American Mirror was the most entertaining book I've read this year. I read it straight through without skipping the boring parts, because there just weren't any. Author Deborah Solomon is an art critic as well as a biographer, so that brought an extra dimension to the life story. It was every bit as much about the art as about the man.

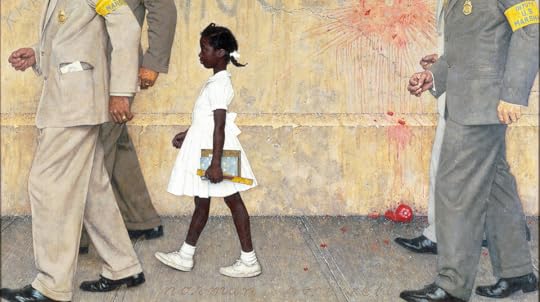

I've always had a love/hate attitude toward Rockwell's illustrations. I admire the composition and the realism, but I hate the cutesy facial expressions. But the pictures are fascinating to look at, you can spend as much time and imagination on them as you can with Edward Hopper's paintings. And after reading Richard Halpern's Norman Rockwell: The Underside of Innocence, I find it impossible not to look for the dark side of the story in them.

Solomon takes the story further, by exploring Rockwell's influences, both the artists that were from the generation before his that he'd grown up studying, and his contemporaries, as well as the massive effect the modernist movement had on all western art from the 1910s through mid century. She notes that he often consulted numerous art books for ideas and inspiration, and shows the overt nods he made to the masters, such as in his Rosie the Riveter pose, and his Triple Self Portrait.

As for Rockwell the man, Solomon finds a needy, sometimes bitter man, one who upon learning that his brother's long time girlfriend had accepted his (brother's) proposal of marriage, immediately proposed to her himself. He seemed to prefer the company of men to that of women, although he married three times. Rockwell was self-effacing to the point of insecurity, insisting that he was not an artist, he was merely an illustrator.

I liked the style of writing -- Solomon is direct and informative, and keeps a documentarian's distance, except on rare occasion when she just can't resist. "It is odd to think of three married men (two of whom had young children) leaving their wives for two months to frolic in Europe -- the [1920s] sometimes seem too silly for words."

Plenty of illustrations, photographs, and a full color insert of Rockwell paintings for easy reference. Five stars!