As someone who once wrote “I have never found anything any artist has said about his work interesting,” Janet Malcolm, in her latest (posthumously published) book “Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory”, accordingly says little about her work but a great deal about her life. Seen through the unforgiving lens of the camera and the unreliable eye of memory, veracity is, as she herself admits, arbitrary.

That Malcolm, so incisive a portraitist in words, should turn again to the camera as a conceptual device isn’t surprising. Photography as an art form has long beguiled her. As a staff writer for The New Yorker, she wrote for many years on art and interior design. Her first book, published in 1980 was “Diana & Nikon: Essays on the Aesthetic of Photography” A subsequent book “Forty One False Starts” included essays on photography and photographers. In writing about Thomas Struth, she says “photography is a medium of inescapable truthfulness. The camera doesn’t know how to lie.”

Inescapable truthfulness is, of course, a trademark of the Malcolm style. As for the camera, it may not lie but it can conceal – move the frame slightly, change the angle, adjust the focus and what you see may be either less or more than the truth. Likewise, in her memoir, Malcolm’s disclosures may not be more than the truth, but they are redacted. We are given fragments of the life seen from angles.

For a writer who had a reputation as “a formidable interviewer and a ferocious portraitist” Malcolm was very diffident when it came to writing about herself. “I would rather flunk a writing test,” she said, "than expose the pathetic secrets of my heart.”

Writing of an abandoned attempt at autobiography in 2010 in The New York Review of Books she said the journalist who tries to write an autobiography "has more of an uphill fight than other practitioners of the genre". The unsparing, rational "I" of journalism must be discarded in favour of the softer, more indulgent "I" of autobiography, one who tells their story "as a mother might ... with tenderness and pity, empathising with its sorrows and allowing for its sins." Judging herself a failure at this she says, "Not only have I failed to make my young self as interesting as the strangers I have written about, but I have withheld my affection”.

There is no such failure here, either of interest or affection. Wry admissions of youthful callousness notwithstanding, there’s a softness in the “I” of this memoir. Of the photos, many of which she found in a box in her apartment, she is less forgiving, at least at first glance, judging them gray and uninteresting and comparing them to “barely flickering dreams that dissipate as we awaken”. But, on closer examination, “the drab little photographs” begin to speak to her.

They speak of people and relationships and the unfolding of a young child's formative years within the immediate circle of family and the larger crucible of tumultuous world events. Like the collages she enjoyed creating in later life, these assembled photographs are ephemeral in nature, small sketches that suggest a greater theme.

In the observations provoked by the photographs, it’s the woman rather than the writer who steps from the frame. Despite her reputation as a formidable journalist, her take no prisoners approach to interview subjects and her skewering of fakery in all its forms, the self-portrait we see here is relatable and engaging. Humour, a droll self-deprecation, warmth and a kinder acceptance of the frailties of herself and others round off the sharp edges of the public portrait.

