What do you think?

Rate this book

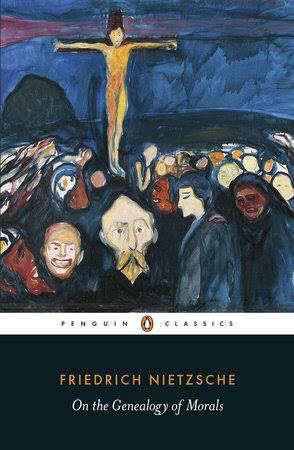

194 pages, Unknown Binding

First published January 1, 1997

"History is a dead weight on the present."

"Any truth which threatens life is no truth at all. It is an error"

—Niezsche

We're being more complex and sophisticated when it comes to description.

"Madness is something rare in individuals – but in groups, parties, peoples, ages, it is the rule."

Conscience: coincides with the beginnings of social structure and law-making, which in turn depend on the repression of instinct and the development of rationality.