What do you think?

Rate this book

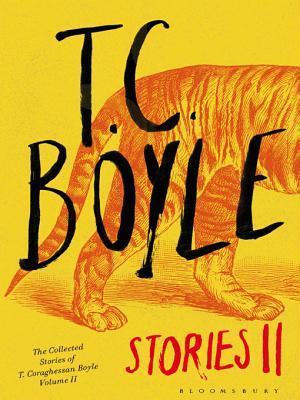

945 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2013

'I looked down at my feet. a woman was clutching my right leg to her as if she’d given birth to it, her eyes as loopy as any crack-head’s. My left leg was in the grip of a balding guy who might have been a clerk in a hardware store and he was looking up at me like a toad I’d just squashed. "Jesus," they hissed. "Jesus!"'

'She wanted to agree with him, wanted to say that she didn’t care about radiation or anything else because we all have to die and the sooner the better, that all she cared about was the peace of the forest and her home where she’d buried her husband fourteen years ago, but she was afraid despite herself. She pictured rats with five legs, birds without wings, her own self sprouting a long furred tail beneath her skirts while the meat shone in the pan as if it were lit from within. The night deepened. Leonid huffed for air. She hurried on.'

'They wore each other like a pair of socks. He was at her house, she was at his. Everywhere they went—to the mall, to the game, to movies and shops and the classes that structured their days like a new kind of chronology—their fingers were entwined, their shoulders touching, their hips joined in the slow triumphant sashay of love.'

'They were together at his house one night when the rain froze on the streets and sheathed the trees in glass.'

'“Do you love me?” she whispered. There was a long hesitation, a pause you could have poured all the affirmation of the world into. “Yes,” he said finally, his voice so soft and reluctant it was like the last gasp of a dying old man.'

The chief themes of 'Stories II', which collects all the stories Boyle has published since 1990 as well as fourteen new ones, are similar to those of his more recent novels, and the environmentalist and naturalist strains he explored in 'Friend of the Earth', 'Drop City' and 2011's 'When the Killing's Done' crop up frequently again here. For example one story concerns a rancher on the Latin American Pampas who refuses to see that his animals are being blinded by the hole in the ozone layer above his land, another story has a subplot about the decimation of American bird populations as a consequence of the exploding stray and domestic cat populations (a very real problem). Boyle stories are also frequently set in isolated communities and the dichotomy of wildness and civilisation comes into play several times. This is most obvious with the novella 'Wild Child', a tour de force of historical fiction writing which tells the story of a feral child discovered in the countryside in revolutionary France and brought to Paris for scientific study. The novella arrives two thirds of the way through 'Stories II' (which clocks in around 900 pages) and offers a welcome change of pace, it is powerful, evocative (the atmosphere reminded me of Andrew Miller's excellent 'Pure') and utterly gripping, the kind of story that never leaves you and one of many genuine treasures to be found amongst the curios and lesser works on show here.

The chief themes of 'Stories II', which collects all the stories Boyle has published since 1990 as well as fourteen new ones, are similar to those of his more recent novels, and the environmentalist and naturalist strains he explored in 'Friend of the Earth', 'Drop City' and 2011's 'When the Killing's Done' crop up frequently again here. For example one story concerns a rancher on the Latin American Pampas who refuses to see that his animals are being blinded by the hole in the ozone layer above his land, another story has a subplot about the decimation of American bird populations as a consequence of the exploding stray and domestic cat populations (a very real problem). Boyle stories are also frequently set in isolated communities and the dichotomy of wildness and civilisation comes into play several times. This is most obvious with the novella 'Wild Child', a tour de force of historical fiction writing which tells the story of a feral child discovered in the countryside in revolutionary France and brought to Paris for scientific study. The novella arrives two thirds of the way through 'Stories II' (which clocks in around 900 pages) and offers a welcome change of pace, it is powerful, evocative (the atmosphere reminded me of Andrew Miller's excellent 'Pure') and utterly gripping, the kind of story that never leaves you and one of many genuine treasures to be found amongst the curios and lesser works on show here.

'Have you heard of Tunguska? In Russia? This was the site of the last-known large-body impact on the Earth’s surface, nearly a hundred years ago. Or that’s not strictly accurate—the meteor, an estimated sixty yards across, never actually touched down. The force of its entry— the compression and superheating of the air beneath it—caused it to explode some twenty-five thousand feet above the ground, but then the term “explode” hardly does justice to the event. There was a detonation—a flash, a thunderclap— equal to the explosive power of eight hundred Hiroshima bombs. Thirty miles away, reindeer in their loping herds were struck dead by the blast wave, and the clothes of a hunter another thirty miles beyond that burst into flame even as he was

poleaxed to the ground. Seven hundred square miles of Siberian forest were leveled in an instant. If the meteor had hit only four hours later it would have exploded over St. Petersburg and annihilated every living thing in that glorious and baroque city.'

'When it comes, the meteor will punch through the atmosphere and strike the Earth in the space of a single second, vaporizing on impact and creating a fireball several miles wide that will in that moment achieve temperatures of 60,000 degrees Kelvin, or ten times the surface reading of the sun. If it is Chicxulub-sized and it hits one of our landmasses, some two hundred thousand cubic kilometers of the Earth’s surface will be thrust up into the atmosphere, even as the thermal radiation of the blast sets fire to the planet’s cities and forests. This will be succeeded by seismic and volcanic activity on a scale unknown in human history, and then the dark night of cosmic winter. If it should land in the sea, as the Chicxulub meteor did, it would spew superheated water into the atmosphere instead, extinguishing the light of the sun and triggering the same scenario of seismic catastrophe and eternal winter, while simultaneously sending out a rippling ring of water three miles high to rock the continents as if they were saucers in a dishpan. So what does it matter? What does anything matter? We are powerless. We are bereft. and the gods—all the gods of all the ages combined—are nothing but a rumor.'

(Copyright Viking Press, 2013)