What do you think?

Rate this book

At Tuppenny-hapenny Cottage in the English countryside, five elderly people live together in rancorous disharmony. Adela Bastable bosses the house, as her brother Bernard passes his days thinking up malicious schemes against the baby-talking Marigold and secret drinker Shorty, while kindly George lies bedridden upstairs. The mismatched quintet keep their spirits alive by bickering and waiting for grandchildren to visit at Christmas. But the festive season does not herald goodwill to all at Tuppenny-hapenny Cottage. Disaster and chaos, it seems, are just around the corner ...

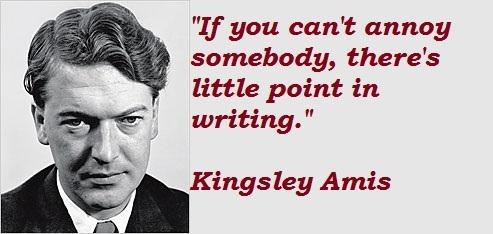

Told with Amis's piercing wit and humanity, Ending Up (1974) is a wickedly funny black comedy of the indignities of old age.

With a new introduction by Helen Dunmore.

132 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 1974

Bernard had hung back. He had glimpsed the Fishwicks' car while the door was open and felt wrath stirring. All cars displeased him, and not just for superficial reasons like the noise they made or their tendency to be painted bright colours. They were like horses as seen by a foot soldier: damned nuisances, much too much fuss made about them, needing constant attention, ridiculous that grown men should be reduced to depending on them. This particular car was outstandingly objectionable. It was larger and newer than the one he had at any rate a financial stake in; far more galling, it belonged to someone of twenty-five or thirty or whatever it was. The youngster seemed to think he had a perfect right to buy it and stuff it with petrol and oil and drive it all over the place just as he felt inclined. (p. 23)

Shorty was doing his best to read a paperback book that told, it seemed to him, of some men on a wartime mission to blow something up. His state of mind, normal for him at this time of day, lent the narrative an air of deep mystery. New characters kept on making unceremonious appearances, or, more exactly, he would find that he had been in a sense following their activities for several pages without having noticed their arrival, or, more exactly still, they would turn out, on consultation of the first couple of chapters, to have been about the place from the start. The prose style was tortuous, elliptic, allusive, full of strange poeticisms; the dialogue, after the same fashion, was stuffed with obscurities and non-sequiturs and, like the story itself, constantly referred to people, events, places and the rest that had never come up before, or once again, had come up eight or eighty pages earlier. Every so often he would run across some detail that nearly convinced him he had read the whole thing before, perhaps more than once. But none of that bothered him in the least: he was not working for an exam, and to read as he did meant that he used up books very slowly and economically. (p. 54-55).