If Kurt Vonnegut had written a political thriller it would have read a lot like this.

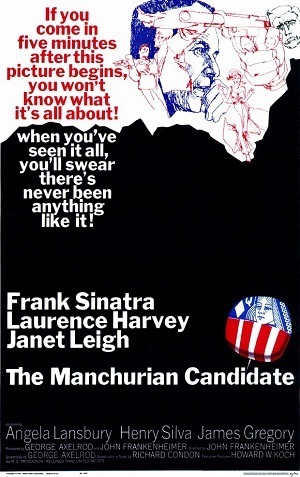

The Manchurian Candidate is famous now for two reasons. First, it has inspired two films, one directed by John Frankenheimer in 1962, the other by Jonathon Demme in 2004. Second, it has proven as gloomily prophetic a political satire as has George Orwell's also-classic 1984. Let's talk about that second point.

Consider this passage:

"Nonetheless her Johnny had become the only American in the country's history of political villains, studding folk song and story, to inspire concomitant fear and hatred in foreigners, resident in their native countries. He blew his nose in the Constitution, he thumbed his nose at the party system or any other version of governmental chain of command. He personally charted the zigs and zags of American foreign policy at a time when the American policy was a monstrously heavy weight upon world history. To the people of Iceland, Peru, France and Pitcairn Island the label of Iselinism stood for anything and everything that was dirty, backward, ignorant, repressive, offensive, antiprogressive, or rotten, and all of those adjectives must ultimately be seen as sincere tributes to any demagogue of any country on the planet."

The demagogue under review here is the oafish senator stepfather character, Johnny Iselin; however, his name could easily be replaced with "George Bush", Iselinism with "Bushism", and we have in our hands a harrowing fifty-years-in-advance prediction of American policy for the first eight years of the Twenty-First Century. Let me repeat: Harrowing.

The Manchurian Candidate's renewed popularity can be attributed to its cinematic connections and its prophesy. But the novel satisfies on many other levels, too. It is a time-capsule, a convincing glimpse at 1950s American war mentality and paranoia. It is a model of wryly disconnected prose, reminiscent of Vonnegut, wherein a careful reader can lose his- or herself in the allusions and puns and absurd descriptions. It is an insightful character study about a woman who lusts for power and about the depths to which she will reach to achieve political domination. It is a tender portrait of two war-ravished men whose friendship nearly redeems them. And it is an expertly twisted suspense yarn -- one of the best I have ever read.

It's become nearly impossible to discuss this particular book without reference to either of the movies, and I suppose that's a compliment to the movies themselves, the first of which is a bona-fide classic, the second of which is a better-than-average action flick. But maybe Manchurian would have made a better opera or miniseries than a movie; the novel is layered and more deeply developed than any two- or three-hour movie could ever be. In any case, whether you love the movie (how couldn't you?) or haven't ever seen it, you'd do yourself a favor to read the book. It's marvelous.