What do you think?

Rate this book

320 pages, Hardcover

Published June 18, 2024

There’s a lot of evidence in this book to undermine the clichés of middle age. But one I cannot dispute is the sharpening sense of leaving. People we care about start to leave the world with more frequency. And then there’s the acute realization that we ourselves are going to disappear and no longer be part of the carefully constructed existence we’ve built with everyone and everything we love. And that if we get the privilege of more days, there will inevitably be that stripping away of abilities that make all of us us. We can do things that improve our chances of putting off this final leaving. But there are no guarantees, and as of right now, science has not yet discovered the elixir for immortality. And so our certain, ultimate exit remains a fact. In this sense, I find the story of humanity to be in equal measures the most beautiful and most cruel of narratives. We are born to experience the wonders of life, only to inevitably lose it all.

In the area of entrepreneurship, where the lore of the twentysomething start-up founder turned billionaire looms large, research from MIT’s Sloan School of Management found that for the highest-growth new ventures, the mean founder age was forty-five. “Our primary finding,” the MIT research team notes, “is that successful entrepreneurs are middle-aged, not young.” Martha Stewart was closing in on fifty before she signed a deal to launch her eponymous magazine, Martha Stewart Living. The founders of Geico and Home Depot were roughly the same age as Stewart when they launched those businesses. At sixty-two, Harland David Sanders franchised Kentucky Fried Chicken for the first time.

It’s when that momentum slows, when all the learning and box checking begins to feel no longer progressive but increasingly repetitious (rise, work, eat, family, bills, chores, bed; rinse and repeat) that we become most vulnerable. We sense it when we wake up and when we try to fall asleep. We’re unsettled, slightly bored but too busy to know it, and something is now off-key.

...

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle theorized about middle age as being the prime of life, a time associated with having reached full competence and mastery, with the body being fully developed sometime between thirty and thirty-five and the mind at forty-nine.

...

How to fix this feeling was slippery to get my arms around, though, because I’d chosen all of these things—the person I loved, the place we called home, the way I earned money. There were a lot of boxes checked, and I wasn’t interested in unchecking them. I recognize this isn’t true for everyone. For some, middle age may legitimately touch down like a tornado, wiping out what was there before and leaving no choice but to rebuild. This may be needed and even welcomed in some cases, or a terrible shock in others. But because I didn’t hate my existing life or want to blow it up in any obvious way, I wasn’t sure what to do. It was more like a long stretch of overcast days that sneak up and leave you with the dull ache of being inside for too long. You don’t hate your house, but you don’t want to stay in there all the time either.

...

When we ultimately spoke, Setiya told me he too had reached a point in adulthood where, somewhere between securing tenure and writing a second book, he felt a yawning void and was deeply confused about why. “I still liked philosophy. I liked teaching. I loved my students, and it all seemed worthwhile. And yet at the same time, it seemed futile and repetitive to just keep doing it over and over again, writing another paper and teaching another class. And I thought, There is a puzzle about why you would feel like something is deeply wrong with your life when you are doing things worth doing and very fortunate to be able to do them and basically things are going well.”

...

So, what is the solution? Weirdly, the answer seems to be something of a paradox: acceptance and action.

...

Enter the telic versus atelic framework. It’s not about action for action’s sake, Setiya believes, or cramming more to-dos into our already full lives. Rather, it’s about making room for activities or pastimes that bring lasting existential value to us versus focusing on only those whose value may wane once completed. This is the difference between an atelic and a telic activity—the words being derived from the Greek word “telos,” which means “end.” A telic activity, Setiya explained, is designed for immediate or finite gratification and has a definitive ending, like eating a good meal, writing a report, or taking a vacation. By comparison, an atelic activity is in service to something greater that delivers ongoing internal fulfillment, like listening to music or practicing your fly-fishing cast. You’ll never be totally finished, and that’s the beauty of it. In middle age, when you’re turning toward endings, such atelic activities can be far more fulfilling because they aren’t finite.

...

Now, thanks to Setiya, Austad, and Hutchinson, I could see very clearly why I’d been a sitting duck for the midlife assassin: FOMO, for starters. An incessant focus on finite telic activities and unsustainable—and ultimately unsatisfying—benchmarks for productivity. Disconnection and distance from family. Inertia. Sitting. Screens. Too much comfort. Too little discomfort. It all made what came next make a whole lot more sense.

Equally treacherous are the “time-suck slices,” as I come to think of them. These are the five-, ten-, and fifteen-minute expenditures of energy on little tasks that randomly occur to me throughout the day. Ordering new water pitcher filters on Amazon, replacing a lightbulb on our lamppost, making a dentist appointment, remembering we also need AA batteries and going back on Amazon. All the little adulthood necessities that seem like quick to-dos, particularly because many are now just a click away on my phone or computer. But they prevent me from finding concentrated blocks of time for anything important. Instead, I begin making lists and bucketing these activities for defined hours of specific days.

