What do you think?

Rate this book

552 pages, Hardcover

First published August 30, 2011

The physical symptoms of starvation, suffered in varying combinations by the large majority of Leningraders, were emaciation, dropsical swelling of the legs and face, skin discoloration (“hunger tan” in the slang of the time – faces are described as turning “black,” “blue-black,” “yellow” or “green”), ulcers, loosening or loss of teeth and weakening of the heart. Women stopped menstruating and sexual desire vanished.

Within the city, institutions involved in food processing and distribution were ordered to search their premises for forgotten or defective stocks that could substitute for conventional flours in the production of bread. At the mills, flour dust was scraped from walls and from under floorboards; breweries came up with 8,000 tons of malt, and the army with oats previously destined for its horses. (The horses were instead fed with birch twigs soaked in hot water and sprinkled with salt. Another feed, involving compressed peat shavings and bonemeal, they rejected). Grain barges sunk by bombing off Osinovets were salvaged by naval divers, and the rescued grain, which had begun to sprout, dried and milled… At the docks, large quantities of cotton-seed cake, usually burned in ships’ furnaces, were discovered. Though poisonous in its raw state, its toxins were found to break down at high temperatures, and it too went into bread.

The Führer is determined to erase the city of Petersburg from the face of the earth. After the defeat of Soviet Russia there can be no interest in the continued existence of this large urban centre. Finland has likewise shown no interest in the maintenance of the city immediately on its new border.Reid’s central focus is on the months of mass death by starvation and freezing during the first winter - the unusual harsh winter of 1941-42. Vividly she depicts daily life – or actually death – under the siege.

It is intended to encircle the city and level it to the ground by means of artillery bombardment using every calibre of shell, and continual bombing from the air.

Following the city’s encirclement, requests for surrender negotiations shall be denied, since the problem of relocating and feeding the population cannot and should not be solved by us. In this war for our very existence, we can have no interest in maintaining even a part of this very large urban population.

Over the course of three months, the city changed from something quite familiar — in outward appearance not unlike London during the Blitz — to a Goya-esque charnel house, with buildings burning unattended for days and emaciated corpses littering the streets. For individuals the accelerating downward spiral was from relatively ‘normal’ wartime life — disruption, shortages, air raids — to helpless witness of the death by starvation of husbands, wives, fathers, mothers and children — and for many, of course, to death itself.The first hand testimonials Reid quotes and comments convey the horror in an often eloquent way; the book brims with harrowing and detailed descriptions about the mass graves, the corpses dragged on sledges through the frozen streets, the struggle to survive, the rationing system, the hunt for food, the mental state of the citizens trapped in hell, eating pets and wallpaper glue, desperately cooking leather belts or an extract of fermented birch sawdust, hoping it to turn into soup. The food obsession, the excruciating starvation process, euphemistically called ‘dystrophy’ , a pseudo-medical term, the despair and grief for the dead - the staggering facts and figures are piercing and bewilder.

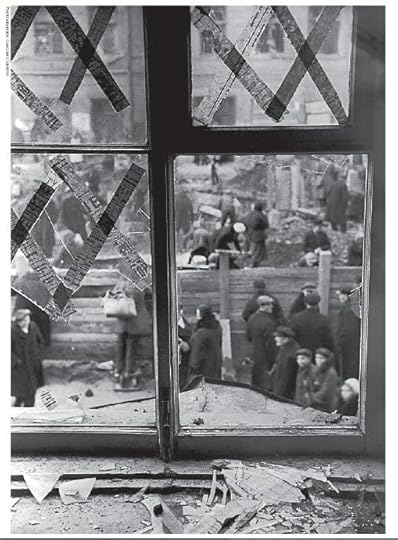

"...Immediately pre-war, the city had a population of just over three million. In the twelve weeks to mid- September 1941, when the German and Finnish armies cut it off from the rest of the Soviet Union, about half a million Leningraders were drafted or evacuated, leaving just over 2.5 million civilians, at least 400,000 of them children, trapped within the city. Hunger set in almost immediately, and in October police began to report the appearance of emaciated corpses on the streets. Deaths quadrupled in December, peaking in January and February at 100,000 per month. By the end of what was even by Russian standards a savage winter – on some days temperatures dropped to -30°C or below – cold and hunger had taken somewhere around half a million lives. It is on these months of mass death – what Russian historians call the ‘heroic period’ of the siege – that this book concentrates. The following two siege winters were less deadly, thanks to there being fewer mouths left to feed, and to food deliveries across Lake Ladoga, the inland sea to Leningrad’s east whose south-eastern shores the Red Army continued to hold. In January 1943 fighting also cleared a fragile land corridor out of the city, through which the Soviets were able to build a railway line. Mortality nonetheless remained high, taking the total death toll to somewhere between 700,000 and 800,000 – one in every three or four of the immediate pre-siege population – by January 1944, when the Wehrmacht finally began its long retreat to Berlin..."Bomb damage, September 1941:

"The first rule of foreign policy, the dinner-party truism has it, is never to invade Russia. Why did Hitler, very conscious of the disaster that befell Napoleon there, decide to attack the Soviet Union?October 1941: courtyard of the Young People’s Theatre, after shelling:

