What do you think?

Rate this book

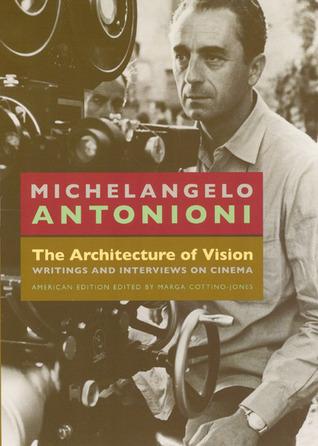

430 pages, Paperback

First published July 1, 1996

This book unites Antonioni's defenses/essays of his films with interviews from the 1950s-80s to certain success if some of the content is ultimately redundant. There are numerous editorial oversights, but I think those flaws are eclipsed by intriguing philosophizing and Antonioni's ideas for films that unfortunately never came to fruition. I'm currently developing a screenplay (or at least I'm trying to), and on more than a few occasions, I documented his advice. The thirteen pages of "My Experience" and "Making a Film is My Way of Life" are probably just as enlightening as any screenwriting-prep book.

Since I discovered Antonioni on my own, I've had a tenuous relationship with him. Italian cinema of the late 1950s-60s period is extraordinarily dense even if it seems to give off this accessible first impression. Where I might suggest the average person check out one of Fellini's zany carnivalesque offerings, Antonioni's work, on the other hand, doesn't garner much appeal outside the intellectualist cinema circle. Modern viewers of more casual cinema call him "pretentious," but that strikes me as a misnomer when they probably mean "elitist." (Okay, sure, haha). Critics don't understand that Antonioni was never looking for exact, conventional resolves; his entire purpose is to abstract. He's more interested in studying interior contradictions of humanity. In the "Gaze and the Story" introduction, Giorgio Tinazzi writes that Antonioni's method of storytelling "gives expression to zones of thought and consciousness that have little space in conventional narrative. They are moments of experience which are recovered." Yes, his is a cinema of moments, which generally grow increasingly visual with each successive film. Essentially, Antonioni is trusting an inner intuitive voice/image to construct the rhythm of a movie rather than pure logic. Perhaps this is why there are many nagging questions about behaviors and fates of certain characters. I suppose there is still part of me that views his approach as irresponsible, but I've come to focus on the value of his psychological contemplations- articulations of life's uncertainties, characters transformed by their environments/on-screen space, societal immorality. Antonioni occupies an interesting niche realm where his films aren't necessarily avant-garde, but they don't feel linear either. I think once one becomes accustomed to the director's way of deconstructing cinematic rules, it's hard to identify the value in the golden age of Hollywood constructs. All those glamorizing façades are now exposed.

This book should really articulate any vague notions one may have had about Antonioni after encountering a couple of his films- that he operates with a rigid philosophy unique to the moving image; his thoughts on cinéma vérité (pg. 178) are the narrator (pg. 75) are particularly resonant. But for me, as someone who's spent a lot of time analyzing movies (among other mediums) over the years, most meaningful is his belief that "without criticism, art would lose its strongest supporter." With someone like Antonioni, who has been met with extreme initial criticism by those who have gone on to become his advocates, this is most affecting. Not everyone will feel this way, but the director is suggesting, in his own way, that we all get a little closer to cinema itself through its study to promote understanding.