As the Christmas season draws near, I am reminded of a beautiful children’s book set in Paris at Christmas time ~ The Family Under the Bridge, by American author Natalie Savage Carlson. The Family Under the Bridge is a celebration of the City of Light, a celebration of generosity and kindness, and a celebration of family sticking together through tough times.

Reading this book is like being taken on a walking tour of Paris. And no ordinary walking tour of Paris ~ a walking tour of Paris conducted by an old hobo who would rather live in Paris than anywhere else.

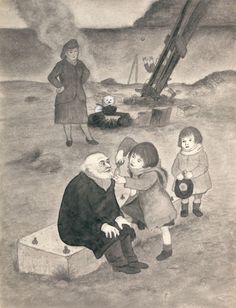

At the beginning of the story, Armand walks past Notre Dame Cathedral. He descends to the cobbled quay along the Seine river and returns to his favored spot under the bridge. It is there that he meets the three homeless children who will steal his heart. Together they walk among the crowd of holiday shoppers on the Rue de Rivoli, visit Father Christmas at the Louvre, and attend a Christmas Eve party under Tournelle Bridge.

When Armand takes the children to see the gypsies, they first stop by Les Halles, the fresh food market, and then walk past St. Eustache Church, down Rue de Petits Carreaux with its “patterns of cobbles so tiny that they looked like mosaic” (58), and on to the gypsy encampment at the Court of Miracles. Other places of mention are the Place Maubert, Rue de Montorgueil, Rue de l’Opera, the Theatre-Francais, and the Jardin des Plantes, the Parisian botanical garden.

Carlson lovingly presents the sights of Paris through the eyes of the Calcet children. One especially pretty scene occurs at the Christmas Eve party under Tournelle Bridge:

“But Suzy’s eyes were looking across the river to the little Isle of the Cité, where Notre Dame was illuminated like a saint’s dream. Its flying buttresses and tall, fragile arrow were frosted with light” (83).

Despite the beauty of this scene, one never forgets that the Calcet children are poor and homeless.

“Paris had turned white overnight. It was a beautiful sight for those who could stand in a warm room and look through a window” (51).

Though their widowed mother works long hours at the laundry, she doesn’t earn enough for rent. Their future is uncertain. Suzy, Paul, and Evelyne are cold and hungry, their clothes are ill-fitting and mismatched, and they cannot even go to school.

The hobo life that so comfortably suits Armand is a calamity for the Calcets, but he shares his food, his philosophy, and his friendship. Armand has cultivated an appreciation for the simple pleasures and virtues of the poor. For lunch, he enjoys the aroma of food coming from a restaurant. He picks through the refuse at a flower stall to find himself a spring of holly for his buttonhole. And he carries around one shoe because it fits well and, who knows, its mate might show up someday. But most importantly, he values the kindness and generosity exhibited by the poor toward each other. This is made explicit when he lectures Madame Calcet on the gypsies. Madame Calcet think gypsies are just thieves, but Armand defends them.

“’What is wrong with gypsies?’ asked Armand. ‘Why do you think you are better? Are you kinder? Are you more generous?‘” (71).

Madame Calcet is an honest and hard-working woman, but she needs help and it is not easy for her to accept the generosity of others. She is upset when she learns that her children accepted food from Armand and she tries to distance herself from the other homeless people at the Christmas Eve party when she offers to help serve the dinner. But Armand reminds her of her own words about family sticking together:

“Well, we’re all God's big poor family, so we need to stick together and help each other” (72).

Setting her pride aside, Madame Calcet accepts the gypsies’ generosity. Armand has taught her a valuable lesson, but he has a lesson to learn as well.

Armand does not like children ~ or so he says. He calls them “starlings” and fears they will steal his heart. But Armand’s real fear is revealed in chapter one:

“These starlings would steal your heart if you didn’t keep it well hidden. And he wanted nothing to do with children. They meant homes and responsibility and regular work—all the things he had turned his back on so long ago” (7-8).

Armand doesn’t like to work. Twice he turns down job offers. This sets him apart from the other poor people in the story, like the hobo Camille who works as a department store Father Christmas, or Louis who works as a pusher at Les Halles, or the gypsies who earn their living mending pots and pans. Armand is good and kind and generous, but he idolizes the carefree hobo life. He speaks fondly of “the good old days of Paris” when a bell was rung in the marketplace as a signal to the hobos that they could pick up their scraps (15) and he extols the Court of Miracles, the beggars’ slum, as a place of feasting and merry-making (59).

But something is missing from Armand’s life, though it isn’t easy for him to admit. In one poignant scene, he is attending Midnight Mass on the Tournelle quay with the Calcet family and he tries to pray:

“In his misery he raised his eyes high over the altar—up to the stars in the Paris sky. ‘Please, God,’ he said, moving his lips soundlessly, ‘I've forgotten how to pray. All I know now is how to beg. So I'm begging you to find a roof for this homeless family‘” (88).

This scene is especially moving because from the very beginning Armand was presented with the cathedral in the background.

“Armand tramped under the black, leafless trees and around the cathedral by the river side without ever giving it a glance” (5).

Then he grins “like one of the roguish gargoyles on the cathedral” (7).

And now he is praying.

Before meeting the Calcet children, Armand was content with his small solitary world.

“The lights of Paris were floating in the river, but the only light in the tunnel flickered from a tiny fire Armand had made” (16).

Back then he sat under the bridge, a place lit only by his own little fire. He didn’t see the lights of Paris. He didn’t see the illuminated cathedral. Now he looks up to the stars. He looks up and he prays in the only way he knows how. And all because three little “starlings” have stolen his heart.

Just as Madame Calcet must learn to have less pride, Armand must learn to have more.

This delightful story is enlivened by Carlson’s endearing characters and rich description. The Calcets are winsome children. There’s Suzy, the eldest, determined to keep her family together, Paul who boasts of how he’d find his family a home if he were bigger, Evelyne, the littlest Calcet, and Jojo the dog who knows how to behave himself at mass.

Carlson’s portraits of hobos and gypsies reveal their kindness and generosity, their readiness to share what they have and help those even less fortunate than themselves. No one is perfect, but everyone is good. Armand hates work, but he shares his food with the children and Jojo. The gypsies are wanderers and thieves, but they shelter the homeless Calcet family and share Christmas with them.

The gypsies are described as colorful and wonderfully strange. Mireli is first seen in the square at Notre Dame offering to tell fortunes. She’s dressed in a blue scarf, flowered skirt, short fur coat, and tarnished silver sandals. Later the Calcet children meet Tinka, a gypsy girl with bangs and golden earrings. Tinka teaches Suzy about St. Sara and tells her of the gypsy's annual pilgrimage to Provence. But as exotic as they are, the gypsies have something important in common with the Calcets: They believe in sticking together too.

The Family Under the Bridge is a heartwarming tale that is as sweet as roasted chestnuts, as innocent as freshly-fallen snow, and as charming as little Suzy’s Christmas wish.

Joyeux Noël