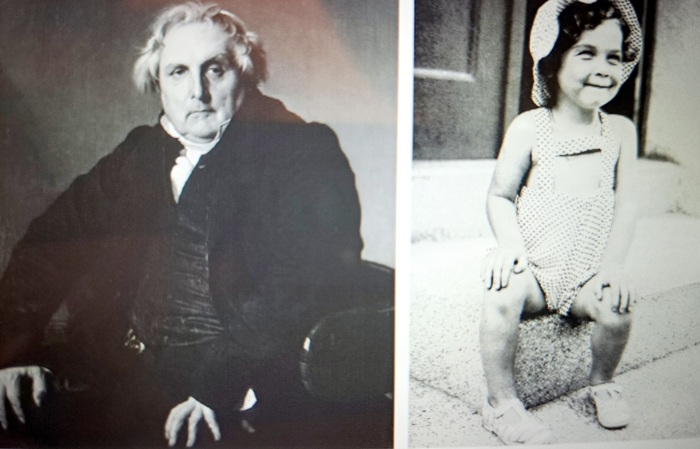

We’re first introduced to the author as a toddler, aged two or three, sitting on a doorstep, dressed in a sunsuit and hat, hands on knees, grinning, as if at something funny someone’s said to her. To the adult Malcolm, this child is unrecognisable. A few years later we see a young girl aged nearly five looking out with her parents from the window of a train taking them from Prague to Hamburg. Again, Malcolm has no memory of being that girl. Or of knowing they were to board a ship taking them to a new life in New York. It’s only in hindsight she learns the momentous nature of the journey, that they were fleeing Czechoslovakia to escape the Nazis because they were Jewish. Like a curtain unfurling, the unrecognisable slowly appears, takes on meaning and allows the interpretation of what meant little to the child at the time - her family’s national and racial identity, their assimilation into a new country and how she and her sister’s imaginative lives were inexorably shaped by those experiences.

This collection was composed of various pieces she wrote at different times, never intending them to form a memoir or autobiography, but rather seeing them as improvisations, explorations of the close interrelationship between the visual and the written. Fragmentary though this approach might suggest, it coheres as memoir, notwithstanding her statement that ”memory speaks only some of its lines”. With characteristic elegance, she rationalises the incompleteness of the final result – “most of what happens to us goes unremembered. The events of our lives are like photographic negatives. The few that make it into the developing solution and become photographs are what we call our memories.”

Incomplete they may be, but these glimpses into the life and career of a legendary writer will become as deservedly acclaimed as her other works. Like photography itself, the significance lies in what’s revealed. As Ian Frazier (a close friend) says in his introduction to the book “she wrote these pieces at a level of wisdom that took a lifetime to attain, and that almost nobody reaches at any age.”

Janet Malcolm’s book was of special interest to me, as in an extraordinary reversal of circumstances, I once interviewed her. This happened a few years ago in New York at an unmemorable restaurant on Broadway on a wintry Sunday afternoon. To say it was an occasion that immediately went into the developing solution of my memory is a huge understatement, as I’ll never forget it. Well may you ask what I, a modest uncelebrated scribbler from little old Adelaide, was doing in New York but more to the point, sitting across a table from one of the literary lions of our age.

Here's how it happened.

In the embryonic stages of the book I was trying to write, I’d somehow convinced a government arts funding body it would be a worthy act to finance me on a research trip to the US and Paris. My powers of persuasion proved greater than my powers of getting the book published as it’s turned out, but we won’t go there. Janet Malcolm’s remarkable book “Two Lives: Alice and Gertrude”, had become a cornerstone of my reading on Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, the putative subjects of my putative book. Janet Malcolm, I knew, lived in New York and so it was but a small step to email her and request an interview. (One of the dubious benefits of email is it makes it all too easy to practice the nothing ventured nothing gained approach).

That she not only replied but agreed to give up her time to an unknown, unpublished and unproven Australian writer seemed to me evidence that miracles happen. More to the point, it was evidence of her remarkable generosity, openness and graciousness.

Lacking photographs, here are the assembled fragments of memory:

I arrived late in a sweating, red faced panic after the cab somehow got lost between my hotel and the restaurant. She waited.

In a fluster of fumbling for my notebook, I dropped everything out of my handbag onto the floor. She pretended it didn’t happen.

I said it was hard to hear above the music. She asked a waitress to turn it off.

I said it was hard to write about legends like Stein and Toklas. She asked ,with a cheeky smile, if I was going to mention Toklas’s moustache.

I apologised for sniffing (I had a cold). She said she had one too.

On parting, I started babbling about how grateful, how appreciative, how lovely … etc. etc. She said when I had a draft, send it and she’d show it to her editor. (Cue to slashing wrists because I still don’t have a decent draft and now I don’t have her.) One of the pathetic secrets of my heart.

PS: I still have the emails we exchanged – faded photos of a different kind.

Thank you to Farrar Straus & Giroux for giving me an advance review copy of the book.