What do you think?

Rate this book

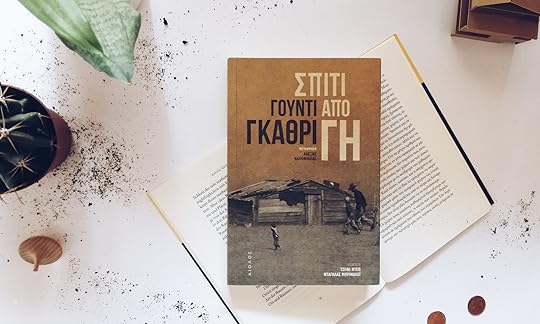

Finished in 1947 and lost to readers until now, House of Earth is legendary folk singer and American icon Woody Guthrie’s only finished novel. A powerful portrait of Dust Bowl America, it’s the story of an ordinary couple’s dreams of a better life and their search for love and meaning in a corrupt world.

Tike and Ella May Hamlin are struggling to plant roots in the arid land of the Texas panhandle. The husband and wife live in a precarious wooden farm shack, but Tike yearns for a sturdy house that will protect them from the treacherous elements. Thanks to a five-cent government pamphlet, Tike has the know-how to build a simple adobe dwelling, a structure made from the land itself—fireproof, windproof, Dust Bowl-proof. A house of earth.

A story of rural realism and progressive activism, and in many ways a companion piece to Guthrie’s folk anthem “This Land Is Your Land,” House of Earth is a searing portrait of hardship and hope set against a ravaged landscape. Combining the moral urgency and narrative drive of John Steinbeck with the erotic frankness of D. H. Lawrence, here is a powerful tale of America from one of our greatest artists.

An essay by bestselling historian Douglas Brinkley and Johnny Depp introduce House of Earth, the inaugural title in Depp’s imprint at HarperCollins, Infinitum Nihil.

290 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2013

“On the fourteenth day of April,

Of nineteen thirty-five,

There struck the worst of dust storms

That ever filled the sky.

You could see that dust storm coming

It looked so awful black,

And through our little city,

It left a dreadful track.”

It was a clear day. A blue sky. A few puffy, white-looking thunderclouds dragged their shadows like dark sheets across the flat Cap Rock country. The Cap Rock is that big high, crooked cliff of limestone, sandrock, marble, and flint that divides the lower west Texas plains from the upper north panhandle plains. The canyons, dry wash rivers, sandy creek beds, ditches, and gullies that joined up with the Cap Rock cliff form the graveyard of past Indian civilizations, flying and testing grounds of herds of leather-winged bats, drying grounds of monster-size bones and teeth, roosting, nesting, and the breeding place of the bald-headed big brown eagle. Dens of rattlesnakes, lizards, scorpions, spiders, jackrabbit, cottontail, ants, horny butterfly, horned toad, and stinging winds and seasons. These things all were born of the Cap Rock cliff and it was alive and moving with all these and with the mummy skeletons of early settlers of all colors. A world close to the sun, closer to the wind, the cloudbursts, floods, gumbo muds, the dry and dusty things that lose their footing in this world, and blow, and roll, jump wire fences, like the tumbleweed, and take their last earthly leap in the north wind out and down, off the upper north plains, and down onto the sandier cotton plains that commence to take shape west of Clarendon.”

“Let them? We caused ’em to steal?”

“Yes. We caused them to steal. Penny at a time. Nickel at a time. Dime. A quarter. A dollar. We were easygoing. We were good-natured. We didn’t want money just for the sake of having money. We didn’t want other folks’ money if it meant that they had to do without. We smiled across their counters a penny at a time. We smiled in through their cages a nickel at a time. We handed a quarter out our front door. We handed them money along the street. We signed our names on their old papers. We didn’t want money, so we didn’t steal money, and we spoiled them, we petted them, and we humored them. We let them steal from us. We knew that they were hooking us. We knew it. We knew when they cheated us out of every single little red cent. We knew. We knew when they jacked up their prices. We knew when they cut down on the price of our work. We knew that. We knew they were stealing. We taught them to steal. We let them. We let them think that they could cheat us because we are just plain old common everyday people. They got the habit.”

“They really got the habit,” Tike said.

“Like dope. Like whiskey. Like tobacco. Like snuff. Like morphine or opium or old smoke of some kind. They got the regular habit of taking us for damned old silly fools,” she said.”

