What do you think?

Rate this book

320 pages, Paperback

First published September 19, 2023

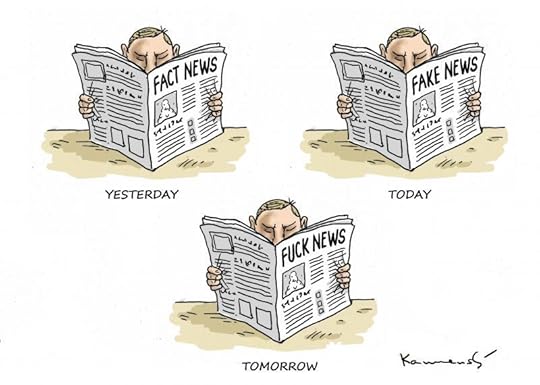

"...Technology, politics, economics, and more play a role in driving and accelerating these problems. With the advent of advanced AI tools such as ChatGPT and its siblings and the ongoing polarization of everything, it’s hard to see from a societal and structural perspective how we might solve them anytime soon. What fascinates me—and where I see leverage for positive change—is understanding why people are so susceptible. Why do we not only believe but actively seek and spread misinformation? What is the process by which a seemingly rational person begins to entertain, adopt, and then defend irrational beliefs? Approaching these questions with empathy, rather than judgment or ridicule, is both illuminating and disconcerting."

"...In this book, I will use the term misbelief to describe the phenomenon we’re exploring. Misbelief is a distorted lens through which people begin to view the world, reason about the world, and then describe the world to others. Misbelief is also a process—a kind of funnel that pulls people deeper and deeper. My goal in this book is to highlight how anyone, given the right circumstances, can find themselves pulled down the funnel of misbelief. Of course, it’s easiest to see this book as being about other people. But it’s also a book about each of us. It’s about the way we form beliefs, solidify them, defend them, and spread them. My hope is that rather than simply looking around and saying to ourselves, “How crazy are those other people?,” we will start to understand—and even empathize with—the emotional needs and psychological and social forces that lead all of us to believe what we end up believing.

Social science provides us with a valuable set of tools for understanding the various elements of this process and for interrupting or mitigating it. Much of the research I present in these pages is not new. I have found myself returning to some of the cornerstones of the field in my quest to shed light on the emotional, cognitive, personality, and social elements that lead people into misbelief. This isn’t surprising. After all, a propensity for misbelief is part of human nature..."

"My friends warned me not to see you because they said you put a spell on me."

“How can you prove that your sister is not a prostitute when you don’t even have a sister?”

Hanlon’s razor. The original Hanlon’s razor states, “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

Occam’s razor. The basic idea of Occam’s razor is that the simplest explanation with the fewest moving parts is the one we should favor, until it is proven inadequate. Just to be clear, Occam’s razor does not say that the simplest explanation is always the right one, only that when we don’t have any data to help us pick one explanation over another, we should pick the simplest one.

The principle of the pain of paying, which posits that it hurts to part with cash but it hurts less when we don’t see or pay attention, helps us understand why we overspend when we use credit cards; why we feel worse at the end of a meal when we pay with cash compared with a credit card; why we sometimes prefer all-inclusive vacations even if they are more expensive; why we often go over budget when we renovate our homes; and much more.

Proportionality bias is the idea that when we are faced with a large event, we implicitly assume that such an event must have been caused by proportionally large causes. The reality of life is that often “shit happens” without any rhyme or reason. Randomness and luck (including bad luck) are important forces in the universe, as is human stupidity, but this is an unnatural way for us to think. We look for reasons, for causes, and when something is larger, we look for larger causes. Interestingly, the proportionality bias does not seem to apply to positive events. When amazing inventions are developed, such as penicillin, Post-it Notes, X-rays, Teflon, Viagra, and many others, we’re very comfortable attributing them to chance. In other words, when it comes to major good things, compared with major bad things, we are much likelier to believe that “shit happens.”

The third psychological reason favoring complexity is the desire for unique knowledge.

Together, all of these forces pull the misbelievers away from Occam’s razor and closer to Macco’s razor (the complete opposite of Occam’s razor), which states that “The most complex solution that involves the most devious intentions and the most hidden elements is almost always the truth.”

Hitchens’ razor, named after Christopher Hitchens, the late literary critic, journalist, contrarian, and staunch atheist: “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”

"Mistrust begets mistrust...

...mistrusting... government, the medical profession, nonprofits, the media, and the elites."

The author does an interesting job of putting together a model for how people descend into an embrace of absurd misinformation, going through the emotional, cognitive, personality and social quirks of our thinking that add up to a funnel of misbelief for some people. It may not all be right, but it’s a valiant and thought-provoking attempt to understand this weird and disturbingly pervasive phenomenon of this age.