This was such a strangely quiet book, contrasting with most of the fiction I've been reading lately, a novel about a life lived in exile, one's tentative but pervasive ties to others also living in that limbo, always aware of that steel cable of home, family and country.

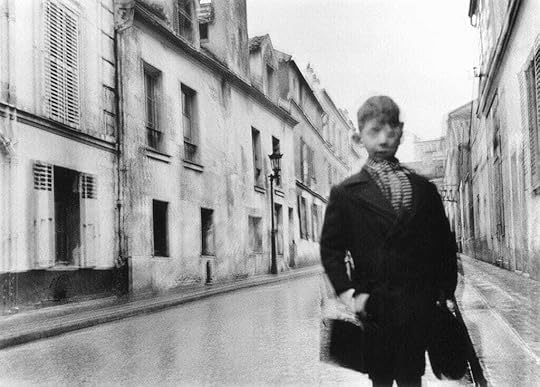

Khaled is a middle-aged Libyan man living in London when we meet him, but the time is very fluid in the book. He's a boy in the bosom of his family, with a cautious but respected teacher father, a smart boy, listening to a mysterious author's short story on the radio from England, on the ARab language BBC, and there are intimations that we will later meet that author. Then he is a student on a government sponsored scholarship to Edinburgh, where he falls in with a group of Libyan students, his first group of friends.

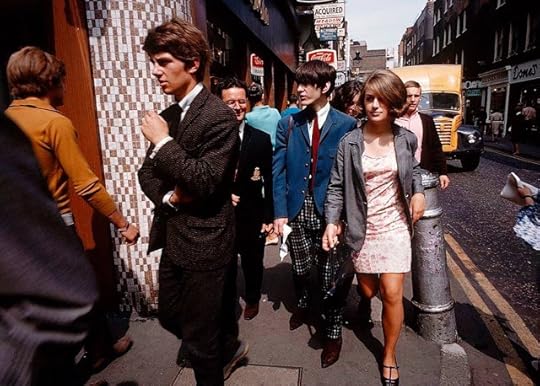

Then he's in London with one of them, Mustafa, where, for a lark, they decide to attend a demonstration against Qaddafi at the Libyan Embassy. Suitably garbed in balaclavas, as the Qaddafi regime is quite murderous about any kind of protest, there is a shocking break in Khaled's life. In a well-documented incident, the demonstrators are fired upon from inside the Embassy. Mustafa escapes, but Khaled is shot, and after hospitalization and recovery, he realizes that his chances of ever returning home are nil.

The book traces his relationship with Mustafa and others, girls and boys, women and men, his inability to even tell anyone, including--most of all--his parents what has happened to him for fear of the regime's reprisals. Khaled is not an immigrant to England, he makes little effort to truly immigrate and make a new life for himself. What happens is--his life stops. He is left circling that moment, emotionally stuck. He eventually becomes friends with that mysterious author, who himself has become an exile, Hosam Howa, and he moves between Mustafa and Hosam in an interesting dance.

Eventually, with the start of Arab Spring, Mustafa--the least political of them--returns to fight against the regime, and surprisingly to Khaled, Howa returns as well. Libya so much more real to them than their lives in exile. Khaled's choice not to return is the fascinating puzzle at the heart of the book.

The book has a beautiful tone, very internal--it covers some thirty years of Khaled's life, from age 18 to his fifties, the 1984 shooting, to 2016, five years after the death of Qaddafi--and one can follow the history of Libya in those years, the shooting of the students in London, the show trials and the outbreak of the Arab Spring as well as its aftermath. But the timeline is the internal one, the thoughts and life of exile, when even the joy has the hollowness of being not at home. I've been doing a lot of thinking lately about exile, and the book really lets you step into that space.

The writing is beautiful, the character deeply aware of his own state--disappointed in himself, limiting the possibilities of moving ahead as his father did, a brilliant scholar who took a mediocre teaching job in a high school to stay out of the limelight and have a life, diminished but continuing to inspire those around him. The shooting, his exile, gets between Khaled and the rest of life, like looking through a window at it.

The ending was oddly shocking in its quiet way, and made me want to start over.

To give you a sense of tone, here's Khaled with Hosam, shortly after having finally met the writer working as a clerk at a hotel in Paris. They are two Libyans at a cafe, each suspicious of the other, wondering if he might be a Qaddafi agent--calling themselves Sam and Fred. And then 'Fred' begins to talk about himself, about the demonstration, as he never does in his usual life:

"I regret attending," I said, and meant it, but was also wishing to absolve myself. "It's not true what some say, that dying, when in comes, bring with it its own acceptance. The opposite, if you ask me. It brings rebellion. Because you realize then that you've sent every day of your life learning how to live. That you don't know how to do anything else. Certainly not death. And I could see it, the blackness. And could see also how endless it was. But even that wasn't the worst of it. What horrified me was I knew then that part of me, a spot-of-consciousness, would survive and continue even after death, trapped within a nothing and silence for eternity."

In other words, more exile.

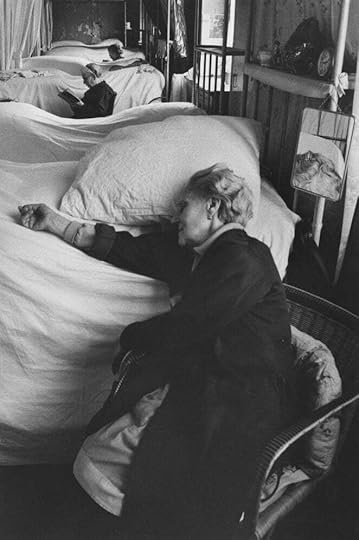

Here's a scene many years later, after Hosam has returned to Libya, after having attending his father's funeral (a well-known father who once denied his writer-son as part of a televised torture-confession):

"In the days after the burial and the wake, Hosam returned to writing me emails. Thee in particular transported me home. I had never since leaving felt more vividly connected to my country. I realized then that I had always somehow anticipated this, perhaps even from as far back as when I was fourteen and first heard his story read on the radio, that he would be a medium, that we ask of writers what we ask of our closest friends, to help us mediate and interpret the world."

This is not a flashy book, not packed with incident and thrills, not about the drama between characters, but unpacking a human life derailed by politics and yet buoyed by friendships. Read it in a quiet mood.