What do you think?

Rate this book

532 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 1863

"The Caucasus appeared quite different from what he had imagined it to be. Here he had found nothing that resembled his dreams, or the descriptions of the Caucasus he had heard and read. 'Here there are no burkas, rapids, Amalat-Beks, heroes or villains,' he thought. 'People live as nature lives: they die, are born, copulate, are born again, fight , drink, eat, rejoice and die again, and with no restrictions but those unalterable ones that nature has placed on the sun, the grass, the animal and the tree. They have no other laws but those . . . '"

"Where in this narrative is there any illustration of evil that is to be avoided? Where is there any illustration of good that is to be emulated? Who is the villain of the piece, and who its hero? All the characters are equally blameless and equally wicked.

Neither Kalugin with his gentleman's gallantry . . . and personal vanity -- the motive force of all his actions -- not Praskukin who, in spite of the fact that he falls in battle for 'Church, Tsar and Fatherland', is really nothing more than a shallow, harmless individual, not Mikhailov with his cowardice and blinkered view of life, nor Pest -- a child with no steadfast convictions or principles -- are capable of being either the villains or heroes of my story.

No, the hero of my story, whom I love with all my heart and soul, whom I have attempted to portray in all his beauty and who has always been, is now and will always be supremely magnificent, is truth."

The flush of morning has but just begun to tinge the sky above Sapun Mountain; the dark blue surface of the sea has already cast aside the shades of night and awaits the first ray to begin a play of merry gleams; cold and mist are wafted from the bay.So I turned to the more modern translation by David McDuff in the Penguin collection:

The light of daybreak is just beginning to tint the sky about the Sapun-gora. The dark surface of the sea has already thrown off the night's gloom and is waiting for the first ray of sunlight to begin its cheerful sparkling. From the bay comes a steady drift of cold and mist.Actually, reading on, I saw that both translations were more or less equally flowery, but in different ways. It is clear that, already the ironist, Tolstoy exploited the radiance of nature as contrast to the scenes of death and battle. So I stuck with the Penguin, which also has the advantage of notes, maps, a glossary, and an excellent introduction by Paul Foote. For now, I am confining myself to the Sevastopol Sketches; if I go back to read the Cossack Stories and Hadji Murat, also included here, I shall write a separate review.

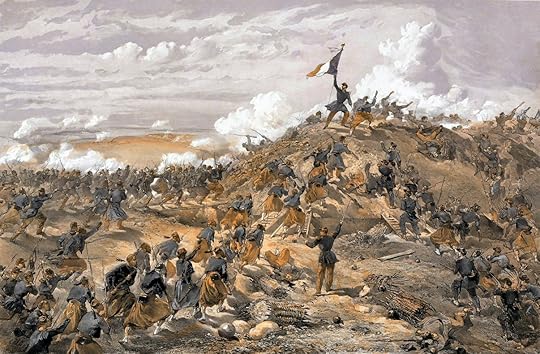

When they had talked all they wanted to, and had finally begun to feel the way close relatives often do—namely, that although each is very fond of the other, they neither of them have terribly much in common—the brothers fell silent for quite a long time.Subsequent chapters will shift between the two of them, gaining much from the contrast between the innocent and experienced views, and full of fascinating vignettes of their fellow soldiers—in the end showing that no man is immune to fear, but that there is a spark of heroism in all of us. The climax, seen interestingly through a telescope from a distant lookout, shows the capture of the vital Malakoff Hill by the French, which led to the Russian evacuation of the city the next day.

You will suddenly have a clear and vivid awareness that those men you have just seen are the very same heroes who in those difficult days did not allow their spirits to sink but rather felt them rise as they joyfully prepared to die, not for the town but for their native land. Long will Russia bear the imposing traces of this epic of Sevastopol, the hero of which was the Russian people. [December, 1854]

But the dispute which the diplomats have failed to settle is proving to be even less amenable to settlement by means of gunpowder and human blood. […] One of two things appears to be true: either war is madness, or, if men perpetrate this madness, they thereby demonstrate that they are far from being the rational creatures we for some reason commonly suppose them to be. [May, 1855]

Each man, on arriving at the other side of the bridge, took off his cap and crossed himself. But this feeling contained another—draining, agonizing, and infinitely more profound: a sense of something that was a blend of remorse, shame, and violent hatred. Nearly every man, as he looked across from the North Side at abandoned Sevastopol, sighed with a bitterness that could find no words, and shook his fist at the enemy forces. [August, 1855]======