What do you think?

Rate this book

144 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1986

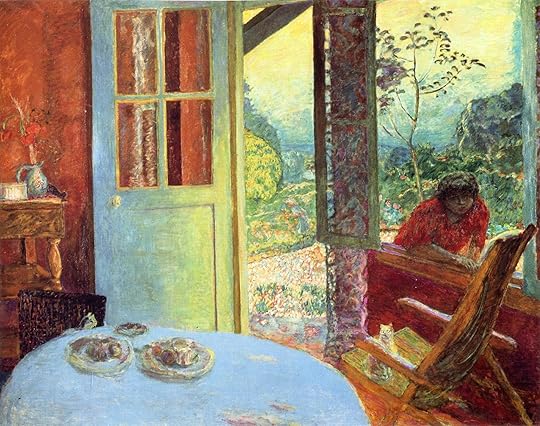

"I do not know what really went on between you. I do not know the first thing about you, either individually or together. Which is a strange thing for a child to confess to her parents."

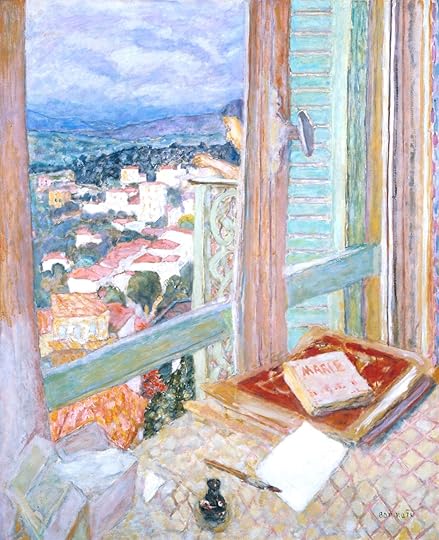

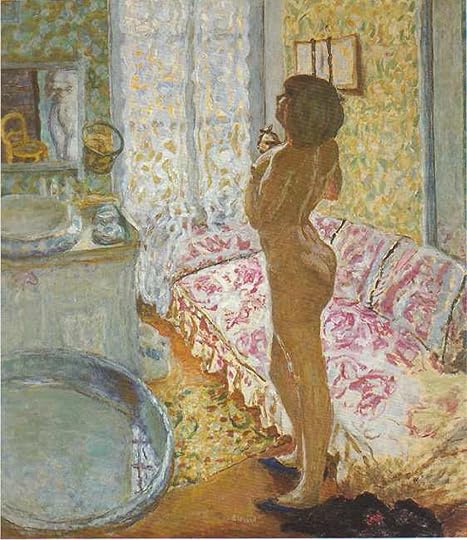

"I had been so proud of my skin. One of my best features, people said. It was because of my skin that your father wished to paint me in the first place. Your creamy skin, he said."

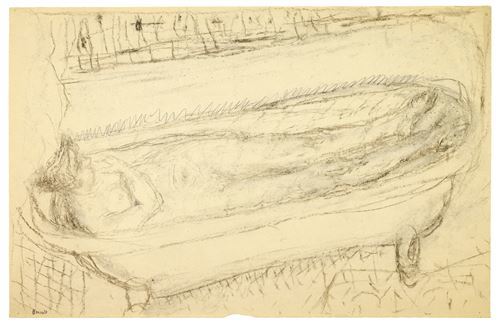

"It was the inability to cope with you that had brought it on. The only way to get rid of it was to send you away for a while...

"...I couldn't bear the itching...Only when I lay in the warm water did the pain cease for a while...a gentle sponging was the only thing that soothed it."

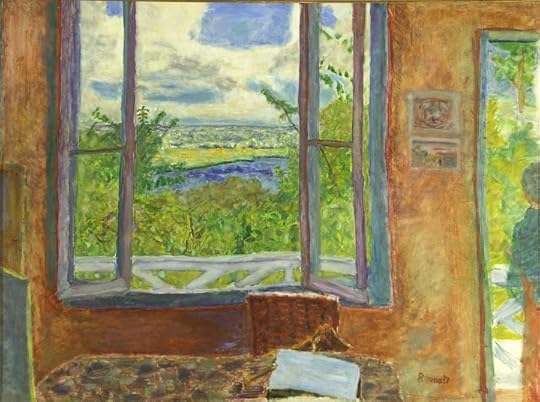

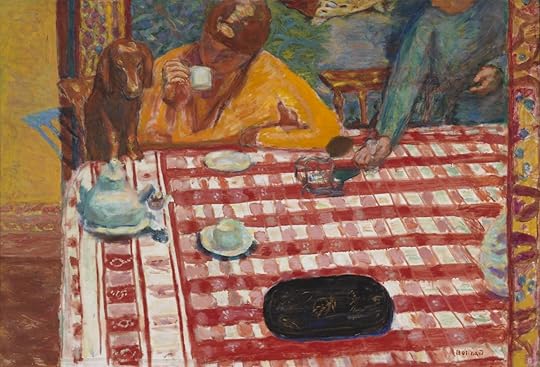

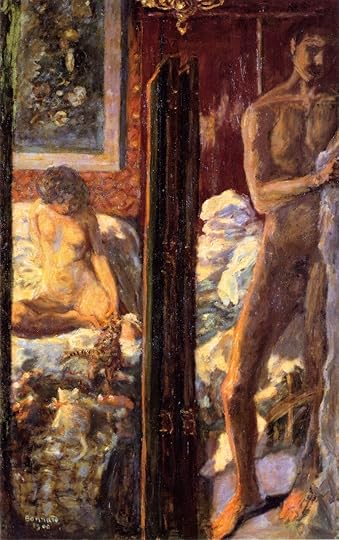

When I wrote a novel that took off from the relations of Bonnard to his wife, I didn’t want to write ‘a novel about Bonnard’, mainly out of respect for Bonnard — I wanted to be free to use what I wanted about that relationship and about Bonnard the painter, and to shed the rest. So I called it Contre-Jour, in homage to the painter, and subtitled it ‘A Triptych after Pierre Bonnard’ — which I hope gets it about right.

Contre Jour: A Triptych After Pierre Bonnard was a chance thing. I heard a talk on the radio about a Paris exhibition that featured many of his nudes in the bath. The speaker explained the one reason there were so many of them was that Bonnard’s wife was a compulsive washer. I dropped everything. I don’t know why. I went to Paris and had a look at that exhibition. I had dismissed Bonnard as being very beautiful like Renoir and a bit obvious, but I realised that he was not like that at all, but was very strange. The book came very quickly, almost as if I was copying it down and was not even writing it or inventing – it was all there.

John Berryman says in one of his poems, “Write as short as you can, in order, of what matters.” I like that.