What do you think?

Rate this book

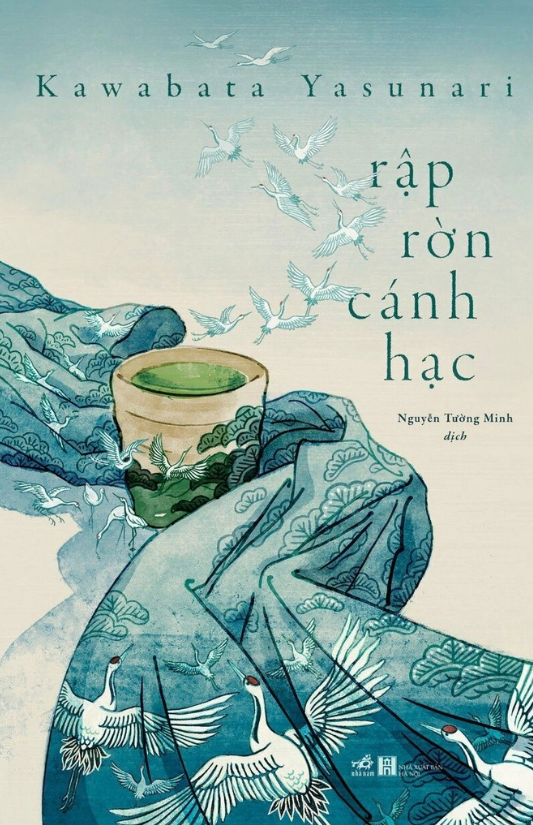

198 pages, Paperback

First published February 10, 1952

The memory of that birthmark on Chikako’s breast was concrete as a toad.

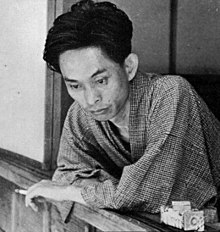

Here we have the emptiness, the nothingness, of the Orient. My own works have been described as works of emptiness, but it is not to be taken for the nihilism of the West. The spiritual foundation would seem to be quite different.

I may say in passing, that to see my novel Thousand Cranes as an evocation of the formal and spiritual beauty of the tea ceremony is a misreading. It is a negative work, and expression of doubt about and warning against the vulgarity into which the tea ceremony has fallen.

When you see the bowl, you forget the defects of the old owner. Father’s life was only a very small part of the life of a tea bowl.

Though it was broad daylight, rats were scurrying about in the hollow ceiling. A peach tree was in bloom near the veranda.

[image: InsideKyoto.com]

“When tea becomes ritual, it takes its place at the heart of our ability to see greatness in small things. Where is beauty to be found? In great things that, like everything else, are doomed to die, or in small things that aspire to nothing, yet know how to set a jewel of infinity in a single moment.”– Muriel Barbery