What do you think?

Rate this book

304 pages, Hardcover

First published March 6, 2014

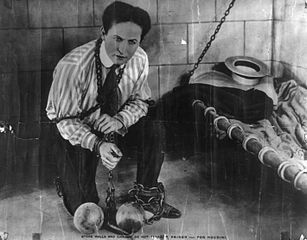

What no one knows, save for myself and one other person who likely died long ago, is that I didn’t just kill Harry Houdini. I killed him twice.Stephen Galloway, the award-winning author of The Cellist of Sarajevo, takes on a legendary real-life character and tries to make some magic with his lesser known history.

”Yours is a rare condition,” [the doctor] said, seeming almost excited, “in which the damage that is being done to your brain does not destroy cognitive function but instead affects your brain’s ability to store and process memories. In response to this, your brain will invent new memories.”So, Harry Houdini meets Memento?

“Houdini’s death has always really interested me. What would it be like to be the guy who punched Harry Houdini in the stomach?” from the Globe and Mail interviewThere are alternating tale-tellers in The Confabulist. Martin Strauss speaks for himself, and the Houdini chapters are told by an omniscient narrator. The time lines are dual as well, present day alternating with a past that advances from 1897, before Houdini had achieved world-wide renown, to 1927, as Martin recalls and we see for ourselves what transpired. We cover some real estate in The Confabulist, as well, from Canada to New York to sundry locales in Europe.

When asked how he landed on Houdini for his new novel, Galloway says he was fascinated by the showman’s iconic status, but also by the fact that Houdini himself was a sort of fiction. “Most magicians are kind of made-up characters, but him more than any. He’s a Hungarian Jew pretending to be Mr. America. Most of what he said about himself biographically was a total, total lie. So I just kind of arrived there and never left.” - from the Globe and Mail interviewStrauss’s history is far less interesting, but in his musings we get at some of the thematic issues of the novel. Some insight into international intelligence goings on of the period is also noteworthy.

How is it we can be so sure that we’ve seen, heard and experienced what we think we have? In a magic trick, the things you don’t see or think you see have a culmination, because at the end of the trick there’s an effect. Misdirection tampers with reconstruction. But if life works the same way, and I believe it does, then a percentage of our lives is a fiction. There’s no way to know whether anything we have seen or experienced is real or imaginedor

a memory isn’t a finished product, it’s a work in progressSo does Galloway succeed in making magic? Only somewhat. There are two issues I had with the book. One is the inherent difficulty of having an unreliable narrator. That this is done openly from the opening chapter does not make it any less problematic. How are we to know if what Strauss reports is true or imagined? And if one cannot know if what he reports is real, it makes for difficulty in relating to his experience, and knowing for ourselves that what we are reading is or is not an accurate rendering of events. The dimorphism between the wonderful tale of Houdini’s and the far less gripping tale of Martin Strauss makes one want to slip the knots of Martin’s chapters to make one’s way back to the real action. And, while the story of Houdini does succeed in holding our interest, it seemed to me that there remained a distance between reader and character, even for Houdini, that kept one from the sort of emotional engagement that is needed if we are to feel much for him. Martin is an obvious literary device, so one does not hope for too much there. But one does want to feel more of an investment in Houdini than was possible here.

confabulate (kənˈfæbjʊˌleɪt)

— vb

1. to talk together; converse; chat.

2. psychiatry to replace the gaps left by a disorder of the memory with imaginary remembered experiences consistently believed to be true.

In a magic trick, the things you don't see or think you see have a culmination, because at the end of the trick there's an effect. Misdirection tampers with reconstruction. But if life works the same way, and I believe it does, then a percentage of our lives is fiction. There's no way to know whether anything we've experienced is real or imagined.

We think that our minds are like a library -- the right book is there somewhere if you can find it. A whole story will then unfold with you as the narrator. But our memory changes, evolves, erases. Moments disappear and are replaced and combined. What's left of a person after they're gone is a spirit of who and what they were.

This is where our pain comes from. Because we know this is going to happen. We feel it and it underwrites our mourning.

For all of us the future is an unmade promise. For the living there is the present and the past. The past is always moving, always changing, as the people we lose are transformed in us. The past is no place to live. But it's the only place the dead lived.

Darkness has a way of making everything louder. There's no way to identify the sounds coming at you. You can imagine what they are, but it's always a guess, based on what you remember about the world before the light went out of it.

He'd always thought a theatre felt strange without people in it. With its seats empty, its lights up, and its air still, it reminded him of a dead body.