What do you think?

Rate this book

672 pages, Hardcover

First published May 15, 2018

The East India Company iron steamship Nemesis, commanded by Lieutenant W. H. Hall, with boats from the Sulphur, Calliope, Larne, and Starling, destroying Chinese war junks in Anson's Bay on 7 January 1841.

The East India Company iron steamship Nemesis, commanded by Lieutenant W. H. Hall, with boats from the Sulphur, Calliope, Larne, and Starling, destroying Chinese war junks in Anson's Bay on 7 January 1841.“The truth of the Chinese empire is that it is inhabited by 350,000,000 of human beings, all directed by the will of one man, all speaking one language, all governed by one code of laws, all professing one religion, all actuated by the same feelings, of national pride and prejudice, tracing back their history not by centuries but by tens of centuries, transmitted to them in regular succession under a patriarchal government without interruption. ...” — Sir James Graham, 2nd Baronet, House of Commons, 7 April 1840. (The British European. population in 1840 was 27 million)Platt describes China’s effort to preserve its status quo amid global Western expansion after the Napoleonic Wars, which was spurred by industrialization and early Victorian evangelical influence. The book is organized chronologically, centered on London, Beijing, Canton (modern Guangzhou), China’s southern coast, and New England, with British India playing a key supporting role. It frames the conflict more as a Clash of Cultures between Christian Imperial Britain and Confucian Imperial China than of empires, with the U.S. and several European powers also participating.

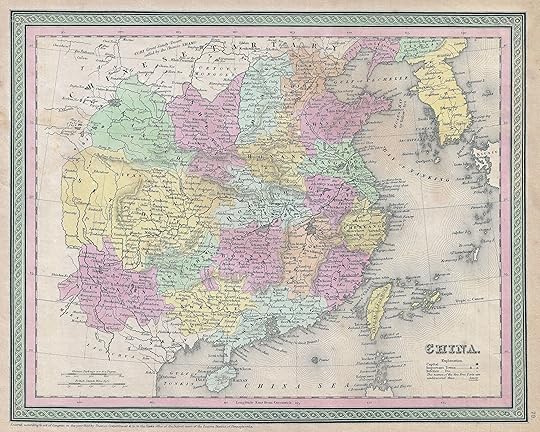

1853 map of China. Canton and Macao appear on the large bay in light-blue Kwangtung province in the lower-center of the map on the China Sea.

1853 map of China. Canton and Macao appear on the large bay in light-blue Kwangtung province in the lower-center of the map on the China Sea.a gigantic planetarium that had taken thirty years to build and was deemed "the most wonderful piece of mechanism ever emanating from human hands." There were giant lenses of every description. There were globes of the stars and earth, two carriages even more ornate than the king’s own (one for the emperor’s use in summer and the other for winter), "chemical and philosophical apparatuses," several brass field guns, a sampling of muskets and swords, howitzer mortars, two "magnificent" lustres (elaborate chandeliers that could illuminate a room) packed in fourteen cases, vases, clocks, an air pump, Wedgwood china, artwork depicting everyday life in England, paintings of military battles on land and sea, portraits of the royal familyas well as a hot-air balloon, all accompanied by a letter from King George III, respectful to the point of fawning ("the Supreme Emperor of China...worthy to live tens of thousands and tens of thousands thousand years"). Alas, none of this made much impression on the Qianlong Emperor:

"As the Greatness and Splendor of the Chinese Empire have spread its Fame far and wide, and as foreign Nations, from a thousand Parts of the World, crowd hither over mountains and Seas, to pay us their Homage, and to bring us the rarest and most precious offerings, what is it that we can want here?" In words that would sting the British for a generation, he added, "Strange and costly objects, sufficient to amuse children, do not interest me...We possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures."Amazingly, this was a feint, directly following the playbook - the millennia-old Book of Documents, which advises "When he does not look on foreign things as precious, foreigners will come to him". In secret the Emperor collected English clocks, wrote poems about telescopes, and advised his courtiers to observe the planetarium's assembly so that they could reproduce it afterwards.

those two terrible trades [opium and slavery] had in common that no matter how abhorrent they were in the eyes of God, even the most respectable of Britain’s trading houses did not hesitate to engage in them.Napoleon, imprisoned on St Helena, mentioned to his Irish doctor that the British should have made more of an effort to respect the customs of the Chinese (in the wake of the failed Amherst mission). The doctor replied that

it didn’t matter if the British had the friendship of the Chinese. They had the Royal Navy.At the time that Britain was considering going to war to defend the opium trade, the future four-time Prime Minister Gladstone (whose sister was an opium addict) gave an impassioned speech against it, saying, "a war more unjust in its origin, more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace, I do not know, and have not read of". In his personal diary he wrote "I am in dread of the judgements of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China". But with the support of Lord Palmerston and the Duke of Wellington, it was prosecuted without much fuss. (Despite the intense debate and general international condemnation of Britain, it is somewhat surprising that there was a second war just fourteen years later, although the book doesn't cover it.)

Napoleon’s eyes turned dark. "It would be the worst thing you have done for a number of years, to go to war with an immense empire like China," he said. "You would doubtless, at first, succeed, but you would teach them their own strength. They would be compelled to adopt measures to defend themselves against you; they would consider, and say, ‘we must try to make ourselves equal to this nation. Why should we suffer a people, so far away, to do as they please to us? We must build ships, we must put guns into them, we must render ourselves equal to them.’ They would get artificers, and ship builders, from France, and America, and even from London; they would build a fleet," he said, "and, in the course of time, defeat you."