What do you think?

Rate this book

252 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2013

Read by Paul English and Heather Bolton

Read by Paul English and Heather Bolton Do big names phone-it-in? Sure felt as if Keneally did just that with this one. Shame and the Captives lacked both spark and enthusiasm, however I did learn a lot by engaging with this book as it sent me scurrying to the interwebz to look up the gen.

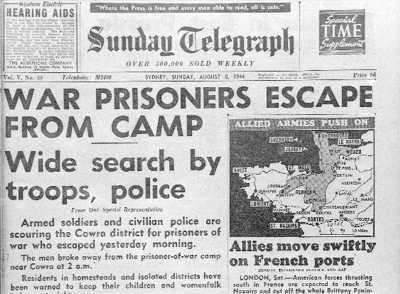

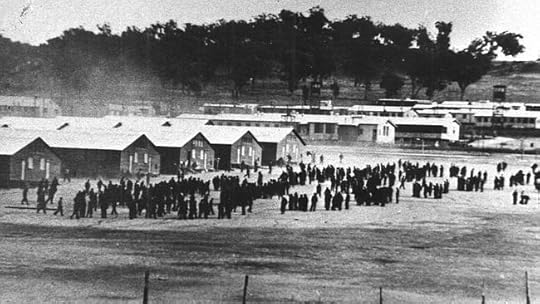

Do big names phone-it-in? Sure felt as if Keneally did just that with this one. Shame and the Captives lacked both spark and enthusiasm, however I did learn a lot by engaging with this book as it sent me scurrying to the interwebz to look up the gen. the prisoner of war camp at Cowra, NSW, where hundreds of Japanese were killed in a mass breakout in 1944.

the prisoner of war camp at Cowra, NSW, where hundreds of Japanese were killed in a mass breakout in 1944.