British music writer Paul Trynka is a man on a mission, and his mission is to restore the late Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones to what Trynka argues is his proper place in the history of the band. For Trynka, this mission is necessary because over 40 years after Jones' death Mick Jagger and Keith Richards have gradually managed to "airbrush" Jones' role in the making of the Stones from the record, which Trynka describes as "a Stalinesque revision of history." He frequently cites passages from Richards' 2010 autobiography, numerous interviews with Jagger, and other evidence in support of his argument. Trynka couples this evidence with dozens of interviews, seeking at

every turn to identify individuals who might provide first-hand witness to Jones' life without somehow being compromised by some current obligation to the Stones organization.

Trynka's thesis, simply stated, is that Brian Jones was THE essential figure in the forging of the Rolling Stones and its success in bringing rhythm'n'blues music to a much larger mass audience - particularly a younger white audience - than might have been possible otherwise. Jones was a supremely dedicated blues music devotee who spent countless hours mastering the styles he researched on recordings while growing up in the somewhat posh borough of Cheltenham in Gloucestershire, England. Despite a complete lack of support from his family, who frowned on his musical ambitions, and even from his fellow blues enthusiasts, who argued that the music would remain an acquired taste and never find a popular audience, Jones persisted in his vision, spending over three years honing his craft in various musical combos while living in precarious financial circumstances. In 1962 he relocated to London and gravitated to the small but vital rhythm'n'blues community revolving around Alexis Korner's combo Blues Incorporated and impresario/promoter Giorgio Gomelsky's informal and formal blues clubs. There is assembled the musicians who would eventually become the Rolling Stones.

As Trynka argues, Jones' many talents included not only his well-honed musicianship but also his fierce determination, his seemingly effortless ability to cultivate styles and images of the band that were effective in staking out an identity, and his lack of a "purist" sensibility that did not disdain pop music. Throughout his years with the Stones, Jones demonstrated again and again a willingness to try new instruments, new sounds, and new arrangements, and he was constantly curious and willing to learn from other cultures, seeking out traditional musicians in Morocco on several visits. Trynka argues repeatedly that Jones' confidence and authority established him as the undisputed leader of the Stones during at least their first two years as a band.

Nevertheless, as Trynka also details at great length, Jones was also a deeply flawed individual who eventually alienated and repelled many of the people around him, and his weaknesses left him increasingly vulnerable to challenges from Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, who sought to ally himself with Jagger and Richards while encouraging them to write original material for the band, freezing Jones out in the process.

Jones' less appealing qualities included moodiness, misogyny, bouts of cruelty toward those close to him, a lack of reliability and responsibility, narcissism, and an often cloying neediness - there are numerous scenes in the book where Jones begs an ever-smaller number of friends and acquaintances to stay with him at night until he falls asleep because he cannot bear to be alone. Jones also suffered from frequent crises of confidence, and at a critical juncture in 1965 this prevented him from leaving the Stones at a point when the humiliations imposed by his manager and band-mates had reached new lows. Trynka attributes some of Jones' problems, particularly his neediness, to the emotional sterility of his childhood, arguing that Jones was always seeking support and approval, leaving the reader to conclude that much of Jones' more outlandish and outrageous behavior was simply a form of acting out.

Eventually, Jones took to heavy drinking and drug consumption to cope with his marginalization within the Stones and his loneliness and isolation. Trynka describes Jones' two-year relationship with Anita Pallenberg as largely toxic in nature, with a kind of sado-masochistic core that led them to egg each other on to excessive behavior. When Pallenberg abruptly left Jones for Stones guitarist Keith Richards in 1967 during a trip to Morocco, Jones was apparently more dismayed by Richards' betrayal than by Pallenberg's. Jones continued to make modest contributions to Stones recordings, but the last 18 months of his life were mostly miserable, as he was also the subject to drug raids by the British police. He was dismissed by the Stones shortly before their 1969 tour, in part because his drug charges made it unlikely he would be issued required travel visas but also because the Stones had finally rendered him useless as their new musical leaders were finally ready to assume full control of the band's musical direction. Jones drowned in his swimming pool just a few weeks after leaving the Stones.

Is Trynka's argument convincing? Certainly he makes a case for Jones' often contradictory nature, amply documents the demons that plagued him, and makes clear how Jones' focus on music to the exclusion or almost all other considerations, including the important work of cultivating strong relationships within the Stones and taking an interest in its business affairs, proved fatal to his position in the group. Trynka is often persuasive in arguing for Jones' visionary and highly ecumenical approach to music and attempts to make a case for Jones as an early advocate for what we today call "world music" (with recordings he arranged during a 1968 trip to Morocco eventually being released in 1971 as "Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka"). He is also unsparing in his accounts of Jones' less appealing qualities, describing how Jones had fathered four children with four different women by the age of 19 but took little or no interest in, and no responsibility for, any of them.

One could also argue the continuities that enable us to speak of the "Rolling Stones" as a single entity over a period of 53 years may be very misleading. Perhaps there was the band as Jones made it, and the one that succeeded him, or a few other subdivisions? But there remain echoes of Jones even in the most recent Stones album, a collection of blues covers that Jones would have had no trouble recognizing or playing on. Despite its blatantly partisan tone, Trynka's book does offer a compelling case for the significance of Jones' leading contributions to rock'n'roll in the 1960s and his lasting impact. A good read, even if you want to argue with it.

~12:30

~12:30

He died in a pool right next to a Hundred Acre Wood

He died in a pool right next to a Hundred Acre Wood

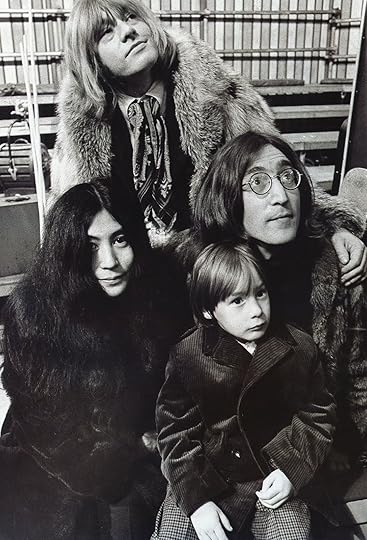

Brian Jones with Donovan, Ringo, John, Cilla Black, Paul and the band Grapefruit (seated) at Grapefruit's single launch party, 1968

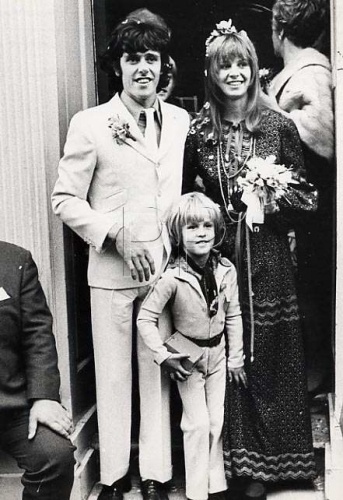

Brian Jones with Donovan, Ringo, John, Cilla Black, Paul and the band Grapefruit (seated) at Grapefruit's single launch party, 1968  Donovan & Linda Lawrence with her son Julian (her child with Brian Jones)

Donovan & Linda Lawrence with her son Julian (her child with Brian Jones)