What do you think?

Rate this book

160 pages, Kindle Edition

First published June 24, 2021

GOAL! Borussia Dortmund 4-0 Schalke (Guerreiro 63)

This is a delicious goal. Guerreiro powers in diagonally from the left. He slips a pass inside for Haaland, just to the right of the D. Haaland returns it down the channel, Guerreiro having continued his diagonal run. Guerreiro then flicks home sensationally, flicking it with the outside of his boot into the right-hand side of the net.

“I’m Sterling. Lost my father to AIDS, my mother to alcoholism. Lost my country to conservatism, my language to PTSD. Got this England, though. Got this body, this Sterling heart.”It is 2001, and bullfights, as Sterling shows us, abound in Camden Town – as in the staged, ritualised slaughter of an animal undangerous until driven by provocation; as in the ceremonial harassment done against lone members of minority communities; AS IN the state violence committed against queer, immigrant, BIPOC, non-conforming people. In 2001 in Camden Town, Waidner deploys surrealism (spaceships, football, fashion, Google Earth-powered time travel, Patreon-funded sketch theatres, shapeshifting bestiaries, the 1967 Beach Boys album Smiley Smile and so on) to dive deeper into all that is otherwise triggering and harrowing about their subject matter, and have their characters and their friends hold the powers that be to account.

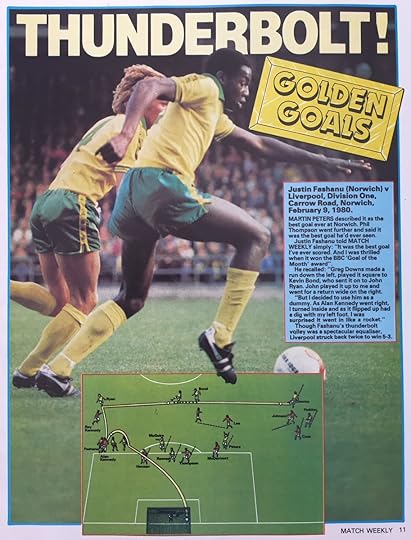

Waidner frames the dreamlike logic of this novel through Hieronymus Bosch’s fifteenth-century triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (the plaintiffs in the absurd trial against Sterling are named Hiero Moussi and Nimo Bosch respectively) and is as ripe with symbolism as the painting. Bringing together settings, characters, and incidents from observable history (notably the suicide of the black gay footballer Justin Fashanu) with exquisite, associative wordplay (“Picador is one of a pair of horsemen in a traditional bullfight who jabs the bull with a lance, and also a British publishing house”), it seeks to create narrative moments that reveal “incongruities and irregularities in the official narrative, so-called 'spaceship moments', to confirm what we already know, namely that we're alive in a sub-standard fiction that doesn't add up…that we [are] non-consensual participants in a reality put together by politicians, despots, more or less openly authoritarian leaders."![]()

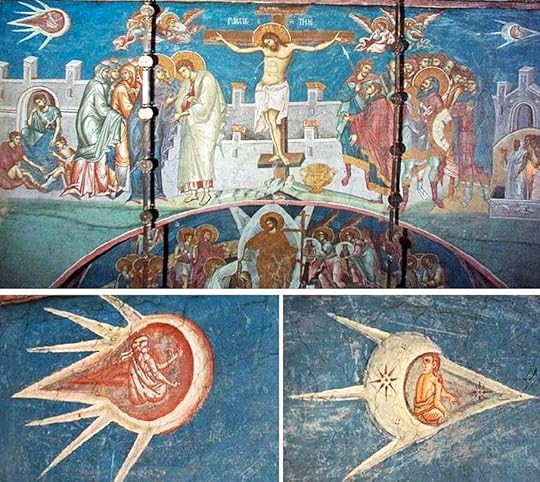

All in all, Sterling Karat Gold is Waidner’s exercise in imagining otherwise: in the words of Sterling’s ‘bestie’ and creative collaborator Chachki Smok, "Correcting falsified narratives is important, but conjuring counter-realities even more so." There are two moments, at nearly two opposite ends of the book, that when juxtaposed bring this idea to the forefront: during Sterling’s absurd trial, Chachki is called to testify and ask if their friend ‘at least partly exists in a dreamland of their own making.’ As the novel reaches full circle with its echoing of the opening scene of bullfighting as ritual violence, Sterling – no longer the victim – dares to ask: “What’s it like to exist on someone else’s terms? In someone else’s violent fiction?”A thirteenth century fresco from the Visoki Decani monastery in Kosovo (referenced in the book) depicts sun and moon figures that look vaguely like spaceships, leading many to believe that our ancestors made contact with aliens. Waidner, despite the spaceships in their novel, seems to imply that such assumptions downplay the richness of human creativity and imaginativeness that predates modernity and is likely to outlive it.

Take Cataclysmic Foibles, the name, which referred to a state of precarity in which any foible, character flaw, or momentary slip up can and will have cataclysmic personal consequences, imagine, e.g., that all you did was walk down Delancey Street, white football shirt wrapped round your waist like a skirt… That’s what years ago we somewhat childishly, imprecisely - liberally, even - called a cataclysmic foible, the fact that you wore that stuff, the skirt in particular, the fact that it was never actually about your clothes but always about you, and that if you hadn’t worn this or that skirt, or those socks, you would’ve had the exact same thing coming, the kind of thing, Justin Fashanu, that doesn’t happen to everybody, but that happened to us, Justin, and to you, a lot, that’s why we developed a language around it, we were kids, didn’t care for the precise or even correct use of words, we still don’t, we care for their capacity to give life, and to take it away.

"Instead, he strains his neck. Is this the moment he realises what he has let himself in for? What it means for him to give up control, even if temporarily and in the context of an artistic performance? What it's like to exist on someone else's terms? In someone else's vio lent fiction?"