A whole lot more than Western noir

When I was in 5th grade and was required to memorize a poem, my father suggested that I commit Robert W. Service's The Cremation of Sam McGee to memory. So, from the age of 10, movies like Sierra Madre have summoned the famous Service line:

There are strange things done 'neath the midnight sun—by the men who moil for gold.

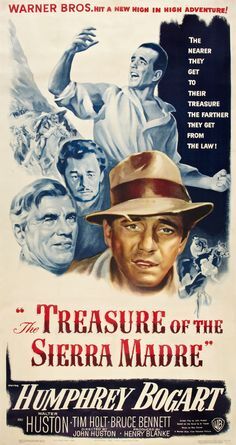

In particular, Service and the 1948 John Huston and Humphrey Bogart movie version were fused together in my mind. Because my father loved Westerns, I saw that classic with him around that same time I was memorizing Service. I immediately understood the story Huston put onto the screen as a parable of greed's corrupting influence to the point that ultimately the greedy don't win. They can't win—because they are consumed by their own folly. Or, so I understood these lessons back at that early age.

So, what a shock it was for me in college to discover B. Traven and, among several of his novels that I consumed, was the original 1927 (in German, then 1935 in English) The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. I actually had been assigned, in a comparative literature course, to read at least two of Traven's "Jungle Novels" before I finally got to Sierra Madre. So, by the time I read his original version of Sierra Madre, I understood that the mysterious B. Traven was digging for truths far deeper and more profound than gold.

As I emerged from college as a journalist in the mid 1970s, B. Traven remained a favorite author because no one seemed to be able to pin down his identity definitively. "Presumed to be German" and "lived for years in Mexico" are the two points of global consensus as of 2024. The other truth that is self evident from his novels is: He had a personal passion for the plight of the oppressed.

So, was B. Traven really a famous German anarchist who published an anarchist newspaper as well? Maybe. Or maybe not. There are at least several leading theories on his identity.

In any case, the beating heart of Traven's novels is the ruthless cruelty with which powerful men (and sometimes powerful women) could pursue their fortunes. Traven truly cared about the countless indigenous and minority communities that were slashed and burned through centuries of conquest and ongoing political, social and economic corruption in the Americas.

Is this just my interpretation, based on the plot twists? No, in fact, B. Traven makes his viewpoint quite clear! There are several passages in Sierra Madre in which Traven turns to readers—as if a character in John Huston's movie had suddenly decided to address the audience—and Traven preaches about the tragedy and trauma of this global-scale system of oppression.

A third of the way into Sierra Madre, for example, he writes:

The gold worn around the finger of an elegant lady or as a crown on the head of a king has more often than not passed through hands of creatures who would make that king or that elegant lady shudder. There is little doubt that gold is oftener bathed in human blood than in hot suds. A noble king who wished to show his high-mindedness could do no better than have his crown made of iron. Gold is for thieves and swindlers. For this reason they own most of it. The rest is owned by those who do not care where the gold comes from or in what sort of hands it has been.

Later in the novel, B. Traven also pauses in the narration to launch a full-scale indictment of the Catholic church for historically teaching, blessing and enforcing this cruel system of domination of the poor by the powerful. Whoever B. Traven really was, he had a deep understanding of the injustices that stemmed from the 1492 collision of Old and New Worlds and the centuries of slavery and oppression that followed in the Americas.

(And a note of clarification: Certainly, today, the Catholic church is a different institution than it was in the early centuries of colonization. As a journalist who specializes in religious diversity, I have reported on that evolution. But, even Catholic leaders today would acknowledge that B. Traven was at least partially correct in his indictment of oppression in the colonial era.)

So, reading the novel, even if you know the classic film by heart, is an entirely different experience.

Yes, many key scenes in the novel were translated (with some softening) directly into Huston's film. There are many differences, of course. The actual "stinking badges" quote is more brutal in the book than Hollywood censors allowed in the movie. And, well, there's a whole lot more action in the book—some of it quite violent—that was left on Huston's cutting room floor.

For instance, if you want an example of one of B. Traven's particularly greedy and violent rich woman, there's one in the middle of this novel who make you wince as you read her tale. But, her tangential story never made it into the movie, either.

I'm adding this review simply because it may prompt a few Goodreads friends to revisit the original by B. Traven. Even if the movie is seared into your memory, the actual novel is an eye-opening vision of a far larger and much more troubling world.

And who knows? Maybe some day I can update this review if some researcher ever does nail down B. Traven's identity. At least for now, the mystery continues far beyond the novel's pages.