What do you think?

Rate this book

208 pages, Paperback

Published May 1, 1985

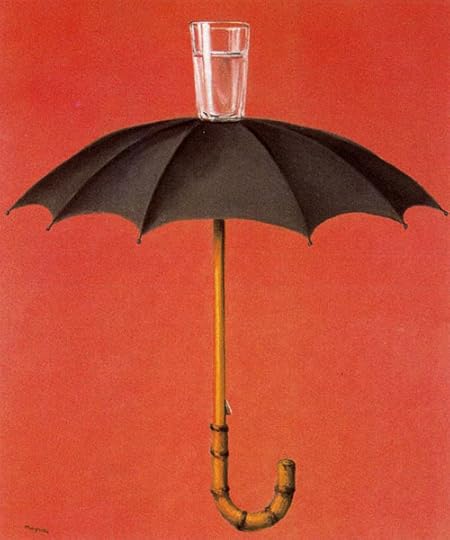

My latest painting began with the question: how to show a glass of water in a painting in such a way that it would not be indifferent? Or whimsical, or arbitrary, or weak — but, allow us to use the word, with genius? (Without false modesty.) I began by drawing many glasses of water, always with a linear mark on the glass. This line, after the 100th or 150th drawing, widened out and finally took the form of an umbrella. The umbrella was then put into the glass, and to conclude, underneath the glass. Which is the exact solution to the initial question: how to paint a glass of water with genius. I then thought that Hegel (another genius) would have been very sensitive to this object which has two opposing functions: at the same time not to admit any water (repelling it) and to admit it (containing it). He would have been delighted, I think, or amused (as on a vacation) and I call the painting Hegel's Holiday.

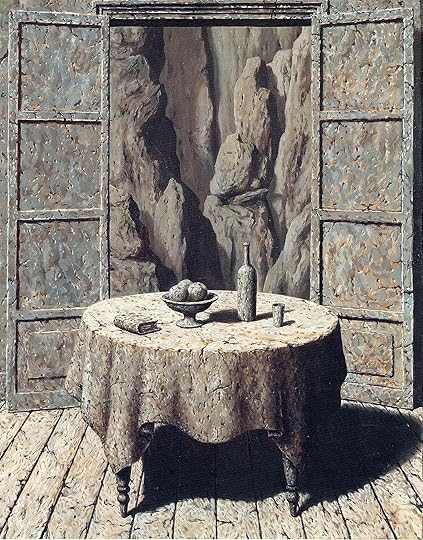

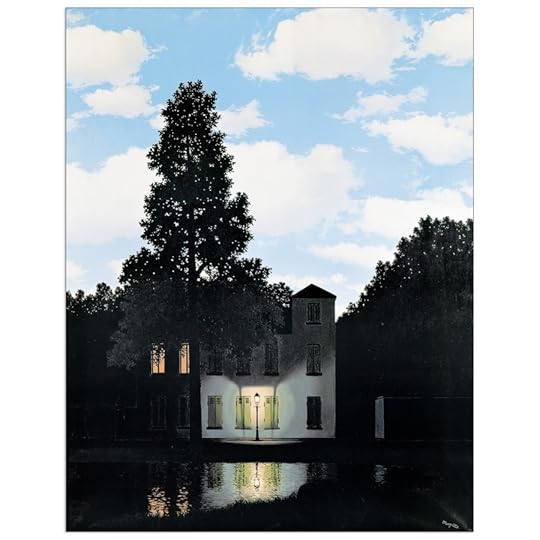

Just as with the ambiguity of 'inside' and 'outside', Magritte avoids any absolute finality of placement by playing on the bipolarity of 'here' and 'there'. As in The Empire of Lights, where he has used two apparently irreconcilable events (night and day) observed from a single point of view to disrupt our sense of time, in paintings like The Battle of the Argonne Magritte has similarly disrupted our sense of space.

What appears inevitably true in one sense, because it has been endorsed by reason, is an oversimplified and limited notion of the possibilities of experience, since it does not take into account the ambivalent, paradoxical nature of reality. In Magritte's paintings, everything is directed towards a specific crisis in consciousness, through which the limited evidence of the common-sense world can be transcended.