What do you think?

Rate this book

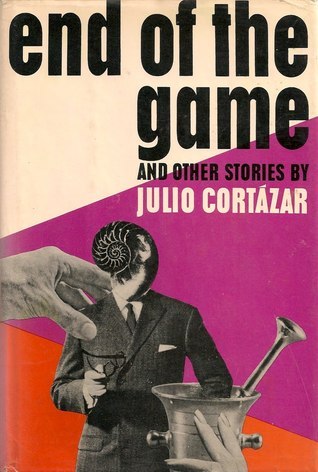

277 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1968

It was their quietness that made me lean toward them fascinated the first time I saw the axolotls. Obscurely I seemed to understand their secret will, to abolish space and time with an indifferent immobility.

Before dropping off to sleep, when faces appear in the darkness, she remembered again the Kid going out onto the porch for a smoke, thin, humming to himself, saw Rema who was bringing him out coffee and he made a mistake taking the cup so clumsily that he caught Rema’s fingers while trying to get the cup, Isabel had seen from the dining room Rema pulling her hand back and the Kid was barely able to keep the cup from falling and laughed at the tangle.

It seems right for me to say here that I come to this dance hall to see the monsters, I know of no other place where you get so many of them at one time. They heave into sight around eleven in the evening, coming down from obscure sections of the city, deliberate and sure, by ones and by twos, the women almost dwarves and very dark, the guys like Javanese or Indians from the north bound into tight black suits or suits with checks, the hard hair painfully plastered down, little drops of brilliantine catching blue and pink reflections, the women with enormously high hairdos which make them look even more like dwarves, tough, laborious hairdos of the sort that let you know there’s nothing left but weariness and pride.

"I prefer the words to the reality that I'm trying to describe.",

In a recent essay, the Argentine writer Fabián Casas recalls his first reading of Hopscotch (‘it was all cryptic, promising, wonderful’) and his later disappointment (‘the book started to seem naive, snobbish, and unbearable’). That is my generation’s experience: sooner rather than later we end up killing the father, even though he was a liberating and quite permissive dad. And it turns out that now we miss him, as Casas says at the end of his essay, in a happy, sentimental turn: ‘I want him to come back. I want us to have writers like him again: forthright, committed, beautiful, forever young, cultured, generous, loud-mouthed.'

Our kingdom was this: a long curve of the tracks ended its bend just opposite the back section of the house. There was just the gravel incline, the crossties, and the double line of track; some dumb sparse grass among the rubble where mica, quartz and feldspar—the components of granite—sparkled like real diamonds in the two o’clock afternoon sun. When we stooped down to touch the rails (not wasting time because it would have been dangerous to spend much time there, not so much from the trains as for fear of being seen from the house), the heat off the stone roadbed flushed our faces, and facing into the wind from the river there was a damp heat against our cheeks and ears. We liked to bend our legs and squat down, rise, squat again, move from one kind of hot zone to the other, watching each other’s faces to measure the perspiration—a minute or two later we would be sopping with it. And we were always quiet, looking down the track into the distance, or at the river on the other side, that stretch of coffee-and-cream river.[from "end of the game"]