“The picture of her face, her eyelids, hair, forehead, ears, cheeks, chin, was one of almost complete peace and comfort. Tike saw a trace, a tiny trace, but a trace of ache, pain, and misery there as she licked her lips and breathed. A feeling came over him. A feeling that had always come over him when he saw her look this way. It was a feeling of love, yet a feeling of fight. A love that was made out of fight, the fight that he would fight if any living human hurt or harmed or even spoke low-down or bad words about his Lady. And for a good long time he seemed to get a higher view, somehow, of their life together, their life on this gumbo land in this shack, and even the land and the shack and their cowshed he felt did not really belong to them. No. It all belonged to a man that had never set foot on it. Belonged to somebody that did not give a damn about it. Belonged to someone that didn’t care about the feelings of their cowshed. Somebody somewhere that did not know the fiery seeds of words and of tears and of passions, hopes, split here on this one spot of the earth. Belonged to somebody who did not think that these people were able to think. Belonged to somebody who had their names wrote down on his money list, his sucker list. Belonged to somebody who does not know how quick we can get together and just how and just fast we can fight. Belongs to a man or a woman somewhere that don’t even know that we’re down here alive. It belongs to a disease that is the worst cancer on the face of this country, and that cancer goes hand in hand with Ku Klux, Jim Crow, and the doctrine and the gospel of race hate, and that disease is the system of slavery known as sharecropping.”

“A thousand and one things came back into his mind, things that he ought to be doing, working at, fixing up, getting ready for. His brain commenced to show up moving pictures of all of the jobs he had started, the ones that he had finished, and the ones that had to be started right away. This. That. And the other thing. “This, that, and something else. All of this work, all of these jobs, all of this sweat and good labor poured into a useless bucket and down a senseless drain on a piece of land that did not belong to him, did not shelter Ella May, did not keep them away from the germs, the filth, the misery, did not keep their hides from the heat nor the cold, did not look good to their eyes, and by the law of the land they could not lift a hand to build the place into that nicer one because the man that owned it did not care about all of this. Oh. These. These things. And then a lot of other things came and went, roared and buzzed around in his brain. He tried to dream up some earthly scheme to get his hands on a piece of good farmland to raise up that house of earth on. Ohh. Yes. That Department of Agriculture book was an awful mighty good thing, laying there at her elbow on that hay. But it made their biggest misery even bigger, and their biggest dream even plainer, and their biggest craving ten times more to be craved. A fireproof, windproof, dirt-proof, bug-proof, thief-proof house of earth”

“This was the vast and undying beauty, the dynamic and eternal attraction, the lure, the bait, the magnetic pull that, in addition to their blood kin and salty love for the wide open spaces and their lifetime bond to and worship of the land, caused not only Ella May and Tike Hamlin but hundreds of thousands and millions and millions of other folks just about like them to scatter their seeds, their words, and their loves so freely here.”

“One year. And what is a year? A year is something that can be added on, but it can never be taken away. Yes, added on, earmarked and tagged, counted in signs of dollars and cents, written down the income column and across the page with names, and photos can be taken of faces and clipped onto the papers, and the prints of the new baby’s feet can be stamped on the papers of the birth, and the print of the thumb going back to work can be stamped onto the papers that say it is a good place to work. And a year is work. A year is that nervous craving to do your good job and to draw down your good pay, and to join your good union.

And a year of work is three hundred and sixty-four, or -five, or -six days of the run, the hurry, the walking, the bouncing, and the jumping up and down, the arguments, fights, the liquor brawls, hangovers, headaches, and all. Work takes in all climates, all things, all rooms, all furrows, all streets, all sidewalks, and all the shoes that tramp on them. The whirl and roll of planets do not make a year a year, nor the breath of the trifling wind, changing from cold to hot, forming steam back into ice. Oceans of waters that flow down from the tops of the Smokies and roll in the sea, they help some to make a year a year, but they don’t make the year.

Tike had said to Ella May once before they were married, “What a year is, is just another round in our big old fight against the whole world.” What he meant was his fight against the weather and against other men, and sometimes against his own self. But in his own words he was very close to right. He had a right, in a way, to say, “Our fight against the whole world,” because it had always looked to him that his little bunch of people out there on the upper plains were fighting against just about everything in the world. He did not mean that, I, Tike Hamlin, am fighting against the world and all that is in it.....

.....And so the year went around. The wheel of time rolled down the road of troubles. They had the same things hit them day after day. The same cows bawled to be milked every sunset, and bawled to be milked again at every sunrise.”