What do you think?

Rate this book

432 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2014

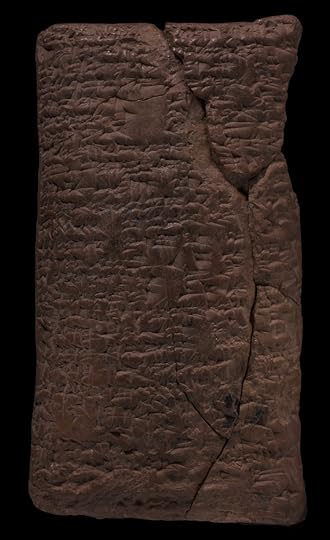

Wall, wall! Reed wall, reed wall!After reading this book, I think I have a pretty good idea of how utterly exciting it must have been for the author when he first laid his eyes upon the above words, written on a small tablet of clay, in cuneiform, the world’s oldest writing system, used in Mesopotamia some 4000 years ago.

Atra-hasîs, pay heed to my advice,

that you may live for ever!

Destroy your house; build a boat; spurn property

and save life!

Scholars and historians like to stress the remoteness of ancient culture, and there is an unspoken consensus that the greater the distance from us in time the scanter the traces of recognisable kinship […]. As a result of this outlook the past comes to confer a sort of ‘cardboardisation’ on our predecessors, whose rigidity increases exponentially in jumps the further back you go in time. As a result the Victorians would seem to have lived exclusively in a flurry about sexual intercourse; the Romans worried all day about toilets and under-floor heating, and the Egyptians walked about in profile with their hands in front of them pondering funerary arrangements, the ultimate men of cardboard. And before all these were the cavemen, grunting or painting, reminiscing wistfully about life back up in the trees. As a result of this tacit process Antiquity, and to some extent all pre-modern time, is led to populate itself with shallow and spineless puppets, denuded of complexity or corruption and all the other characteristics that we take for granted in our fellow man, which we comfortably describe as ‘human’. It is easiest and perhaps also comforting to believe that we, now, are the real human beings, and those who came before us were less advanced, less evolved and very probably less intelligent; they were certainly not individuals whom we would recognise, in different garb, as typical passengers on the bus home.

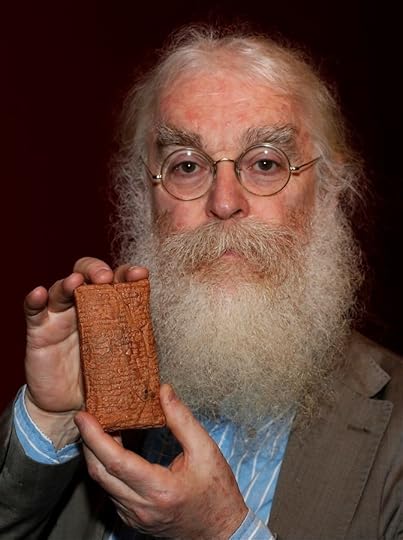

Having finished reading The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Stories of the Flood, it is clearly obvious that author Irving Finkel is the smartest guy in the room. Any room. He has spent a lifetime deciphering ancient Mesopotanian cuneiform, and he is reportedly as comfortable reading ancient Babylonian texts as most modern readers are reading newsprint.

Finkel goes to great lengths with photos and diagrams to explain how he deciphers cuneiform symbols. I tried to follow his meticulous explanations, but it was all Mesopotanian to me.

I expected to find a comparative survey of the flood legends of the various middle eastern cultures. The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Stories of the Flood certainly provides a look at the tradition of the flood from the perspective of a number of different cultures.

My takeaway from this volume is a new appreciation of the knowledge and skill required to bring dead languages to life.

As a kid, I wanted to be an archaeologist. Maybe I still do.

My rating: 7/10, finished 5/4/21 (3533).