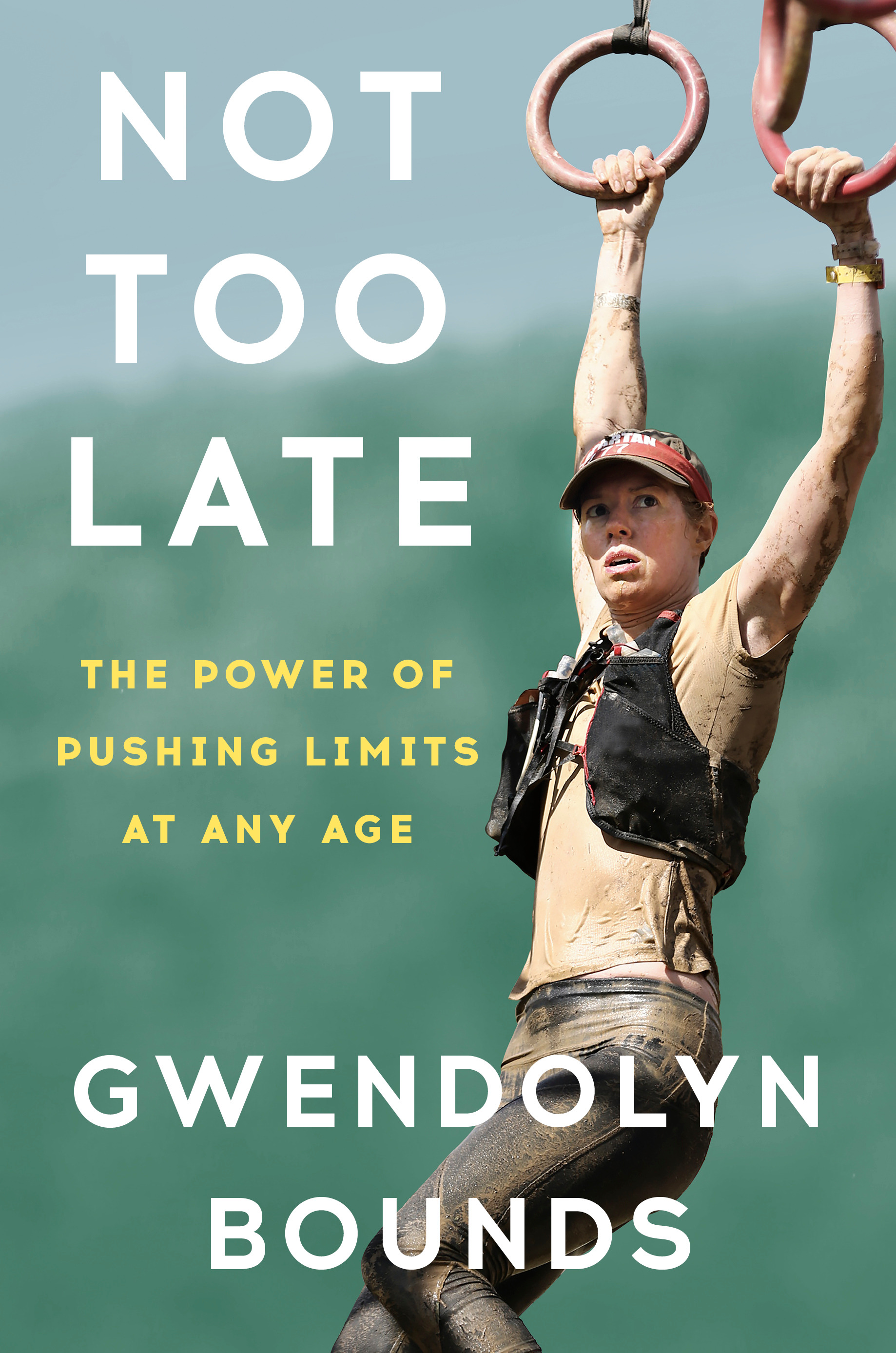

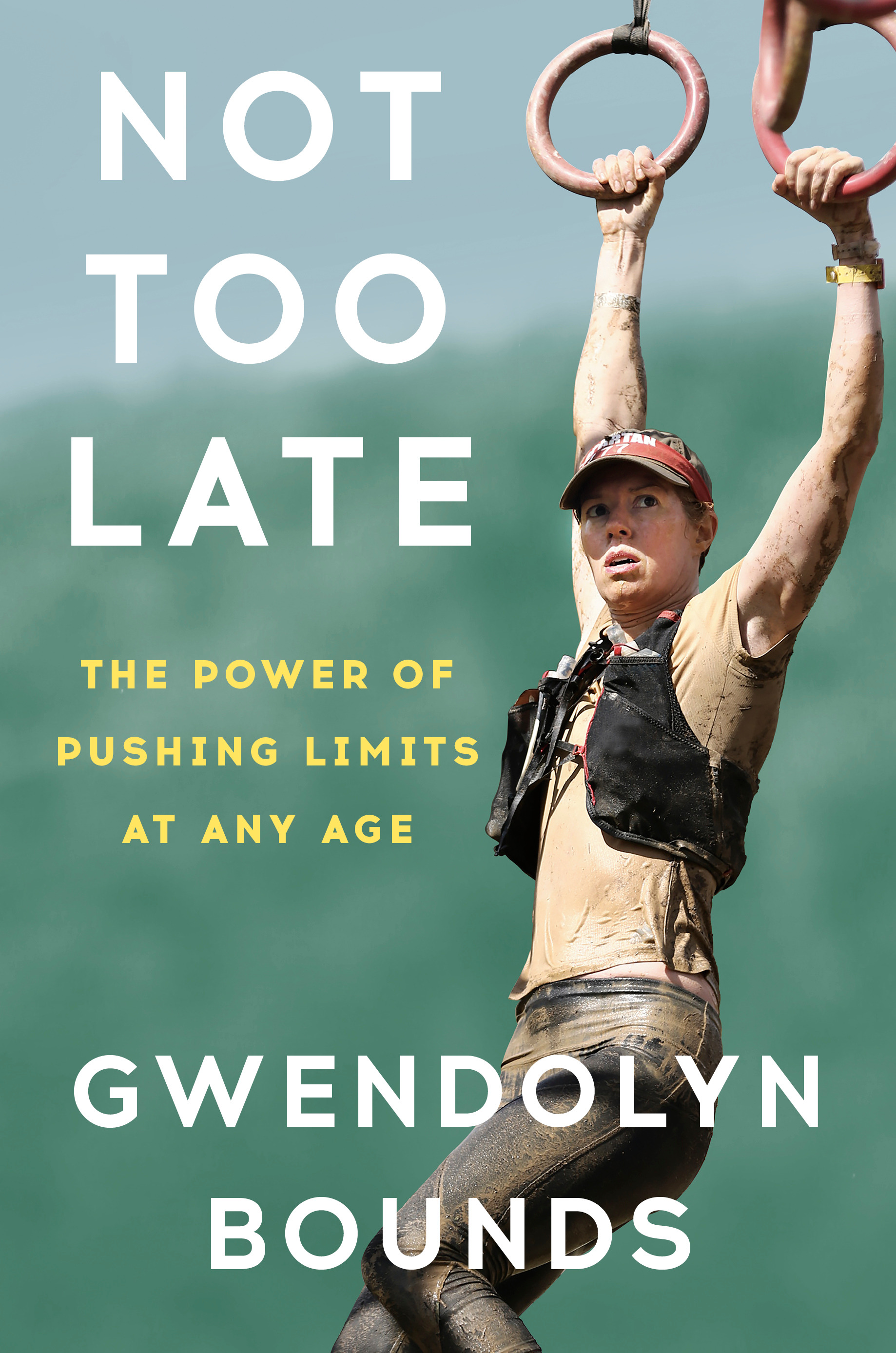

But as my former colleague Joanne Lipman, the author of Next!, put it to me, “Having an alternate identity is really protection for yourself.” And she is right. My identity as a competitive obstacle racer acts like a shield against the barrage of what-ifs that come with hard decisions.

...

As I get better at something hard and once seemingly out of reach, the sense of empowerment permeates the rest of my world. For the first time in my adult life, work is no longer the first and last thing on my mind when I awake and go to sleep. After I close my eyes at night, I replay different foot techniques of rope climbing in my mind instead of chewing on the annoying thing my colleague said in a meeting. I make my points to co-workers with increasing confidence, including that guy who always interrupts. (Dude, I can climb a seventeen-foot rope!) My decision-making sharpens; I answer emails when they land in my inbox and don’t punt until later. Maybe it’s a byproduct of making quick choices like where to place my foot on the rocks while running. Or maybe, with my training, I simply don’t have as much time to waste. My body is changing too. T-shirts once loose in my shoulders no longer fit comfortably. At night I sleep so hard, I barely wake up to use the bathroom. The baby calluses stop peeling off and become permanent grown-up calluses. I begin to track my resting heart rate at night with my watch and note that it has dropped to a low of around forty-nine beats per minute from the high fifties. My physical energy levels are the most robust I can remember since my early twenties. The long stints of sitting around conference tables during meetings at work make my body increasingly restless. I start standing behind my chair, trying to ignore the perplexed looks from our chief financial officer. Soon, I notice, our chief digital officer stands up too. And then our head of testing as well.