What do you think?

Rate this book

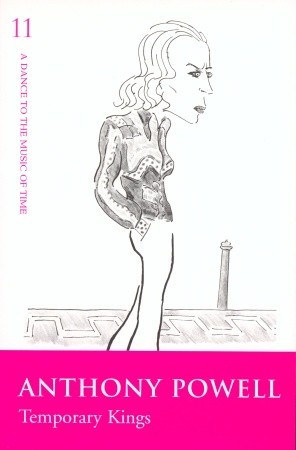

A Dance to the Music of Time – his brilliant 12-novel sequence, which chronicles the lives of over three hundred characters, is a unique evocation of life in twentieth-century England.

The novels follow Nicholas Jenkins, Kenneth Widmerpool and others, as they negotiate the intellectual, cultural and social hurdles that stand between them and the “Acceptance World.”

288 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1973

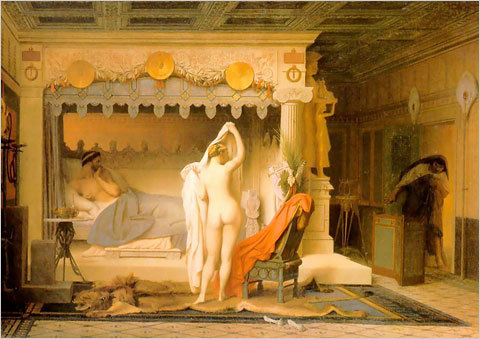

‘You’ll live like a king once you get there.’

‘One of those temporary kings in The Golden Bough, everything at their disposal for a year or a month or a day – then execution? Death in Venice?’

‘Only ritual execution in more enlightened times – the image of a declining virility. A Mann’s a man for a’ that. Being the temporary king is what matters.’