that, after each commercial break, give you a synopsis of what they have already covered; (2) the author sometimes wants to tell you what you should think about the things he has described rather than merely describing them and leaving the thinking to the reader, though mercifully that aspect of over-writtenness is minor in this book; (3) the author presents certain information, most notably Poggio's THOUGHTS, and certain presumed "truths" about the universe, which he cannot know, but can only speculate on or assume, aided in the former instance by analysis of Poggio's writings; and especially (4) that the author goes on at length and with various digressions to tell at length what could be said better more succinctly. Greenblatt will offer a half a chapter with unneeded digressions on a half dozen topics to tell you what a lesser writer might have narrated more effectively in a page or two.

“The link [to Poggio’s grandfather] is worth noting because…. [the grandfather] signed a notarial register with a strikingly beautiful signature. Penmanship would turn out to play an oddly important role in the grandson’s story.” (p.112) Really, a paragraph on the grandfather is important because the grandfather and his grandson both had beautiful handwriting?!

In summary, reading the biographical history of Poggio Bracciolini is interesting, as are some of the digressive narratives insofar as they contribute to that story, but the writing suffers from over-writing, flawed assumptions, and certain biases that I find repugnant. Most of all I don't find Lucretius' poem particularly relevant to the modern world and IMO the author fails to make a compelling, or even credible case that it was.