What do you think?

Rate this book

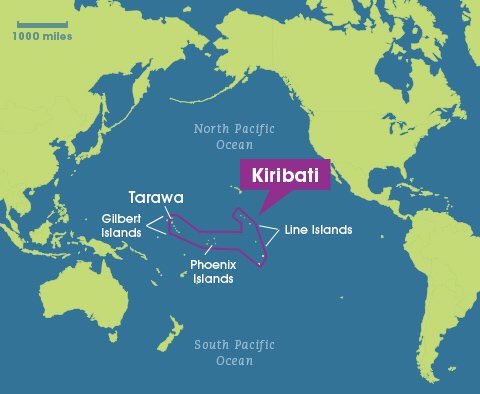

Fantasized about quitting the 9-5? Walking away from credit card debt and student loans? Think living in the South Pacific for two years sounds like a perfect solution and perhaps even a winning idea for your first novel? Maarten Troost does just that, setting up as a devil-may-care islander while his girlfriend, Sylvia, gets to work on saving the planet, or at least a little part of it on an end-of-the-world atoll, Tarawa.

Life on Tarawa resembles not so much paradise as a theatre of the absurd where planes fly with the aid of masking tape, Coconut Stalinism prevails as national government and Sylvia is co-opted by the CIA to spy on the Chinese. But abandoning continental hang-ups like barbequeing the local dogs and watching on as international industrial fishing trawlers plunder the world's richest tuna supply aren't so easy. Perhaps only by following the locals and letting go, one just might find a better way to live...

162 pages, Kindle Edition

First published June 8, 2003

(Tiabo) You must tell me which song, in your opinion, do you find to be the most offensive.”

“What?” she asked wearily.

“I want you to tell me which song is so terrible that the I-Kiribati will cover their ears and beg me to turn it off.”

“You are a strange I-Matang.”

I popped in the Beastie Boys’ Check Your Head. I forwarded it to the song “Gratitude,” which is an abrasive and highly aggressive song.

“What do think?” I yelled.

“I like it.”

Damn. I moved on to Nirvana’s Lithium. I was sure that grunge-metal-punk would not find a happy audience on an equatorial atoll.

“It’s very good,” Tiabo said.

Now I was stumped. I tried a different tack. I inserted Rachmaninoff.

“I don’t like this,” Tiabo said.

Now we were getting somewhere.

“Okay, Tiabo. How about this?” We listened to a few minutes of La Bohème. Even I felt a little discombobulated listening to an opera on Tarawa.

“That’s very bad,” Tiabo said.

“Why?”

“I-Kiribati people like fast music. This is too slow and the singing is very bad.”

“Good, good. How about this?” I played Kind of Blue by Miles Davis.

“That’s terrible. Ugh . . . stop it.”

Tiabo covered her ears.

Bingo. I moved the speakers to the open door.

“What are you doing?” Tiabo asked.

I turned up the volume. For ten glorious minutes, Tarawa was bathed in the melancholic sounds of Miles Davis. Tiabo stood shocked. Her eyes were closed. Her fingers plugged her ears. I had high hopes that the entire neighborhood was doing likewise. Finally, I turned it off. I listened to the breakers. I heard the rustling of the palm fronds. A pig squealed. But I did not hear “La Macarena.” Victory.

“Thank you, Tiabo. That was wonderful.”

"[Airan, a young Australian-educated employee of the Bank of Kiribati] was, however, miserable. He had just been promoted to assistant manager.This system is why many governmental Kiribati positions remain in I-Matang hands. "Sylvia's presence ensured that the organization would not crumble under the demands of bubuti system, which is exactly what occurred when the only other international nongovernmental organization to work in Kiribati decided to localize. Its project funds were soon gobbled up in a flurry of bubutis and the organization dissolved."

"This is very bad," he said.

"Why?" I asked. "That's excellent news."

"No. People will come to me with bubuti. They will bubuti me for money. They will bubuti me for jobs. It is very difficult."