His aims, from the campaign’s inception in 1940, were not those of conventional geopolitics. He did not want just to annexe useful territory and create a new balance of power, but to wipe out a culture and an ideology, if necessary a race. His vision for the newly conquered territories, as expounded over meals at his various wartime headquarters, was of a thousand-mile-wide Reich stretching from Berlin to Archangel on the White Sea and Astrakhan on the Caspian. ‘The whole area’, he harangued his architect Albert Speer, must cease to be Asiatic steppe, it must be Europeanized! The Reich peasants will live on handsome, spacious farms; the German authorities in marvellous buildings, the governors in palaces. Around each town there will be a belt of delightful villages, 30–40km deep, connected by the best roads. What exists beyond that will be another world, in which we mean to let the Russians live as they like.12

Existing cities were to be stripped of their valuables and destroyed (Moscow was to be replaced with an artificial lake), and the delightful new villages populated with Aryan settlers imported from Scandinavia and America. Within twenty years, Hitler dreamed, they would number twenty million. Russians – lowest of the Slavs – were to be deported to Siberia, reduced to serfdom, or simply exterminated, like the native tribes of America. Putting down any lingering Russian resistance would serve merely as sporting exercise. ‘Every few years’, Speer remembered, ‘Hitler planned to lead a small campaign beyond the Urals, so as to demonstrate the authority of the Reich and keep the military preparedness of the German army at a high level.’ As a later SS planning document put it, the Reich’s ever-mobile eastern marches, like the British Raj’s North-West Frontier, would ‘keep Germany young’..."

"...In winter, lying in bed, I thought of one thing until my head hurt: there, on the shelves in the shops, there had been canned fish. Why hadn’t I bought it? Why had I bought only eleven jars of cod-liver oil, and not gone to the chemist’s a fifth time to get another three? Why hadn’t I bought a few vitamin C and glucose tablets? These ‘whys’ were terribly tormenting.Reid writes of the failure of Stalin's government to evacuate the city before the siege began:

I thought of every uneaten bowl of soup, every crust of bread thrown away, every potato peeling, with as much remorse and despair as if I’d been the murderer of my own children. But all the same, we did as much as we could, and believed none of the reassuring announcements on the radio..."

"Failing to empty Leningrad of its surplus population before the siege ring closed was one of the Soviet regime’s worst blunders of the war, leading to more civilian deaths than any other save the failure to anticipate Barbarossa itself. By the time the last train left, on 29 August, 636,283 people, according to official sources, had been evacuated from Leningrad. (This compares with 660,000 civilians evacuated from London in only a few days on Britain’s declaration of war two years earlier.) Excluding refugees from the Baltics and elsewhere who passed through the city, the number falls to 400,000 at best. Just over two and a half million civilians were left behind in the city, plus another 343,000 in the surrounding towns and villages within the siege ring. Over 400,000 of them were children, and over 700,000 other non-working dependants..."Scavenging meat from a horse killed by shelling. Date unknown:

"...Also celebrated as a manifestation of the defiant Leningrad spirit is the fact that some of its dozens of theatres and concert halls continued to function. The Musical Comedy Theatre – the Muzkomediya – stayed open almost throughout the winter, and concerts continued to be held under the crystal-less chandeliers of the Philharmonia into December. (Of the string players, an audience member noted, only the double bassists could wear sheepskin coats. The rest wore padded cotton jackets, which allowed freer movement of the arms.)As the siege prolonged, and the winter got colder, desperate times set in. Ordinary citizens and even soldiers and officers of the Red Army were forced to resort to cannibalism:

It is claimed that altogether, Leningraders enjoyed over twenty-five thousand public performances of different kinds in the course of the blockade, and the image of artists flinging themselves into war work – Shostakovich on the roof of the Conservatoire, Akhmatova standing guard duty outside the Sheremetyev Palace, prima ballerinas sewing camouflage nets – is one of the key tropes of the siege..."

"Like Leningrad’s starving civilians, some soldiers resorted to cannibalism. Hockenjos came across what he called a ‘man-eaters’ camp’ in the woods behind Zvanka, the stripped limbs confirming the statements of two young Red Army nurses who had been taken prisoner and given jobs in his battalion’s field hospital...Leningrad: The Epic Siege of World War II, 1941-1944 was an excellent book. Author Anna Reid did an incredible job putting this work together. It was exceptionally well researched, formatted, written, and delivered.

...‘One day’, Yershov relates, Sergeant Lagun noticed that an army doctor, Captain Chepurniy, was digging in the snow in the yard. Covertly watching, the sergeant saw him cut a piece of flesh from an amputated leg, put it in his pocket, re-bury the leg in the snow and walk away. Half an hour later Lagun walked into Chepurniy’s room as if he had something to ask him, and saw that he was eating meat out of a frying pan. The sergeant was convinced that it was human flesh . . . So he raised the alarm and in the course of the ensuing investigation it became clear that not only were the hospital’s sick and wounded eating human flesh, but so too were about twenty medical personnel, from doctors and nurses to outdoor workers – systematically feeding on dead bodies and amputated legs.

They were all shot on a special order of the Military Council...

...Overall, 64 per cent of those arrested for ‘use of human meat as food’ were female, 44 per cent unemployed or ‘without fixed occupation’ and over 90 per cent illiterate or in possession of only basic education. Only 15 per cent were ‘rooted inhabitants’ of Leningrad and only 2 per cent had a criminal record.37 The typical Leningrad ‘cannibal’, therefore, was neither the Sweeney Todd of legend nor the bestial lowlife of Soviet history writing, but an honest, workingclass housewife from the provinces, scavenging protein to save her family..."