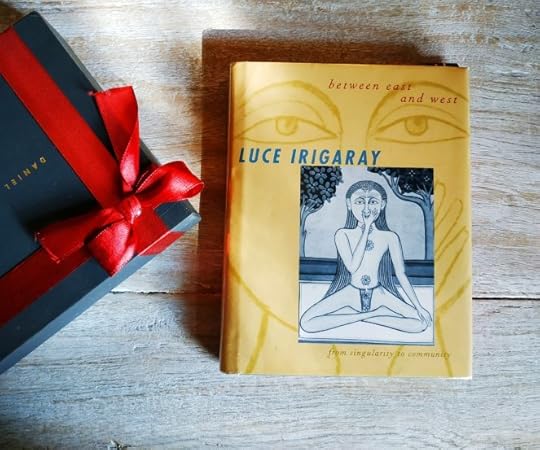

With this book we see a philosopher well steeped in the Western tradition thinking through ancient Eastern disciplines, meditating on what it means to learn to breathe, and urging us all at the dawn of a new century to rediscover indigenous Asian cultures. Yogic tradition, according to Irigaray, can provide an invaluable means for restoring the vital link between the present and eternity―and for re-envisioning the patriarchal traditions of the West.

Western, logocentric rationality tends to abstract the teachings of yoga from its everyday practice―most importantly, from the cultivation of breath. Lacking actual, personal experience with yoga or other Eastern spiritual practices, the Western philosophers who have tried to address Hindu and Buddhist teachings―particularly Schopenhauer―have frequently gone astray. Not so, Luce Irigaray. Incorporating her personal experience with yoga into her provocative philosophical thinking on sexual difference, Irigaray proposes a new way of understanding individuation and community in the contemporary world. She looks toward the indigenous, pre-Aryan cultures of India―which, she argues, have maintained an essentially creative ethic of sexual difference predicated on a respect for life, nature, and the feminine.

Irigaray's focus on breath in this book is a natural outgrowth of the attention that she has given in previous books to the elements―air, water, and fire. By returning to fundamental human experiences―breathing and the fact of sexual difference―she finds a way out of the endless sociologizing abstractions of much contemporary thought to rethink questions of race, ethnicity, and globalization.