What do you think?

Rate this book

123 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1958

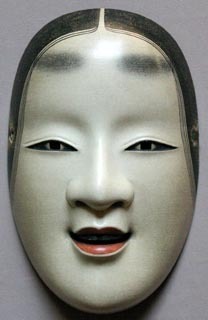

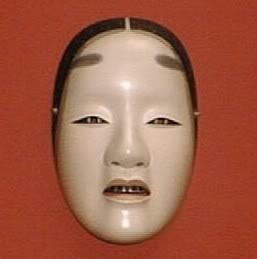

When you know the masks as well as we do, they come to seem like the faces of real women.

...A deeply inward kind of look. I think Japanese women long ago must have had that look. And it seems to me she must be one of the last women who lives that way still - like the masks - with her deepest energies turned inward.

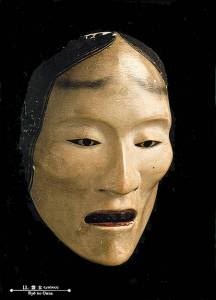

Just as there is an archetype of woman as the object of man's eternal love, so there must be an archetype of her as the object of his eternal fear, representing, perhaps, the shadow of his own evil actions.

"She has a peculiar power to move events in whatever direction she pleases, while she stays motionless. She's like a quiet mountain lake whose waters are rushing beneath the surface toward a waterfall. She's like the face on a No mask, wrapped in her own secret."