What do you think?

Rate this book

390 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1568

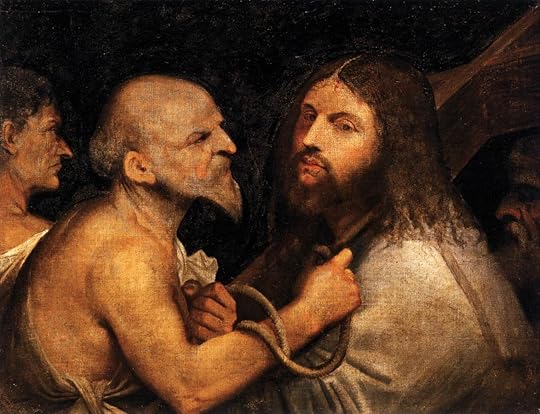

but this [sum] he consumed and squandered totally during his residence in Rome, where he lived without due care, as was his habit. Having completed the work assigned to him, he returned at once to Florence, where, being whimsical and eccentric, he occupied himself with commenting on a certain part of Dante, illustrating the Inferno and executing prints, over which he wasted much time; and neglecting his proper occupation, he did no work, and thereby caused infinite disorder in his affairs.Finally, each chapter is illustrated with a plate (unattributed). For Botticelli, we have this.

For different houses in various parts of [Florence], Sandro painted many pictures of a round form, with numerous figures of women undraped. Of these there are still two examples at Castello, a villa of the Duke Cosimo, one representing the birth of Venus, who is borne to earth by the Loves and Zephyrs: the second also representing the figure of Venus crowned with flowers by the Graces; she is here intended to denote the Spring, and the allegory is expressed by the painter with extraordinary grace.That’s it. But, not only is this description quite unlikely to convey anything useful to a reader about what the paintings actually look like, but the way the first sentence reads, it seems to imply that the pictures are of a “round form”; or at best it’s ambiguous.

An artist lives and acquires fame through his works; but with the passing of time, which consumes everything, these works—the first, then the second, and the third—fade away.

I have endeavored not only to record what the artists have done but to distinguish between the good, the better, and the best, and to note with some care the methods, manners, styles, behavior, and ideas of the painters and sculptors; I have tried as well as I know how to help people who cannot find out for themselves to understand the sources and origins of various styles, and the reasons for the improvement or decline of the arts at various times and among different people.