What do you think?

Rate this book

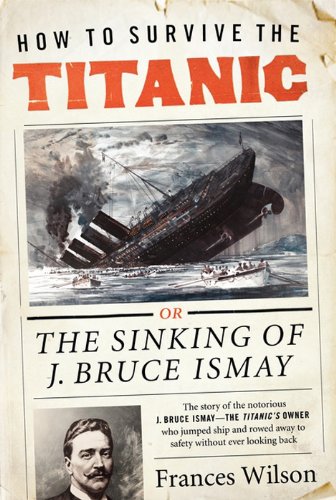

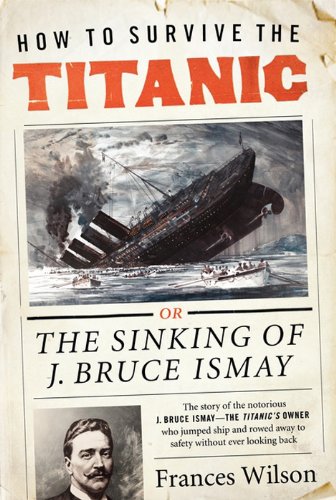

A brilliantly original and gripping new look at the sinking of the Titanic through the prism of the life and lost honor of J. Bruce Ismay, the ship’s owner

Books have been written and films have been made, we have raised the Titanic and watched her go down again on numerous occasions, but out of the wreckage Frances Wilson spins a new epic: when the ship hit the iceberg on April 14, 1912, and one thousand men, lighting their last cigarettes, prepared to die, J. Bruce Ismay, the ship’s owner and inheritor of the White Star fortune, jumped into a lifeboat filled with women and children and rowed away to safety.

Accused of cowardice and of dictating the Titanic’s excessive speed, Ismay became, according to one headline, “The Most Talked-of Man in the World.” The first victim of a press hate campaign, he never recovered from the damage to his reputation, and while the other survivors pieced together their accounts of the night, Ismay never spoke of his beloved ship again.

In the Titanic’s mail room was a manuscript by that great narrator of the sea, Joseph Conrad, the story of a man who impulsively betrays a code of honor and lives on under the strain of intolerable guilt. But it was Conrad’s great novel Lord Jim, in which a sailor abandons a sinking ship, leaving behind hundreds of passengers in his charge, that uncannily predicted Ismay’s fate. Conrad, the only major novelist to write about the Titanic, knew more than anyone what ships do to men, and it is with the help of his wisdom that Wilson unravels the reasons behind Ismay’s jump and the afterlives of his actions.

Using never-before-seen letters written by Ismay to the beautiful Marion Thayer, a first-class passenger with whom he had fallen in love during the voyage, Frances Wilson explores Ismay’s desperate need to tell his story, to make sense of the horror of it all, and to find a way of living with the consciousness of lost honor. For those who survived the Titanic, the world was never the same. But as Wilson superbly demonstrates, we all have our own Titanics, and we all need to find ways of surviving them.

387 pages, Kindle Edition

First published August 1, 2011

Marlow would stretch out his legs after dinner on the deck of some barque, light his cigar, fill his glass, and tell Ismay’s tale to an audience of men who also follow the sea. First he would paint on his dark background the details so essential to the myth of the Titanic: there would be a ship the size of a cathedral, her monstrous birth in the Belfast shipyard; the decision to limit her lifeboats so as not to clutter the decks; her doomed beauty; the cheering, the pride, the jubilation as she slides down her cradle to taste the first drop of water; the ice warnings; the Captain driving her on and on, the moonless sky, the sudden appearance of the berg…the order to turn ‘hard-a-starboard’; the opening up of the ship like a tin of sardines; the torrential rush of water; the sleeping passengers; the dutiful crew; the Captain losing control; the band playing ragtime…the steerage passengers trapped down below; the half-filled boats dropping into the water; the men in their dinner jackets going down like gentlemen…the wives who chose to die with their husbands; the other wives in the lifeboats refusing to save their husbands…Marlow would linger over the many different languages spoken in the steerage compartments, the four Chinese sailors of Collapsible C, and he would save for his finest canvas the splendor of the Titanic’s final dive and the death-music that followed. But at the heart of his story would be Ismay’s jump and his subsequent battle with his moral identity, because for Marlow ‘the ship we serve is the moral symbol of our life’ and nothing can be said with certainty about a man until he has been ‘tested’ by his ship.