What do you think?

Rate this book

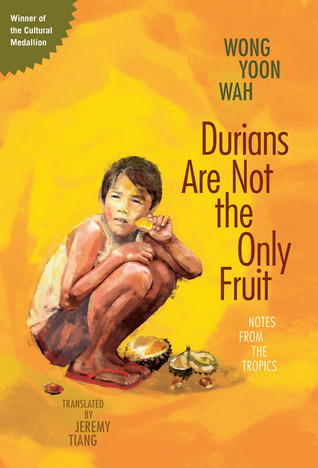

208 pages, Paperback

Published October 1, 2013

This illustrates the deep fault lines that run through Singaporean and Malaysian society. Even between two people of the same ethnicity, other markers such as education and language can present an insuperable boundary. It's easy to imagine how many divisions there are in countries which successive waves of immigration have filled a population diverse in any number of ways; harder to come up with ways of bridging these gaps.

Today, the surnames Wong or Ng tell you whether the possessor of the original name, whether Huang, Wang, or Wu, is Hakka, Cantonese or Hokkien. The early immigrants used their dialect groups as a means of organising themselves, so the British rulers paid a lot of attention to the political dimension of names and their divisions.

Many varieties of Chinese people means many varieties of Chinese literature, just as the Chinese have different faces - such as the Southeast Asian Chinese, whose facial features evolved in one generation to suit their new climate, turning a deeper brown beneath the year-round sun. In Singapore and Malaysia, I have only to look at someone's face to know whether they are English- or Chinese-educated, whether local or a recent immigrant from China. The Chinese will never be able to make themselves non-Chinese - their Chineseness will always be present in some form. Thus the complexity of what it means to be Chinese. The first time Singaporean or Malaysian Chinese visit China, they're always startled to discover how different they are from the Mainlanders.

Even the Western colonialists' imperialist, orientalist historical narrative contained a certain native mysticism. On 28 January 1819, the colonist and explorer Stamford Raffles sailed for the first time into Singapore River with his naval fleet. This would later be presented by the colonial powers are his 'discover' of Singapore, even though the island had already been developed into an important trading centre in the 14th century. No sooner had the British commandant, Major William Farquhar, landed with his troops, than his dog was eaten by a riverside crocodile, which was in turn shot dead by British guns. This was the beginning of the 'new world' that British historians would locate here. Even though this incident really happened, we cannot help receiving it as somewhat surreal, full of symbolism and exaggeration, a nonsense story. Yet the crocodile is a native of the land, and the British dog an accessory to the colonial powers, so its devouring could represent opposition to the foreign power, and the crocodile's subsequent demise the violent suppression of local resistance, followed by massacres, subjugation, invasion and finally, colonialism.

Although magical realism first attracted attention through its manifestation in South American writing, the Malayan rainforests in the colonial era, with their complicated political situation and boundaries, contained such surreal manifestations that the mystical became merely a part of everyday life. Even before encountering the external influences of magical realism, the observed world in this region was already bordering on hallucinatory: lions and lion-hearted fish emerging from the wilderness, able to roam the hills and waters, representing the desires of this island's inhabitants. When it comes to the plants of Nanyang, even the pitcher plant, a humble vine, eats meat for a living, able to capture its own insects or small rodents. And in the lakes and rivers of Southeast Asia, a species of fish is able to leap from the water to catch nearby frogs or small birds. When it rains, a fair few varieties of fish are able to walk on land. In Singapore, the more frequently seen are the common walking catfish and the forest walking catfish, though it is the snakehead that is most famous.

The European-style mansions and clubhouses, flooded with light, were like a child's version of paradise. After we had cycled past all that into the Chinese territories, the flat roads vanished altogether and we were back in a dark, primitive, world. The winding roads were full of potholes, full of mud and tree roots that resembled giant snakes. Our bicycles bounced over them, and frequently tumbled over into the ditch, dragging us with them. At the time, how I hated the dark Chinese territory, and longed for the brightness of our colonisers.

As an adult, when I remember this contrast, I can understand how the white people derived a sense of superiority, how they came to believe that colonialism brought culture and wealth, civilisation and light to the darkness of Nanyang. They wanted to rescue us from ignorance, poverty and backwardness. But we have grown up now and this is how we view this period: our colonisers stripped Nanyang of its natural resources, leaving behind only shady avenues, grand mansions and clubhouses.

In colonised countries, where the native people are pushed to the extremities, are neglected, even rejected, this ultimately gives them the space to develop resistance to hegemony, creating a language that encompasses many culture.