“And now ensued one of the greatest scenes of war that can be conceived; if we look to the height, Howe’s corps, ascending the hill in the face of entrenchments, and in a very disadvantageous ground, was much engaged; to the left the enemy pouring in fresh troops by the thousands, over the land; and in the arm of the sea our ships and floating batteries cannonading them; straight before us a large and noble town in one great blaze – the church steeples, being timber, were great pyramids of fire above the rest…The roar of cannon, mortars and musketry; the crash of churches, ships upon stocks, and whole streets falling together, to fill the ear; the storm of the redoubts…to fill the eye; and the reflection that, perhaps, a defeat was a final loss to the British Empire in America…”

- General John Burgoyne, in a letter to his nephew, Lord Stanley, June 25, 1775

The American Revolution was not – relatively speaking – an overly-bloody conflict. The number of battle-related casualties was small compared to contemporary European conflicts and later American wars. Far, far, far more men died of disease than of wounds.

The Battle of Bunker Hill (which took place mostly on Breed’s Hill) was an exception. It did not involve a huge number of men; estimates at the high range put the combined Colonial-British forces at around 6,000 soldiers. Yet the fighting was hot, fierce, and lethal. The historian Alexander Rose puts total British casualties at 44% of all men engaged, with the Colonials suffering around 16.5% casualties. It was the costliest battle of the American Revolution.

In Nathaniel Philbrick’s Bunker Hill, however, the battle plays only a small role in the proceedings. This, instead, is the story of Boston at the dawn of the United States. It begins with the 1773 Boston Tea Party and ends with the British withdrawing from the city in 1776. In between is the formation of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, the battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, and George Washington’s siege. In a hair less than 300 pages of text, Philbrick takes us through the process in which a protest became a revolution, a revolution turned into a battle, and a battle sparked a war for independence.

Nothing in American history has been so mythologized and simplified than the “War of Independence.” Philbrick brings back the complications without making things complicated. In graceful prose, he narrates how the policy of “salutary neglect” backfired on Great Britain. For years, the colonies had experienced economic growth without paying the taxes shouldered by other British subjects. This ended in the wake of the French and Indian War. A great sum of money had been spent defending the colonies from France, and Parliament decided it was time for Americans to pay their share.

Thus followed a series of taxes levied and repealed, levied and repealed. Parliament would make a move, the colonists would protest, and Parliament would back off. Tellingly, this occurred within a context in which even the most ardent protester sought change within the existing paradigm. They didn't want to leave Great Britain; they just wanted better terms. That all changed in 1775, when Great Britain sent troops to occupy Boston. Suddenly, the cats and dogs were living together. It is not surprising that blood was shed. Even so, a complete break with Great Britain was not a foregone conclusion until the collision on Charlestown Peninsula.

I’ve read several of Philbrick’s books. Strange to say, I’ve never loved a single one of them. Yet, taken as a body of work, I think he’s one of the best popular historians working today. One of the reasons is his facility with personalities. Philbrick recognizes history as drama, and historical figures as characters. He does a fine job humanizing the players. In Bunker Hill, top billing does not go to the usual suspects, such as firebrand Sam Adams, but rather to Dr. Joseph Warren, an ambitious physician, lover, and rabble rouser who rose to the presidency of the Provincial Congress, became a major general in the nascent Provincial Army, and died on Breed’s Hill fighting as a private. Philbrick is clearly enamored of Warren, and muses at the course of events had Warren survived. I’ve not read nearly enough to cast judgment on Philbrick’s treatment of Warren; nonetheless, I found it a spirited bit of revisionism.

Aside from illuminating bios, Philbrick is also very good with enlivening details and factoids. For instance, the tea infamously dumped into Boston Harbor was actually being sold at a fraction of its cost in order to get rid of the East India Company’s surplus. However, built into that fire-sale price was a small tax that infuriated many colonists despite the net windfall for consumers. For Great Britain, this was an unforced error. Of course, American anger wasn’t all on principle. Rich and gouty John Hancock, he of the heroic signature line, was a tea smuggler who lost profits when the East India tea undercut his prices.

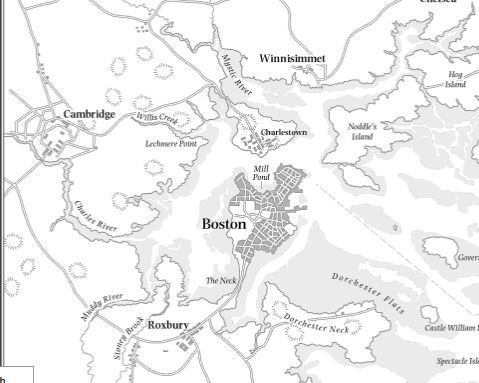

As I mentioned above, the actual battle of Bunker Hill comprises only a single chapter. The retelling of the fight is competent, if not overly memorable. Alexander Rose’s Bunker Hill chapter in Men of War is a far superior retelling. Philbrick’s real achievement is not in the realm of military history, but in tracking how this engagement came about, and interpreting what it meant. Typical for Philbrick, he has consulted a wide range of sources that he lists and discusses in 56 pages of annotated endnotes. Bunker Hill also gets points for presentation, on top of its content. There are a decent number of maps, and two photo insets, including one inset in full color. (I don’t usually remark on the inclusion/exclusion of pictures, since it’s hard to do without sounding like my five year-old. Still, it’s really neat when an author describes a famous portrait, and then it’s right there, in the book. Nothing breaks up the flow of a reading experience more than the irresistible temptation to look something up on my phone).

Philbrick brings a healthy dose of Nantucket contrarianism to this book. He recognizes that revolutions are messy, and the American Revolution no exception. There were no guillotines, thankfully, but there was a lot of tarring and feathering, property destruction, physical violence, and mob rule. The American “patriots” were, at times, nothing more than thugs, and their vigilantism and neighborhood despotism more than a little terrifying. As the Reverend Mather Byles remarked: “Tell me, which is better, to be ruled by one tyrant 3,000 miles away, or by 3,000 tyrants not a mile away?”

This kind of sharp edged history, unafraid of sacred cows, is important for a topic like this. The revolutionary period still exists in the halcyon glow possessed by many origin stories. The men and women of this period were not infallible; that should be obvious, though many still look to them in determining the role of government in our lives today. If we are to give ghosts such power over the living, it is always worth remembering who, exactly, they were, and what, exactly, they stood for. Bunker Hill has a bursting dramatis personae. Not just Warren and Hancock, but George Washington, John and Abigail Adams, Paul Revere, and many more. Philbrick captures them in their honor and venality, in their courage and cowardice, in their insights, both brilliant and blundering.