What do you think?

Rate this book

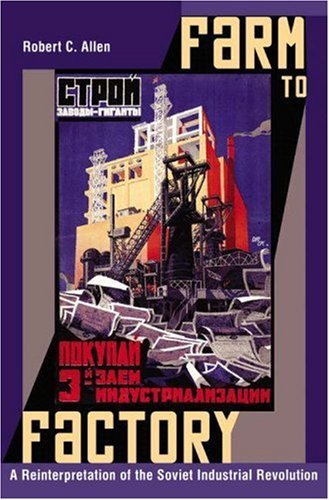

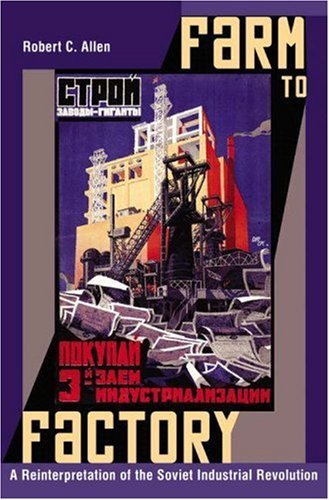

312 pages, Hardcover

First published September 29, 2003

Perhaps the greatest virtue of the market economy is that no single individual is in charge of the economy, so no one has to contrive solutions to the challenges that continually arise. The early strength of the Soviet system became its great weakness as the economy stopped growing because of the failure of imagination at the top.