What do you think?

Rate this book

504 pages, Paperback

First published September 13, 2022

To Roland, from this threshold everything looked randomly imposed as though he had been lowered from a forgotten place into these circumstances, into a life vacated by someone else, nothing chosen by himself. The house he never wanted to buy and couldn’t afford. The child in his arms he never expected or needed to love. The random traffic moving too slowly past the gate that was now his and that he would never repair.

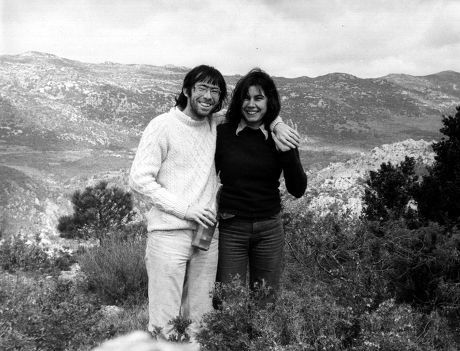

She crossed the room and went into the kitchen. Watching her bare white feet, hearing their scuffing sound on the flagstones, made him feel weak. A couple of minutes later she came back with glasses of orange juice, actual crushed oranges, a novel taste. By then, he was standing uncertainly by the low table, wondering if now he was expected to leave. He would not have minded. They drank in silence. Then she put her glass down and did something that almost caused him to faint. He had to steady himself against the arm of a sofa. She went to the front door, knelt and sank the heavy door bolt into the stone floor. Then she came back and took his hand.

“Come on then.”

“All right. She too deceived herself in marriage. She thought you were a brilliant bohemian. Your piano playing seduced her. She thought you were a free spirit. Just the way I thought Heinrich was a hero of the resistance and would go on being one. You misled her. ‘He’s a fantasist, Mutti, he can’t settle to anything. He’s got problems in his past he won’t even think about. He can’t achieve anything. And nor can I. Together we were sinking. Then there was the baby and we sank faster. Neither of us were ever going to achieve anything.’”

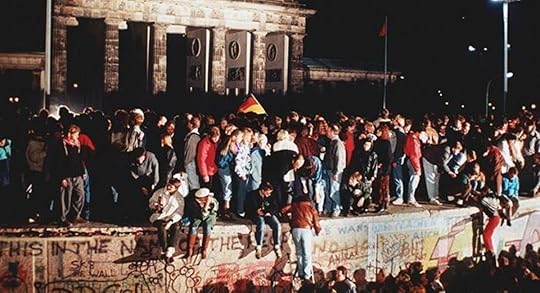

Among his subjects were other single starting errors that multiplied through time into a fan-shaped array. On close examination the errors dissolved into questions, hypotheticals, even into solid gains. On this last he may have been deluding himself. But in surveying a life it was inadvisable to acknowledge too much defeat. Marrying Alissa? Without Lawrence there would have been no joy, no Stefanie, Roland’s new best friend. If Alissa had stayed? He had reread The Journey in February and early March when he and most of the people he knew locked themselves down three weeks ahead of the government. Her novel remained exquisite. Leaving school early? If he had stayed, Miriam, by her own admission, would have hauled him from the classroom and he would have been sunk. Even now that thought, as if in prospect, stirred him just a little. Abandoning classical piano and the chance of becoming a concert pianist? Then he would never have discovered jazz, would never have run free in his twenties or learned to respect manual labour or developed a snappy backhand. He would have been bound to five hours a day practice for the rest of his life. ..... Should he have stayed in the Labour Party to argue for its liberal and centrist traditions? He would have been driven miserable and mad after four consecutive defeats. So his life was an unbroken succession of correct decisions? Clearly not. Finally he came to the true turning point, the moment from which all else fanned out and upwards with the extravagance of a peacock’s tail: the boy mounting his bike, mid-Cuban Missile Crisis, to present himself to Miriam for a two-year erotic and sentimental education with its ludicrous finale, the pyjama week, that terminated his schooling and distorted his relations with women. This was difficult. When he asked himself if he wished none of it had happened he did not have a ready answer. That was the nature of the harm.

He knew it could be pleasurable, handing out wise counsel. Receiving it could be suffocating when you’ve moved on. Where exactly? Backwards, twenty-seven years, to the core. Alissa’s vanishing had left open ground to the past. Like trees felled to clear the view. In rare moments like this, he could see the origin, a point of light in sharp focus, of all that troubled him and those who came close to him. The piano teacher haunting him that first night was often on his mind.

‘Do you think the story is trying to tell us something about people?’ She looked at him blankly. ‘Don’t be silly, Opa. It’s about cats and dogs.’ He saw her point. A shame to ruin a good tale by turning it into a lesson.

Novels and stories offer deceptive consolation about order and form. Someone is supposedly holding all the threads of the action, knowing the order and the outcome, which scene comes after which. A truly brave book, a brave and inconsolable book, would be one in which all stories, the happened and the unhappened, float around us in the primordial chaos, shouting and whispering, begging and sniggering, meeting and passing one another by in the darkness.

"It often happened like this, Roland thought, the world was wobbling badly on its axis, ruled in too many places by shameless ignorant men, while freedom of expression was in retreat and digital public spaces resounded with the shouts of delirious masses. Truth had no consensus."

"In your mid-thirties you could begin to ask what kind of person you were. The first long run of turbulent young adulthood was over. So too was excusing yourself by reference to your background. Insufficient parents? A lack of love? Too much of it? Enough, no more excuses. You had friends of a dozen years or more. You could see your reflection in their eyes. You could or should have been in and out of love. You would have spent useful time alone. You had a measure of public life and your relation to it. Your responsibilities would be pressing in, helping to define you. Parenthood must cast some light."

"But there was that essence everyone forgets when a love recedes into the past—how it was, how it felt and tasted to be together through seconds, minutes and days, before everything that was taken for granted was discarded then overwritten by the tale of how it all ended, and then by the shaming inadequacies of memory."

"He had reached that point—late thirties was common—when one’s parents set off on their downhill journey. Up until that time they had owned whoever they were, whatever they did. Now, little bits of their lives were beginning to fall away or fly off suddenly like the shattered wing mirror from the Major’s car."In his own old age, he can't believe how fast time is moving, and it is a cause of sadness for him and his peers:

"Two years sat lightly in memory, like two months. Time’s gathering compression was a commonplace among his old friends. They routinely shared their impressions of an unfair acceleration."