Though promoted as a novel about The Rapture or a Rapture-like event, fifty pages in you realize The Leftovers isn’t. Tom Perrotta’s novel is about human reactions to tragedy. We don’t know why millions of people disappeared, can’t recognize a methodology or pattern to the mass disappearances, and spend none of the book pursuing answers. Perrotta tells us multiple times that no one can figure it out. Sorry, world: you just lose, and now your citizens deal with it.

We go to inspirational speeches, grief counseling and A.A. We hit the bottle, seek out any company we can get, and watch obscene amounts of talk-TV. We get a mother walking fugally through her empty house and writing a journal to the son who no longer exists. Marriages break up and cities tremble.

We follow a handful of people trying to make sense of their own lives in the wake of civilization’s shake-up. It’s not quite an apocalypse (The Rapture wouldn’t be, right?), but things can’t quite go back to being the same. Faithful priests left behind seek to comfort others while questioning what they did wrong; parents grieve for children whose bodies aren’t even left to bury; characters hit the road, or form sexually-liberated support groups, or simply linger. This book doesn’t push the plot forward with every page. It shouldn’t, and it exposes how shortsighted that rule is, for a book about not knowing what to do must necessarily revel in stalling out.

The analogs to real life are refreshingly distinct. When the event is largely called “October 14th,” it’s hard not to think “9/11.” Perrotta eventually tackles the parallels in exposition, yet the lack of a single image or video to capture what happened, and the lack of villains to blame, turn October 14th and its “Sudden Departure” into something ultimately far more frustrating. It’s equal parts existential crisis and tragedy.

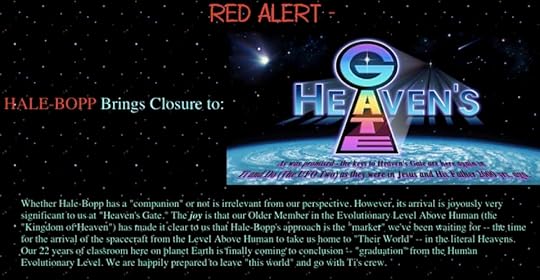

The religious horror spawns an analog of the Westboro Baptist Church, the “Guilty Remnant,” a cult of people who swear vows of silence and mill around public areas to remind everyone what happened. Where it could be generic anti-Westboro fiction, Perrotta instead depicts them as some of the saddest people, and introduces the group through the lens of a husband whose wife is in that hushed crowd, having seemingly shed her gross depression for this zeal. That she’s lost so much weight, has resumed smoking and has the vigor from earlier in her life presents a more dynamic portrait of a human being than any fiction that directly tackles Westboro-like groups, and frankly, presents more dimensionality than the Westboro protestors themselves.

Religion gets its stage time, as it ought to in a book using a Rapture-gimmick. Yet we use an interesting lens to see inside the fundamentalist cult: a mother who’s lost her children joins as much out of malaise as the persistence of the priest. When she becomes a Watcher, designated to essentially stalk people of suspected high-sinfulness, she pursues it for gossipy entertainment, is often bored or uneasy, and has mundane thoughts like craving chocolate or to avoid the smoking the cult insists upon. We get the typical application of religion-as-coping-mechanism, but also see it as more nuanced, in just how an individual could cope through ritual and dogma, and how in some ways it simply fails. We also see how it makes our regular world seem strange; there’s a particular double-edged humor to her shock that a Safeway has four shelves devoted to barbecue sauce.

The Leftovers features an increasingly popular form of loose narrative. You’re seldom brought into the moment; chapters open with a recap of recent events, and tend to progress by recapping what happened next, and next, and so-on, focusing in on a few conversations or particular events for a page or less. This makes the bulk of the book expository. I like the style; it worked in ancient myths, in formative histories, and still works when we tell each other about our days. Perrotta makes it work by keeping most of his exposition novel, glossing over the details we can guess. The beginning is particularly strong, as recapping the October 14th tragedy feels not just valid, but a little like newscasting reportage. Yet for a book that follows specific characters over long journeys of self-discovery, there are readers who will want it to be more focused on what they actually did, and to be brought into the moment page after page.

Only after the fact did I learn this was labeled the “comic novel.” I’m still uneasy with this label, and don’t wholly comprehend what it’s supposed to mean. The Leftovers, like virtually all “comic novels” I’ve read, isn’t particularly funny and never made me laugh, but I don’t know if that’s what critics intend by the label. It has its brightness, and there are some questionable things, but is a cult smoking because they acknowledge their lives are finite really comical? It could be played that way. Perrotta doesn’t seem to play it up for humor. Perhaps that’s the difference between the old literary establishment and the new one; comedy, and Twain, and Swift, and the art of actually being funny may be unfashionable. I hold none of this against Perrotta, who delivered a consummate job on his novel. In interviews he’s even conceded that this was originally a more humorous project than it became as he wrote it. Rather than a slight against the author, it’s simply a curiosity with publishers and critics.