What do you think?

Rate this book

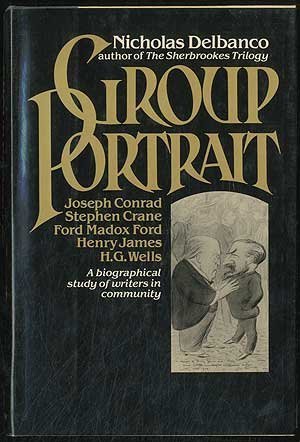

224 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1982

The Gulf Stream runs sufficiently near to allow this region escape from the forbidding chill that grips the north of England. Fig trees grow, and mimosa, and the occasional palm. It is a fertile landscape and well-farmed; apple orchards and fields of hop abound. Vegetables grow in Romney Marsh; the hillsides are close-cropped by sheep. The pastures are ample for cows. Potatoes can be harvested in August. Oasthouses rise from every farm, and larger farms have several, their conical brick shapes topped by a white wooden cap. White weatherboard is characteristic of Kent; the villages are gaily variegated. A Georgian brick house will abut an Elizabethan half-timbered pub; behind them rises the stone vaulting of a medieval church. It is a democratic muddle, a gallimaufry, a place where foreigners have felt at home since Hastings.At the end of the Victorian age and the dawning of the 20th century came the literal and figurative foreigners-conquerers Delbanco studies: the American adventurer Crane and expatriate James, the self-exiled Polish mariner Conrad, the Pre-Raphaelite scion Ford (then still going by his given name, Hueffer), and the upwardly mobile shopkeeper's-son-turned-prophet Wells. They came to work, and, fortified by Continental standards, to transform the English novel from mere entertainment or instruction to high art.

According to Cora's notebook, when she suggested that he write for pure plain cash, "He turned on me & said: 'I will write for one man & banging his fist on writing table & that man shall be myself etc. etc.'"Skilled not only in quotation but also in summation, Delbanco captions Crane's legend:

The recklessness so characteristic of Crane—the devil-may-care bravery that is the stuff of anecdote—seems an elected stance. It is the attitude of one who nerves and schools himself to manhood, as if war (and, at its farthest limit, suicide) were an initiation rite.The next chapter narrates the unusual collaboration between Conrad and Ford. The younger Ford was sometimes Conrad's idea man, sometimes his amanuensis, sometimes his ghostwriter. The elder writer struggled with his third and adopted language, and he struggled as well with his self-imposed Flaubertian standards. At times debilitated by gout and depression, he needed his more facile young friend to verbally solicit his dictated memoirs and even to fill in for a serialized chapter of his masterpiece, Nostromo. Ford in turn became more the self-conscious artist, less the rambling amateur, under Conrad's exacting influence. Delbanco, promoting collaboration to the fractious artistic temperament, summarizes:

If Poe preceded him, Hemingway succeeded him. The latter's motto of "grace under pressure" applies in retrospect.

And I submit that Ford released the elder man to create profound scenarios by helping him to realize the surface of his texts. [...] That Ford profited from the collaboration is beyond question; he says so himself and at length. A dilettante to start with, he became professional; the young and mannered dabbler grew to be "an old man mad about writing."The fourth chapter is probably the most interesting to the general reader. It dramatizes the famous argument over the nature and purpose of fiction between Henry James and H. G. Wells. James championed the aesthetic position, what would become the watchword of modernism: a novel should be a rigorously designed and finished work of art, as deliberate and complete as a painting, made as much by excluding inapposite subject matter as by patterning its essential contents. Wells, on the other hand, saw the novel as a subset of journalism and as a tool of social thought and political advocacy. For Wells, James's work was tediously ponderous and socially quiescent; for James, Wells's work was indiscriminate, unrealized, and vulgar. In this chapter, Delbanco mostly lets his principals have their dialogue as their friendship dissolves (they had once thought of collaborating) under the pressure of their ideological tussle.

No matter how uncertain in his early period, Wells's art was didactic—and, later, explicitly so. The assumption of the didact (particularly, perhaps, if he has been, as was Wells, an autodidact and a success story) is meliorist: things can get better and do. Conrad put it succinctly. He told Wells, "The difference between us is fundamental. You don't care for humanity but think they are to be improved. I love humanity but know they are not."In conclusion, we might ask: why is the Kentish convocation of the turn-of-the-century's major Anglophone writers less heralded than later modernist enclaves? Delbanco allows for one that this was a male preserve; as I've already discussed here, the period from roughly 1880-1910 in English letters was highly and willfully masculinist, more so than the periods that preceded and succeeded it. Kent and East Sussex did not have the presiding female geniuses of Bloomsbury or expat Paris—no Woolfs or Steins, only the wives and domestic servants that made the men's writing possible (though Woolf and Stein, it should be said, relied on similar support).