What do you think?

Rate this book

Unknown Binding

First published January 1, 1987

"Patterns of life are selfish and unforgiving."

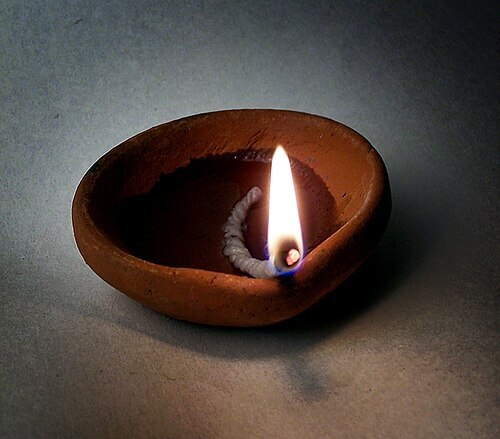

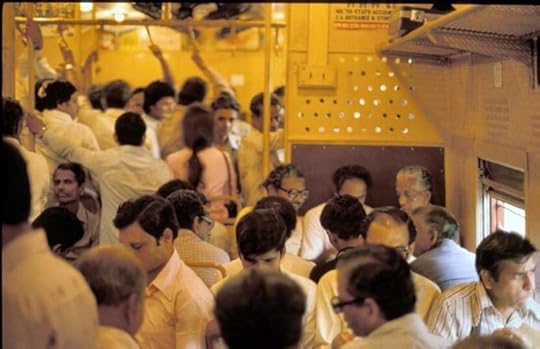

Never will I forget that first day in Bombay. I just stood in one place, not knowing what to do, till Joseph Uncle saw me. Now it has been forty-nine years in this house as ayah, believe or don’t believe. Forty-nine years in Firozsha Baag’s B Block and they still don’t say my name right. Is it so difficult to say Jacqueline? But they always say Jaakaylee. Or worse, Jaakayl.